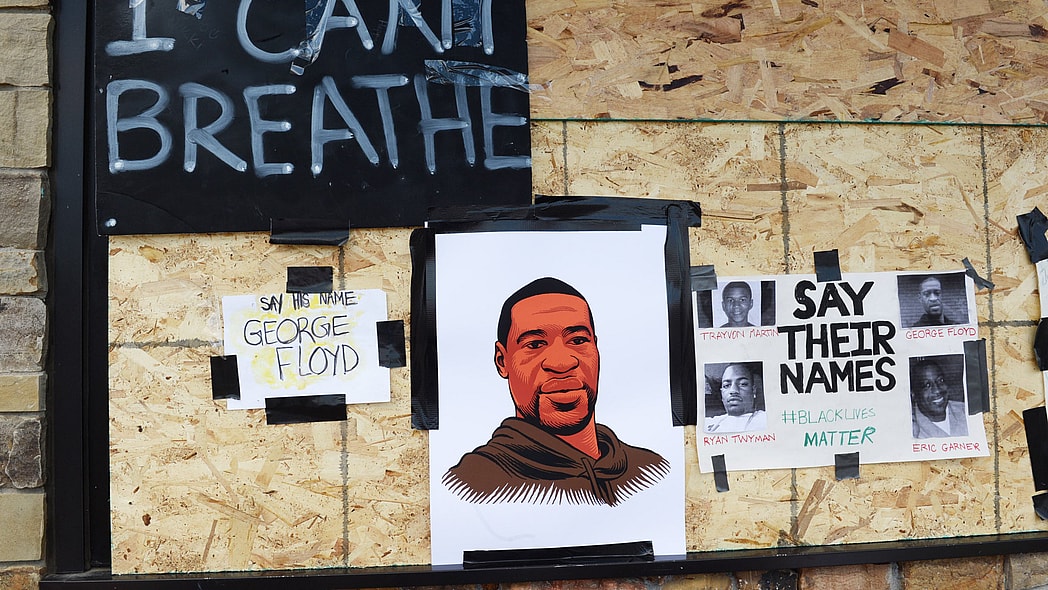

Shortly after George Floyd took his last breath, Mayor Jacob Frey likely made a call to Minneapolis Chief Financial Officer Mark Ruff to ask a surprisingly pointed question: “Can we afford this?”

In 2019, Minneapolis settled a wrongful death suit with the family of Justine Damond for an unprecedented $20 million for her fatal encounter with the Minneapolis Police Department.

No previous settlement for a civil rights suit had even come close — local activists complained that this was because Justine was white and other victims of police killings, like Jamar Clark, were Black.

READ MORE: No discipline for cops in killing of Minneapolis man Jamar Clark

The payout blew a hole in the city’s “self-insurance” (an industry term for no insurance) fund, leaving less than $10 million dollars to cover future liabilities. At the time, Ruff and the city’s actuaries believed additional seismic settlements were unlikely, in spite of the police department’s history of brutality.

Then, officer Derek Chauvin murdered George Floyd.

As Americans, exasperated and enraged by yet another murder of an unarmed Black man at the hands of police take to the streets, many are asking what more they can do to assure this never happens again. For some, it may be as simple as changing insurance providers.

Insurance plays a shocking role in achieving justice for victims of police brutality. When an officer kills a civilian, neither the officer nor the police department actually foot the bill. That payout falls on the coffers of the city employing the officer.

READ MORE: Benjamin Crump: Floyd family to file civil suit against killer cop Derek Chauvin

For example, in spite of the well-publicized settlement New York City reached with the family of Eric Garner, Daniel Pantaleo — the NYPD officer who choked Garner to death in 2014 — never personally compensated the Garner family. The residents of New York City paid.

And former officer Chauvin, who knelt on Floyd’s neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds, will likely never pay the Floyd family a penny — even if found guilty of third-degree murder or manslaughter. That responsibility, again, will fall on Minneapolis — or its insurer.

Indeed, one of my first assignments as a new civil rights lawyer was to reach out to our insurance counsel to determine the extent of the defendant’s coverage. I wanted to focus on the officers and their misconduct. But the defendant, a southern city, had changed carriers since their officers fabricated evidence that cost our client over two decades of his life.

The firm was understandably concerned: the value of the suit would be in doubt if the coverage had lapsed. And I learned immediately that less coverage meant millions less for a man who had suffered unimaginably, wrongfully convicted for a crime he did not commit.

READ MORE: Three Baltimore men to receive $8.7 million for wrongful convictions

Like probably most Americans, I was initially appalled at the financialization of police brutality. It’s sickening to think that insurance companies are in the business of covering officers for their acts of brutality. Yet, insurers have played a role in indemnifying cities and officers since at least the 1960s and even more so in recent years.

According to Travelers Insurance, the nation’s second-largest writer of U.S. commercial property-casualty insurance, ‘Law Enforcement Liability Insurance’ includes coverage for any “violation of civil rights under any federal, state or local law.”

This includes violations of a citizen’s essential rights under the Constitution. So, if a police officer were to search your car without a warrant; or stop you without probable cause; or brutalize you to the point of death — like George Floyd and so many others — Travelers and other insurers tell cities: We’ve got you covered.

But I now believe spotlighting insurance companies may advance civil rights for victims and those most vulnerable to violent police interactions. Brutality and wrongful death cases have become so pervasive even insurers are championing reforms in order to guarantee coverage.

The logic is simple: fewer victims of police brutality, fewer payouts to covered cities. Because of this, “insurers may be better positioned than government to reform police behavior,” Law Professor John Rappaport argued in a 2017 Harvard Law Review article.

There are already some public examples of insurance companies engaging in police oversight. In 2018, The Atlantic reported that in Wisconsin, an insurer recommended new training and supervision of SWAT teams after two botched drug raids. In 2010, a police chief in Rutledge, Tennessee, was fired to appease the town’s liability insurer after allegations of assault.

These examples have led Freddie Gray’s lawyer, William Murphy, to lobby Baltimore to purchase liability insurance to pay for police misconduct. He hopes that, once the insurers have their hooks in the city’s budget, they can prevent the “rough ride” that took Gray’s life.

There are still very good questions to be asked about whether indemnifying officers encourages police brutality. But there is a way to channel those suspicions and rage against police misconduct: Rather than waiting for insurers to take charge and force change, perhaps it is time for ordinary citizens to demand insurers join the fight to end police brutality by canceling their individual home insurance and auto policies with insurers like Travelers, which underwrite police misconduct.

Advocates alike should launch a nationwide campaign to pressure investors to divest from insurers that won’t mandate reforms or stop insuring police departments that commit constitutional violations.

Increasingly, the Black Lives Matter movement is calling for the abolition of the police. For example, MPD150, a participatory, horizontally-organized effort by local organizers, researchers, artists and activists in Minneapolis, has recommended “a shared vision of a police-free future.”

To some, abolition is considered a radical demand. But it may not be as far-fetched if the goal is to shutter the nation’s worst police departments. According to Rappaport, in the 1980s, a number of municipalities shut their police forces down entirely rather than operate without insurance.

In recent years, Maywood, California and Sorrento, Louisiana, disbanded their police departments after losing insurance coverage. Cities and towns in Illinois, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee have done the same. Without insurance, some cities will not tolerate even the possibility of police misconduct.

When Rodney King was brutally assaulted by four police officers, insurers claimed that the incident “caused concerns in every jurisdiction over liability exposures.” But nearly 30 years later, young Black and brown men continue to be routinely brutalized and murdered by insured police departments and those policies are regularly renewed.

Public pressure may, therefore, be the impetus needed for insurers to build police reform into their values statement and business models.

The threat of withdrawing insurance coverage will not cure the plague of police violence in every instance. Like Minneapolis, large cities including New York City and Chicago tend to self-insure. And though Chicago has paid over $700 million and New York City over $1.1 billion to victims of police misconduct in the last decade, revelations that cities are subsidizing police brutality with taxpayer money has not mobiPreview (opens in a new tab)lized reform.

But smaller departments are more representative of the nearly 18,000 police departments in America. And while New York City, with an annual budget exceeding $80 billion per year, may be able to absorb the costs of its officer misconduct, small towns are not so nimble and many are already insuring their liabilities for police misconduct.

In 2015, former Washington Post reporter Abby Phillips reported that denial of coverage by one of the preferred insurers forced the City of Inkster, Michigan, a town of about 25,000, to raise taxes $179 per household to pay for just a $1.4 million police brutality settlement.

What were the citizens paying for: a white Inkster police officer had dragged Floyd Dent out of his vehicle, put him in an apparent chokehold, punched him repeatedly in the head and used a stun gun — all during a “routine traffic stop.”

If citizens push insurers to require reforms, small and medium-sized cities like Inkster may be forced to ask themselves: is the cost of brutality really worth it?

And reforms in smaller cities may then benefit reform movements in larger cities. This year, New York City will have to cut its budget by nearly $8.7 billion. In an age of austerity and an energized protest movement, big-city mayors may no longer have tolerance for bad officers or systemic racism.

In 2016, activists tried to push a ballot initiative that would have required individual officers to carry liability insurance. But a majority of the Minneapolis City Council voted against putting the amendment on the ballot. The Minnesota Supreme Court affirmed, holding that the city had to insure its officers. That defeat may turn out to be an opportunity.

A $20 million self-insured obligation may finally force Minneapolis to insure against its liabilities for police brutality.

For Americans looking for a proactive response to what they see playing out in streets all over the country, calling insurers to ask if they or their affiliates provide coverage for any “violation of civil rights under any federal, state or local law” might be the start of a new wave of change that could result in the sort of outcomes protestors are demanding in American streets.

After all, no one should want their home insurance premiums covering the cost of George Floyd’s murder.

Rakim Brooks is an attorney at Susman Godfrey with an interest civil rights law and anti-poverty policy. He graduated from Yale Law School, the Yale School of Management, and Oxford University where he was a Rhodes Scholar. He grew up in Wagner Public Houses in East Harlem neighborhood of New York City.

Rakim Brooks is an attorney at Susman Godfrey with an interest civil rights law and anti-poverty policy. He graduated from Yale Law School, the Yale School of Management, and Oxford University where he was a Rhodes Scholar. He grew up in Wagner Public Houses in East Harlem neighborhood of New York City.

Have you subscribed to theGrio’s podcast “Dear Culture”? Download our newest episodes now!

https://open.spotify.com/episode/7EqV56xsXcxMaCQhYDdQhc?t=0

https://open.spotify.com/episode/71nhtCniY10lItS1qwhmlt