Apartheid president de Klerk portrayed as South African hero is classic whitewashing

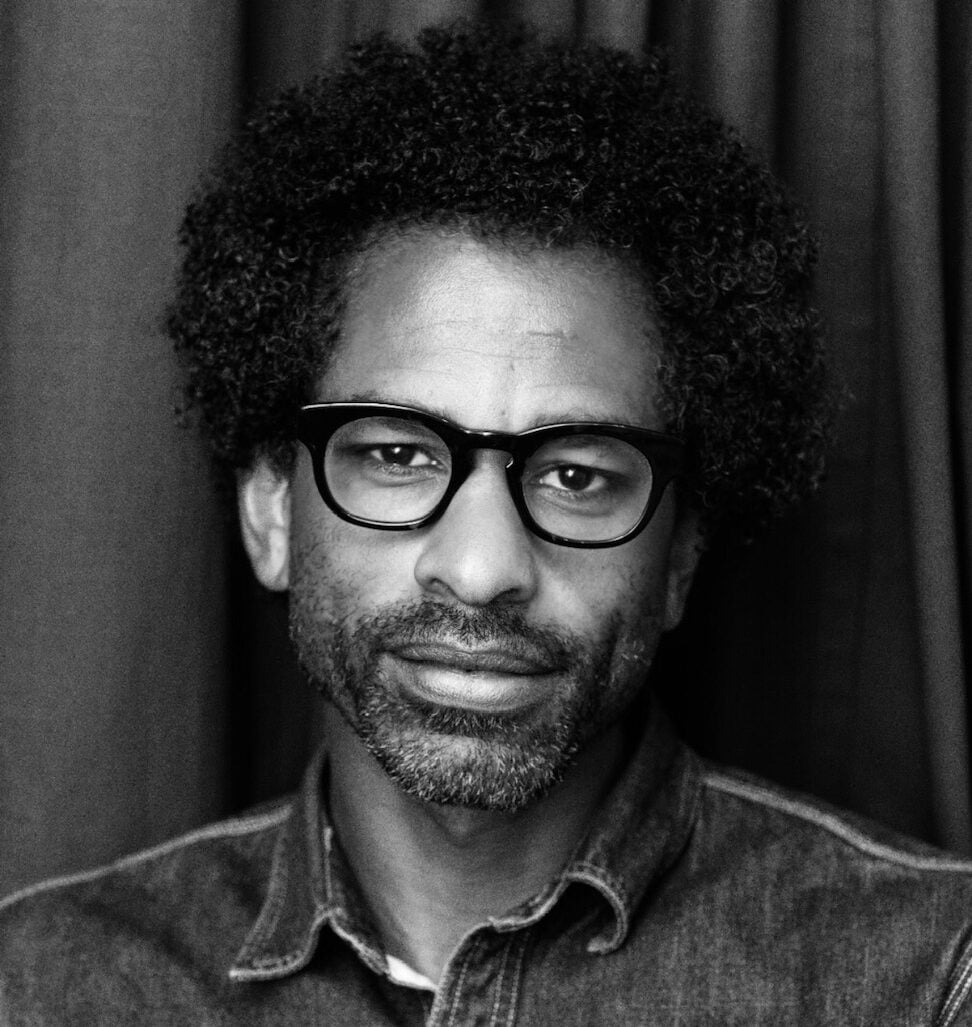

OPINION: theGrio's Touré writes that F.W. de Klerk was no hero who was one of the leaders of the most racist governments in modern history.

Oppressors will always try to rewrite history to make themselves seem better. They’ll justify slaughter by calling the victims “savages” or “uncivilized” or “rioters,” meaning that killing them is OK because they were lesser humans, if they were even human at all. This is used to explain the eradication of Native Americans from this country and the enslavement and long-term oppression of Black Americans.

The right wing’s attempts to erase critical race theory is just another example of oppressors trying to whitewash or clean up a past that now looks disturbing and needs justifying. It often falls to Black journalists, historians, and storytellers to tell the whole truth and so we rise to that job today because the former president of South Africa, F.W. de Klerk, has died and some people would like to recall him as a hero.

They say he was the one to release Nelson Mandela from prison after 27 years and the one who moved the South African government to dismantle apartheid. But these are not honest ways of explaining what happened. De Klerk was no hero. He is a villain, one of the leaders of the most racist governments in modern history, and a longtime supporter of apartheid who was boxed into a corner and did what he had to. Nelson Mandela said of de Klerk: “he was by no means the great emancipator.”

Some may point to de Klerk’s recent apology for apartheid, delivered when he could see death coming around the corner, but in 2020 when an interviewer asked him if apartheid was a crime against humanity he said no. Years after its end, he remained an apologist. To be clear, the United Nations General Assembly did condemn apartheid as a crime against humanity.

(When that vote happened guess who voted against approving that description? The United States. But I digress.)

The prime driver of what most governments will do most of the time is economics. Most governments want the local and national economy working smoothly because widespread prosperity ensures tax dollars from the masses and donations from the wealthy and votes from the people — if the economy is going well and most people have jobs and the ability to take care of their families and buy things, then they will be happy and they’ll vote to keep the powerful in power and major corporations will be satisfied and they’ll make donations aimed at keeping the powerful in power.

Every election usually comes down to how people feel about the economy. The end of apartheid came not because de Klerk and his peers in government suddenly realized that it was immoral. It came because both the system of apartheid and the global anti-apartheid movement were destroying South Africa’s national economy. The president before de Klerk, P.W. Botha, realized that change was inevitable and met with Mandela in prison to begin discussing change.

In the 1960s South Africa was experiencing economic growth second only to Japan — trade with the West was bringing in lots of money. But the harsh segregation imposed by apartheid meant that the Black majority was largely impoverished and lacked significant purchasing power. It’s impossible to have a functioning economy when 70% of the people can’t buy much and in the 1970s that fact began shrinking the nation’s economy.

Also, by the 1980s there was a global awareness that apartheid was a cruel, racist, immoral system. The U.S. and 24 other nations imposed harsh trade sanctions and there was a widespread divestment movement — no one wanted to invest in businesses that did business with South Africa. The country became a global pariah — its athletes could not attend the Olympics, major concert tours could not go there, the Pope refused to visit, and it became unacceptable for major countries and corporations to trade with South Africa. This brought the country’s economy to a halt and by 1987 it was growing at one of the slowest rates in the world, a stark turnaround from just two decades prior.

Also, in the 80s the global popularity of Nelson Mandela, who was then the world’s most beloved political prisoner, became a giant political problem for the apartheid government. They moved him from a harsh maximum-security prison to a facility that appeared more comfortable — to a nicer prison —and allowed him to meet with visitors from around the world in hopes that this would make it seem like his living conditions weren’t so cruel.

But Mandela’s interpersonal and political brilliance as well as his charisma and his insistence on loving his enemy and rejecting bitterness made him even more of a moral giant. The apartheid government released him in 1990 because it was in their best interest— perhaps that would lessen his status as a martyr. But he only grew.

Three years after Mandela’s release, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to him and de Klerk, which is a shameful stain on the Prize’s legacy. To equate Mandela and de Klerk, to put them on the same moral plane, to act like the two of them worked together to end apartheid is absurd. De Klerk was forced to release Mandela and end apartheid because of Mandela’s power and the world’s refusal to accept South Africa as long as apartheid remained.

De Klerk was Mandela’s jailer as well as the virtual imprisoner of millions of South Africans, and the world put an economic gun to his head and said release Mandela and end this system or die. De Klerk made the only choice he could. He does not deserve an award for finally doing the right thing when he was forced to. He does not now deserve to be discussed as a hero or even a force for good. If there is justice in the afterworld, there should be a place waiting for him in hell.

Touré is the host of the podcasts Toure Show and Democracyish and the podcast docuseries Who Was Prince? He is also the author of six books.

Have you subscribed to the Grio podcasts, ‘Dear Culture’ or Acting Up? Download our newest episodes now!

TheGrio is now on Apple TV, Amazon Fire, and Roku. Download theGrio today!