Sister Soldier: The Story of Victoria Davis

An off-duty police officer killed her brother. Now she's gone from fear to fighting back.

TheGrio has launched a special series called #BlackonBlue to examine the relationship between law enforcement and African-Americans. Our reporters and videographers will investigate police brutality and corruption while also exploring local and national efforts to improve policing in our communities. Join the conversation or share your own story using the hashtag #BlackonBlue.

Victoria Davis sold her car. The logic was that if she wasn’t driving it a police officer wouldn’t be able to pull her over. No car on the road meant she wouldn’t end up harassed, dead or the reason for another hashtag.

“I put myself in a position where I didn’t have to interact with them at all,” says Davis, two years after her older brother, Delrawn Small, was killed by an NYPD officer.

After all, it did start with a car.

Small, 37, was driving with his girlfriend, infant son, and one of his teenage daughters after a family cookout the evening of July 4, 2016, when they encountered off-duty police officer, Wayne Isaacs, on the road.

The story goes that Isaacs cut Small off on a busy stretch of road on Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn, NY. Small followed him to the next red light, then approached Isaacs’ car to confront him. Within seconds, Small was shot dead.

The shooting happened the same week Philando Castile and Alton Sterling were killed by police officers: Philando Castile on July 5th, Alton Sterling on July 6th. Small was one of 957 people killed by police that year. But you probably don’t know his name.

“He didn’t seem like the perfect police killing victim,” says Davis about her brother.

Delrawn Small poses with his infant son. (Family photo)

Initial media reports labeled it a “road rage” incident, repeating NYPD’s and a witness’ claim that Small approached Isaacs car and punched the off-duty officer, threatening to kill him, so Isaacs shot him in self defense. Small’s past arrest record was published and he was referred to as an “ex-con” in one news report.

When Davis, 34, heard the news about her brother, she didn’t believe it. Harsh online comments about him brought her to tears. She was a city public health worker and mother to a 7-year-old boy, Carmelo. Davis had survived foster care and her mother’s death as a teen, but now she couldn’t cope.

“When Delrawn was first killed, I felt so defeated. I couldn’t talk. I was battling depression, anxiety,” recalls Davis.

The day would come, however, when Davis would have to find her voice again, not just for her brother Delrawn, but to speak for other black men and women who would later die at the hands of police.

Before that day would come, Davis would embark on the tumultuous journey of moving from sister to spokesperson.

“I went from being Delrawn’s sister to being Delrawn’s mother and grandmother to [his] kids almost. People were holding me accountable for all types of things,” says Davis.

“I remember telling my family, ‘I am just a sister.’ I even said, ‘I didn’t kill Delrawn, I didn’t do it. I’m fighting for Delrawn.'”

Collateral Damage

It’s a story that’s common for Black families whose loved ones become victims of police brutality and shootings. Overnight they are thrusted into the spotlight, invited to speak on national television, testify in hearings, manage GoFundMe accounts, and become advocates for their deceased loved ones.

Sybrina Fulton and Tracy Martin, parents of Trayvon Martin, Lezley McSpadden, mother of Michael Brown, Gwen Carr, mother of Eric Garner, and Nicole Paultre-Bell, former fiancé of Sean Bell all know too well what Davis has been through. They willingly let go of their privacy to become recognizable faces of this movement with some joining speakers bureaus, endorsing political candidates, writing books and creating foundations in the name of their loved ones.

But how does one mourn a loved one’s death, while holding steady at center stage? And when does responsibility become a burden too heavy to bear?

Erica Garner, the daughter of Eric Garner, died at 27 of a heart attack last year. At her funeral, tensions reportedly escalated after her grandmother (Gwen Carr) alleged that she was not allowed to attend.

“These police killings cause a lot of problems with families,” says Davis.

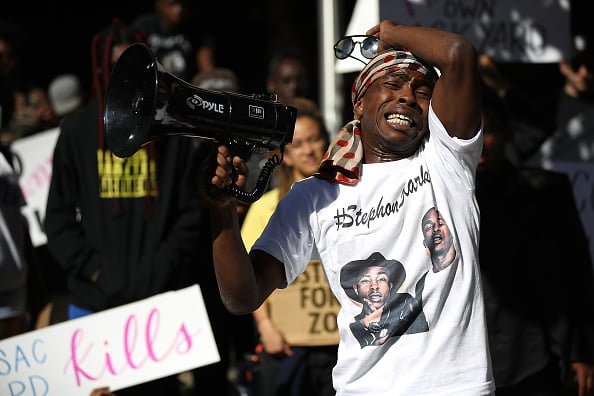

SACRAMENTO, CA – MARCH 28: Stevante Clark, brother of Stephon Clark, speaks during a Black Lives Matter protest outside of office of Sacramento district attorney Anne Schubert on March 28, 2018 in Sacramento, California. (Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

Stevante Clark, the brother of Stephon Clark slain by Sacramento Police in March, garnered national attention for his public outbursts of grief. He interrupted Sacramento Mayor Darrell Steinberg at a city council meeting, took the mic from a speaker at his brother’s funeral, and demanded CNN anchor Don Lemon say his brother’s name during a live interview.

Online commentators were harsh and judgmental– “He’s a jacka** & is literally profiting off his brothers death,” wrote one Instagram user. “Fake. It’s all about attention for himself,” wrote another.

“People expect us to grieve, but not be too happy- but not be too sad either,” says Davis, who says she called Stevante to offer support after his brother’s death. “I’m pretty sure some of my behaviors didn’t look like Victoria. It’s a lot.”

A Reason to Fight

Right when Victoria Davis was feeling the weight of her brother’s death, a flicker of hope would come.

Four days after the shooting, a surveillance video was released, showing Delrawn Small had been shot within seconds of approaching Wayne Isaacs’s car, putting into question Isaacs’s claim that Small punched him.

New headlines went up, this time telling a different side of the story. Within weeks the New York Attorney General’s Office got involved, declaring it would prosecute Wayne Isaacs for murder and manslaughter. Isaacs would become the first police officer in the state to be prosecuted under an executive order signed by Gov. Andrew Cuomo, after the death of Eric Garner.

If found guilty, Isaacs, 37, a Guyanese-born immigrant, would have faced life in prison.

(Victoria Davis was featured in an episode of “True Story” back in 2017 before the trial of Wayne Isaacs)

His lawyers insisted the police officer did nothing wrong and they would fight fiercely on his behalf.

Davis wanted to help put Wayne Isaacs behind bars, but would people truly listen to her?

In search of answers, she went to a memorial for Kimani Gray, another teen killed by police. She ended up standing next to Natasha Duncan, whose unarmed sister, Shantel Davis, was killed by a plain clothes NYPD officer in 2012 after a car accident.

Davis opened up and began pouring her heart out to the stranger.

“I was telling her I’m so sad and I don’t know what to do- and I’m just a sister. I don’t know if anyone knows what it’s like,” says Davis. Duncan encouraged her to fight back. “Being around other families and seeing how they did things, I was like, ‘I can do this. I can speak for Delrawn.’ It gave me more endurance,” says Davis.

Davis teamed up with her surviving brother, Victor Dempsey, and local grassroots organization, the Justice Committee, which advocates for police accountability and supports family members who lost loved ones at the hands of police. The siblings fueled their anger into advocacy, spending the next year creating social media campaigns, leading marches, memorials and protests in their brother’s name.

The Verdict

When Wayne Isaacs’s trial began in November 2017, he testified that Delrawn Small punched him and threatened to kill him at the stop light that night. Issacs said he didn’t feel safe enough to drive away, according to The New York Times.

After three days of deliberation, a jury found Isaacs not guilty of any charges in the shooting death of Delrawn Small.

Brooklyn Supreme Court Justice Alexander Jeong said to Isaacs, “Only you know what exactly happened out there. So, no one’s passing any judgment, and let’s try to hope that we have no further incidents like this in the future.”

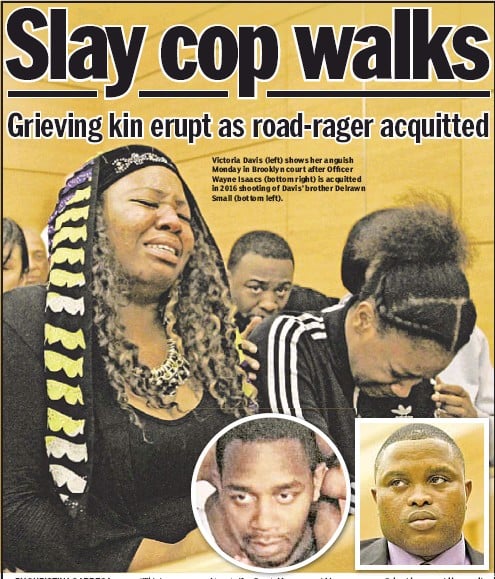

(New York Daily News: The cover of the New York Daily News featured Victoria’s reaction to the Wayne Isaacs’ verdict.)

Davis’ agonized face in reaction to the verdict made the front page of the New York Daily News. It was becoming an all too familiar image. Yet another Black woman in pain, who’d lost a brother, son, father or partner in an encounter with law enforcement.

Isaacs has since returned to work on desk duty.

“That verdict…it did damage to her,” says Davis’ brother, Victor Dempsey, reflecting back on that day. “It was like witnessing our brother die for a second time.”

Even with the agonizing reality that her brother’s killer was found innocent of all charges, Davis wouldn’t stay down for long though.

“I think that pain lit a fire in her,” says Dempsey. “This enraged her so much it helped her concentrate the pain.”

Four months after the verdict, Davis hopped on a flight to the inaugural Power Rising Summit in Atlanta, a conference that promised to help black women politically organize and network with each other. She wanted to run into one person: First Lady of New York, Chirlane McCray.

Davis rehearsed the words she would say to McCray about the Isaacs’ verdict and his return to work as an NYPD officer. Essentially, both Davis and Issacs were employed by the City of New York under Mayor Bill de Blasio.

“How does he get to go about his life? I’m a city worker just like him and I have no infractions yet he’s a murderer and he’s back on the job?” Davis questioned in her conversation with McCray. “Is he more important than I am?”

A protestor holds a sign at a Father’s Day rally in honor of people who died at the hands of police. (theGrio/Natasha S. Alford)

Finding Her Voice

As the two-year anniversary of Small’s death approaches next week, Davis is going all out in her campaign to get Isaacs fired, using social media as her platform and circulating the hashtag #FireWayneIsaacs. Both Davis and her brother recently presented a letter to Mayor de Blasio requesting a meeting about Isaacs and his continued role with the department.

The once shy and soft-spoken sister now gives fiery speeches. In fact, she recently spoke on a “How Can We Stop The Violence?” panel in April hosted by Gwen Carr and other Mothers of the Movement.

A crowd of about 20 people, scattered around the room in foldable chairs, nodded their head, listening intently to her every word. Victoria Davis had them hooked.

Victoria Davis rallies on the steps of City Hall for a Father’s Day press conference put on by surviving families of police shootings. (theGrio/Natasha S. Alford)

“My fight is to change narratives around Black people as a whole. I am a mother and I have a Black son. Our melanin is treated like it’s a weapon and it’s not,” said Davis at the podium.

“My message is to continue to uplift Black people because we don’t know if we’re going to be safe. We don’t know if we’re going to make it home at night. We don’t know if we’re going to make it to tomorrow because we have so many cards stacked against us,” said Davis. “But we’re resilient people, we’re powerful people.”

The room erupted in applause and Davis walked back to her seat to sit next to her son, Carmelo, who waited patiently for his mom while playing games on an iPhone.

Davis has also been accepted to the Community Organizer Apprenticeship, a rigorous 10-month program at The Center for Neighborhood Leadership (CNL) where she’ll get paid to use her new skills as an activist and organizer. She interviewed for months to earn the spot.

And Davis finally got another car. Her packed schedule demanded it.

Victoria Davis speaks at a rally with her son, Carmelo, 7, by her side. (Courtesy Photo)

“As far as attending rallies, she’s everywhere,” says Dempsey. “She sniffs out anything that’s political. Her drive and passion now exudes what I think of as a sister— what my sister was able to do is superhero status. She’s raised the bar.”

Davis counts therapy and group counseling as the guiding forces that saved her from depression, a topic she wants to destigmatize in the Black community.

“Sometimes I feel like I don’t know who that person was at his death,” Davis says, recalling her early struggles after the shooting. “I was becoming a martyr for the movement for Delrawn, almost like I would die for this,” she says of her mindset after the trial.

“I took a step back in December and was like, ‘No I don’t want to die for this. I want to live for this. I want to live to see change. I want to live to see justice. And what does that really look like?”

A Reason To Live

New life and change would come at the start of 2018 in Davis’ personal life too.

Victoria is expecting her second child. A boy.

“People were like, maybe you shouldn’t have it,” says Davis.

“It wasn’t an option for me. What I felt was maybe God was like, we’re gonna get this girl to focus on something other than grieving… Have her focus on giving life instead of this death.”

Victoria Davis poses on the steps of City Hall after speaking at a rally for police reform June 18, 2018. (theGrio/Natasha S. Alford)

Davis’ son is due on October 22, 2018 or O22— the National Anti-Police Brutality Day. When people asked whether she would stop protesting after having the baby, Davis responded with a laugh:

“I was like ‘I’m gonna protest!’ I’m gonna strap the one with my chest and walk with the other.”

Defying expectations once more, Victoria Davis has decided not to name her son after her brother Delrawn.

Instead, she says his name will represent the force that keeps her fighting every day.

“Justice. His name will be Justice.”