By EDDIE PELLS AP National Writer

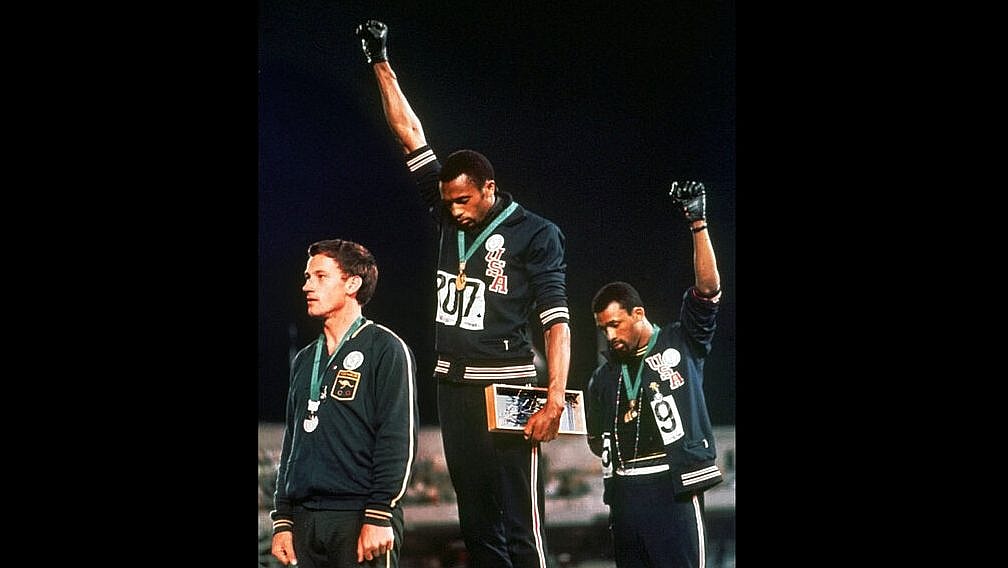

More than a half-century later, Tommie Smith and John Carlos are cemented into Olympic lore — their names enshrined in the Olympic Hall of Fame in the United States, their portrait an indelible fixture on the universal sports landscape.

As for that raised-fist salute that transformed them into Olympic icons, while also symbolizing the power athletes possess for the short time they’re on their biggest stage — it’s still forbidden.

Such was the warning this month in the announcement by the IOC, whose athletes’ commission banned kneeling and hand gestures during medals ceremonies and competiton. It’s all part of an attempt to tamp down political demonstrations at this summer’s Tokyo Games.

“The eyes of the world will be on the athletes and the Olympic Games,” IOC President Thomas Bach said, in delivering an impassioned defense of the rules.

IOC athlete’s rep Kirsty Coventry portrayed the guidance as a way to provide some clarity on an issue that has confounded both athletes and authorities for decades.

The issue, always bubbling, surfaced last year when two U.S. athletes — Gwen Berry and Race Imboden — used medal ceremonies to make political statements at the Pan American Games. Those gestures brought a strong rebuke from the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic committees, but the groups still appear confused and conflicted about the entire matter.

(The USOPC didn’t welcome Smith and Carlos to an officially sanctioned event until 2016. )

The IOC got its atheltes’ commission, which has often contradicted key athlete movements in other Olympic areas, to get out front on the issue and offer its advice. It was essentially no different from what the IOC itself has been touting for years. Not surprisingly, some view it as an out-of-touch, retrograde attempt to stifle an increasingly outspoken generation of athletes.

The mushrooming of live TV, to say nothing of the outlets now available on social media, has empowered athletes — the best examples from recent years would be Colin Kaepernick and Megan Rapinoe, but there are dozens more — to use sports to send a message.

Rapinoe’s reaction to the IOC announcement: “We will not be silenced.” As much as her play, Rapinoe’s outspoken fight for equal pay for the U.S. women’s soccer team underscored the American victory in the World Cup last year and made her, in the minds of many, the most influential athlete of 2019.

“So much for being done about the protests,” Rapinoe wrote on Instagram last weekend. “So little being done about what we are protesting about.”

The athletes’ commission said disciplinary action would be taken “on a case-by-case basis as necessary” and listed the IOC, the sports federations and the athletes’ national governing bodies as those who will have authority to make the call. It made no mention of what the sanctions could be. In that respect, it added confusion, and might have served to emphasize the power disparity between the athletes, who are the show, and the agencies who run this multibillion-dollar enterprise and, for all intents and purposes, control the invitation list.

Among the other questions not answered in the guidance document:

Who, exactly, will adjudicate the individual cases and how will cases be adjudicated?

Who, exactly, will have ultimate responsibility for implementing sanctions?

While those questions went unanswered, the document did include the reminder that “it is a fundamental principle that sport is neutral and must be separate from political, religious or any other type of interference.”

That concept, however, runs counter to long thread of Olympics-as-politics storylines that have dominated the movement since it was founded in 1896.

A truncated list includes:

—Hitler’s hosting of the 1936 Games (winter and summer) in Nazi Germany.

—IOC President Avery Brundage’s ham-handed handling of South Africa’s status in the Olympics during apartheid.

—The 1972 massacre of Israeli athletes during the Munich Games.

—The U.S. boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympics, followed by the Soviet Union’s boycott of the 1984 Los Angeles Games.

—The IOC’s awarding of the 2008 Olympics to Beijing, in part compelled by promises to shine a light on the country’s attempt to improve human rights.

More recently, Bach has found the committee a permanent place at the United Nations, used the Pyeongchang Games in South Korea to strive for better relations between the Koreas and spent ample time negotiating deals with leaders who have been kind enough to spend billions to stage the Olympics.

Though the IOC would argue that there are still places to make political statements in the Olympic space — news conferences and social media among them — it does not condone them on the field of play or the medals stand. It made all the more striking the picture the IOC tweeted out last Monday: Bach posing on a mountain with athletes in uniform from the United States and Iran at the Youth Olympic Games — a political statement during a time of strife that is designed to forward the long-held IOC-driven credo that the Olympics promote peace.

Peace itself is dependent on politics, and the people who run the Olympics are well connected to that world.

No fewer than nine members of IOC itself are princes, princesses, dukes or sheiks — and that list doesn’t include the multitude of government officials involved in organizations that branch out of the IOC. For instance, half the World Anti-Doping Agency’s board comes from governments across the globe.

Bach has singled out political concerns as a major divider in the Russian doping scandal that has embroiled the Olympics the past five years — implying it’s as much an East vs. West issue as one based on decisions that stem from painstakingly accumulated evidence.

The latest move comes in the run-up to what figures to be a divisive election year in the United States, the country that sends the largest contingent to the Olympics, wins the most medals and often lands some of the most outspoken athletes on the podium.

Smith and Carlos were booted from Mexico City after their protest. If history — to say nothing of Rapinoe’s reaction — is any guide, the IOC could be placed in the position to decide whether to make that same sort of statement again.