The Cabaret

In artistic Montmartre, Paris, a stone’s throw away from the red windmill tower of the landmark Moulin Rouge, sits a piece of Josephine Baker’s legacy that is not widely known, but for which, a quiet war was waged and lost.

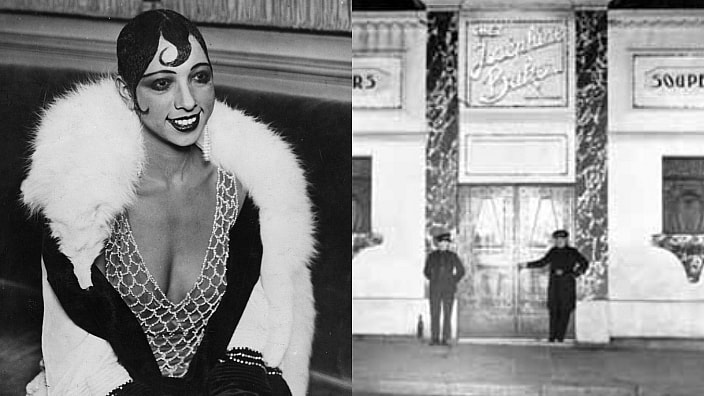

A year after sailing to France to perform in the Revue Nègre at the Champs-Elysees theater, a role that would introduce her to Paris and set her on her way to stardom, Baker opened her own cabaret, Chez Josephine, on Dec. 14, 1926. The cabaret was located on a hillside street in the 9th arrondissement of Paris.

The cabaret was a venture with her business manager and lover at the time, an Italian gigolo and self-declared count, Pepito Abatino.

The nightclub opened to much fanfare, with Baker being the toast of the town.

According to the book “Josephine Baker in Art and Life: The Icon and The Image” by sociology professor Jules Rosette, Baker would often make a grand entrance at midnight after her earlier performances at larger musical halls.

Baker, flamboyantly dressed in flowing gowns and sparkling jewels, would saunter through the club.

In her memoir, “Les Memoires De Josephine Baker,” which was composed in the cabaret with writer Marcel Sauvage, Baker described the club as a place of joy.

Read More: Paula Patton to produce and star in new Josephine Baker biopic

“I’ve never been so amused. I make jokes, I caress the skin of bald men, I play with the beards of bearded gentlemen. Look at these gentlemen in the day: they don’t laugh as much,” she wrote.

“Everyone doing the Charleston, I keep them all entertained, the waiters, the cook, the cashier, the hunters, the goat, and the pig … And me, I dance, I dance.”

Baker’s son Jean-Claude Bouillon Baker, who was adopted along with his 11 siblings who were known as the ‘rainbow tribe,’ said while his mother didn’t speak much about her earlier life, he heard about the cabaret from family.

“I always heard it was an idea of Abatino Pepito because Bricktop Smith had a cabaret in Montmartre. Bricktop gave the example to Josephine Baker on how to start a club in Montmartre to animate the evenings of Pigalle and Montmartre and at the same time to introduce the Charleston into Paris,” he told theGrio.

“So it was a very important place with love and energy and festivity. There were several personalities that came to her cabaret, all of Paris, these surrealist artists, and clearly all the Americans who were traveling tourists. And her very dear friend Sidney Bechet,” Bouillon Baker continued.

Other celebrities often frequented the cabaret. Noted actress Edith Piaf and poet Jean Cocteau were among the guests to appear at the cabaret which Baker operated until 1928.

Chez Josephine was also significant for its connection to the African American community and its early jazz roots in Paris.

French historian and professor Tyler Stovall in his book “Paris Noir,” notes that Baker’s club was instantly popular “welcoming members of both the African American community and the doyens of Parisian nightlife.”

Paris then was much different than the United States as Black people did not experience the same level of racism as they would in the U.S. And the area which housed the cabaret was special for many African Americans who stayed in Paris after World War I.

“For Black people [Montmartre] had significance. First and foremost, it was a place where Black musicians could get jobs, where they could get jobs playing jazz in nightclubs and there was a great demand for them,” said Stovall in an interview. “But it was also a place where it was kind of the first real African American community in Paris.”

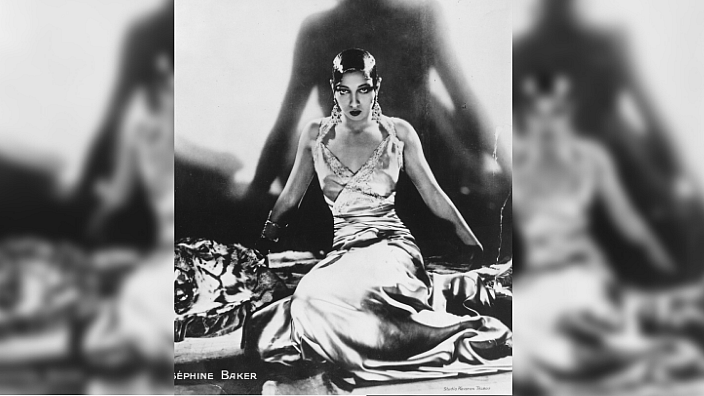

Josephine Baker

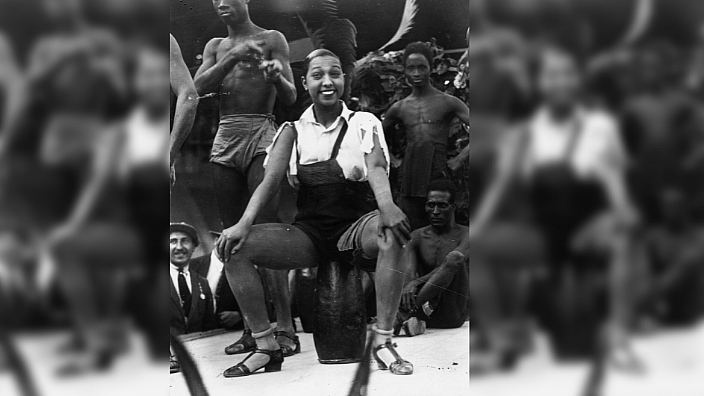

Before reaching dazzling heights as the first modern Black global superstar, Baker was born in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1906. She grew up in stifling poverty cleaning the houses of wealthy white families from the age of 8. Baker entertained audiences on the street before her talent was spotted by a touring company.

She would start performing on tour at the age of 16, and her first major break arrived a year later in the legendary African American produced Broadway-vaudeville play Shuffle Along and another comedy Chocolate Dandies, before moving to Paris in 1925.

Baker also fought for causes she believed in.

According to research by Mary L. Dudziak, when France declared war on Germany in 1939, Baker utilized her connections in the Italian embassy to do intelligence work for the Allies. She joined the Resistance and used her performance tours in Europe to transmit information about “Axis troop movements to the Allies” by writing notes in invisible ink on her musical sheets and passing them on to her handlers.

For her spying, Baker was awarded the Cross of Lorraine by the leader of the French Resistance, Charles de Gaulle in 1943, and in 1961 she became the first American woman to be awarded the Croix de Guerre and the Legion of Honor.

In the U.S., Baker experienced racism as a performer. She was a loud voice for civil rights, and her speech at the March on Washington in 1963 was one of the most memorable moments of her civil rights activism. In the early 1950s, Baker pushed to ensure her U.S. performances were integrated. Her passion for civil rights led the U.S. government to monitor her movements and cancel some of her performances in Latin America. Baker, who identified as bisexual, is also celebrated as an LGBTQ icon.

While Baker is broadly celebrated, there a more accolades that are not as widely known. She was among the first Black women in early 20th century France to have her name on a business that was operated in her likeness and image. At the time as a foreigner, the achievement was phenomenal. It came 18 years before French women were allowed to vote and 45 years after women in France were allowed to open bank accounts.

The aftermath

Chez Josephine is now a trendy bar named Le Carrousel. Its main customers are millennials who reside in Montmartre. On the weekends, hundreds of Parisians and tourists pour into the nightclub for music, cocktails, and dancing.

However, before Le Carrousel was opened in late 2017, Brian Bagley, an African American who moved to Paris more than ten years ago, discovered the building he believed was a critical part of French history; was becoming a bar. It was a travesty, he thought, that the first place in the world to feature Baker’s name would no longer be a symbol of her legacy.

Bagley, a cabaret performer himself, worked at the building briefly between 2015 and 2017 as an artistic director for nightly shows. He grew up in Baltimore and moved to Paris to learn more about Baker, a figure who influences him. He performs as Baker occasionally and became known to her family through his work.

“I was in Italy, the island called Ischia, with a gospel workshop. I was walking down the street when I got a call from one of the dancers: ‘Brian, they’re closing the place,’” Bagley told theGrio.

Bagley said he immediately called people he knew in the industry to halt the sale. He thought the fact that Josephine Baker once had a business there would be enough. Perhaps the building could be preserved for its history and be made into a museum and a cabaret.

“We got Marie Antoinette’s prison, but we don’t have the first cabaret that was opened up by Josephine Baker, really? I see that we can go to Frida Kahlo’s house. I see we can go to [Salvador] Dali’s house. The thing is that those projects are very important,” he said.

One of the people who Bagley reached out to was Bouillon Baker.

He also started a petition on Change.org to pressure the French authorities to stop the sale. The petition: “Saving Black and LGBT History In Paris at Josephine Baker’s First Cabaret Chez Joséphine,” received 354 supporters. The petition read: “We are therefore very worried about what could happen in the short and medium-term on this site and we draw your attention to do your utmost to safeguard this element of French heritage which must not be delivered or sold to buyers who have no regard for its historical value who want to destroy a history that should be preserved!”

The petition and Bagley’s quest to save the building were unsuccessful.

In addition to the petition, Bagley appealed to the Paris City Council, but to no avail. The building was sold to businessman Thibaud Harle and his partners.

Harle acknowledges the controversy surrounding the sale, but said he and his team understand the history the building holds.

“I was very quickly aware through the internet, the name of Le Carrousel came out in one of my Google searches. I was surprised since the petition was untrue, we were not planning on ‘opening another soulless sports bar.’ On the contrary, we did all we could to restore this place identically to what it used to be. We first took this petition very seriously and as we noticed it was not growing in size we let the situation unroll. And I believe it was a good decision,” he said in an emailed response.

“Brian Scott Bagley, who was at the initiative of this petition came to visit us, he saw the building work we had started and the mindset we were in. We are in good terms with him and we stand by our decision to stir Le Carrousel according to the vision Josephine Baker had for it,” Harle wrote.

The businessman and his team have refurbished the building, and the front facade of the bar is similar to pictures of how Chez Josephine looked in 1926. The menu of the bar also has information about Josephine Baker’s life.

It was the legacy of Baker’s life that Bagley wanted to preserve.

In France, a building can be protected and conserved in its original state by the Ministry of Culture because of its historical or architectural relevance.

“When there is a place in danger of losing its patrimonial history, the Ministry of Culture can decide to give that place the right to be protected. This place is historic because of the architecture, as well as the demand of an association that they would like to conserve.In that case, there is a procedure to name, to secure and even the owner does not have the right to continue the work. Once the Ministry of Culture says the place is to be classed, they cannot touch it,” said Jean Gabriel De Mons, the Head of the Department of History, Memory and Associative Museums at the Paris City Council.

Bagley reached out to De Mon to intervene, but he failed to contact the Ministry of Culture in time. In an interview, De Mons said he couldn’t stop the sale from happening. Bagley did not notify the Ministry of Culture of the sale, because he was not aware of the rules.

Bagley’s activism for the cabaret did yield one positive result: On June 3, 2019, the City of Paris unveiled a plaque meters away from Baker’s old cabaret to honor her legacy in the city. The plaque recognized Baker’s stewardship of the cabaret from 1926 to 1928 to promote ‘Jazz and African American culture’, as well as her work as an artist, resistance fighter and civil rights activist.

“I feel sad that there is not much more we can do, but we are doing what we can do because there is a plaque. And true, there are plaques everywhere, but what else can we do with the way the system works? One thing that my mother would like is to show that she was American, but definitely also French and that the idea of the human race being the only race,” Bouillon-Baker said.

For Bagley, a plaque isn’t a consolation.

“For me, this isn’t ideally what I wanted. We are happy to have the plaque, but the cabaret should have been saved.”

Mark Beckford is as an assistant professor of journalism at Howard University. His recent research and journalism have explored media mergers in the Caribbean, Adverse Childhood Experiences in Baltimore and criminal justice in Ghana.

Have you subscribed to theGrio’s “Dear Culture” podcast? Download our newest episodes now!

TheGrio is now on Apple TV, Amazon Fire and Roku. Download theGrio.com today!