The United States’ history of redlining and racist transportation design practices may finally be addressed in a very real way as elected leaders have an opportunity to use federal dollars, secured by President Joe Biden and Democrats in Congress, to begin infrastructure projects intended to reconnect Black neighborhoods with the worlds they’ve long been shut out from.

In Richmond, Virginia, a very real conversation is being had about capping Interstate 95 in the area or constructing a bridge over at least a portion of the 179-mile stretch of Virginia’s I-95 superhighway. The objective is to reconnect Jackson Ward, a once culturally and economically rich and predominantly Black district that was split by the construction of I-95.

This conversation has a scope that would not just impact that area but a traffic pattern that spans 15 states — the longest north-south interstate, running 1,920 miles, from Florida to the Canadian border with 670 exits.

However, with all the acclaim over this highly traveled roadway, it impedes the reconnection of the predominantly Black community of Richmond’s Jackson Ward, an area established 150 years ago and was split in half in the 1950s with the construction of the motorway.

Several local Richmond-area community groups have been working for years to reconnect Jackson Ward, which was once considered the “Harlem of the South.”

Democratic U.S. Congressman Donald McEachin, who represents Richmond, says the history of the community is rich, telling theGrio, “Jackson Ward historically came together when former slaves and African-American veterans came back to Richmond and basically settled in one particular area. The area really became a vibrant hub. It was Wall Street. This is before Tulsa. It was our entertainment capital.”

Last year, the Richmond city council adopted its “Richmond 300” master plan to create a more “equitable, sustainable, and beautiful future for all Richmonders” by the city’s 300th birthday in 2037. Part of the master plan includes ideas on capping I-95 near Jackson Ward.

The plan is not yet funded, however, the city is hoping to receive federal funds for the project. Staffers in the office of Congressman McEachin acknowledged there’s $1 billion in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to establish a grant program for reconnecting communities, and it stands to gain another $3.95 billion through the House-passed version of the Build Back Better Act that is awaiting Senate action. However, that funding amount could change in Senate negotiations.

In the 1950s, the Jackson Ward community was split with the construction of the infrastructure project that cut an entire city block-sized hole into that neighborhood, allowing for the now massive roadway to roll through the heart of the community, separating a number of streets, never allowing it to regain its once heralded glory.

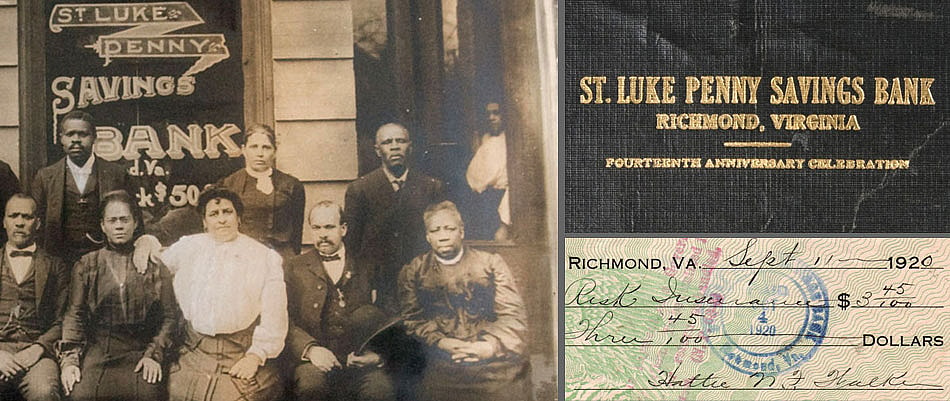

Jackson Ward was once a vibrant Black socioeconomic community that at one point resembled that of Tulsa, Oklahoma’s Black Wall Street. The town was the home of a Penny Savings Bank, a department store, the Hippodrome Theater, a hotel, an insurance company, a newspaper and more.

The St. Luke Penny Savings Bank was owned by Maggie Walker, deemed America’s first Black woman to ever do so. The National Park Service has designated a property owned by Walker as a national historic site.

Congressman McEachin cosponsored the Reconnecting Communities Act back in April in efforts to help unify the split in Jackson Ward. McEachin was school aged when President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 into law. The infrastructure project known as the Interstate Highway System forever scarred the economics of the Black financially-viable area, among others.

“Folks decided to come right through the heart of Jackson Ward, and they did it in such a malicious fashion … the residents of Jackson Ward couldn’t get on to I-95 from Jackson Ward,” McEachin told theGrio.

“It was definitely something that was not meant for them to use. People could come off of the highway and go through Jackson Ward if they wanted to, but the residents couldn’t get on, at least not at that juncture.”

The effort to join Jackson Ward again to the rest of the Richmond area has been in the works for several years. However, it is not yet funded. In recent weeks, U.S. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg took a walking tour of the community and listened to efforts to correct the racism that broke that community in half.

“Transportation should always be about connecting, never about dividing,” said Buttigieg.

The transportation secretary also recently traveled to Syracuse, New York over Interstate 81 that, just like in Richmond, divided a predominantly Black community. Buttigieg’s walking tour was an effort to promote the Biden administration’s reconnecting communities program.

U.S. Congresswoman Barbara Lee of California told theGrio that Jackson Ward is not an anomaly. “I remember in El Paso, Texas, which is where I was born and raised, an interstate came right through our communities. In California right now in the district that I represent, there’s a freeway that cuts off West Oakland from downtown,” said Congresswoman Lee.

“I think every member of the [Congressional] Black Caucus and everyone who has African-American constituents can cite areas that have been just dismantled and [it] has been really traumatic for the Black community and has really diminished our African-American populations in these communities.”

In downtown Baltimore, Maryland there is a highway to nowhere that was left after not being connected to other freeways as originally planned. This road split a low-income and predominantly Black area in Baltimore City. The issue of racism being built in the roads is part of a long list that includes cities like New York and Los Angeles.

In Chicago, sources contend that the Dan Ryan Expressway is a heavy lift to deconstruct but there are other efforts to change the infrastructural racism built into the South Side of Chicago.

Abigail Cooper, a history professor of Brandeis University, is currently teaching her curriculum on the 1619 Project. Cooper told theGrio that the conversation on race and infrastructure “gets sidetracked whenever we talk about infrastructure as though roads and bridges are race neutral.”

“State and federal government[s] have time and time again … disinvested in Black communities,” she added. “When we look at this infrastructure bill we are looking at highways in order to separate White communities from Black communities. We are looking at bridges, property evaluations that absolutely followed the FHA redlining.”

Cooper described the Biden-Harris administration’s efforts as an attempt to “connect past to present.”

That connection is expected to come from the Biden Transportation Department through a $1 billion competitive grant from the Reconnecting Communities Program in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. DOT will be making communities aware of the opportunity of funding, all before reviewing projects that could ultimately receive federal support.

The billion-dollar fund in the infrastructure law isn’t the only source of funds available to reconnect communities and provide economic opportunities. For example, recently DOT awarded RAISE grants to cities such as El Paso, Texas and Atlanta for projects to cap highways.

Secretary Buttigieg was also in Baltimore recently to announce a RAISE grant that will help fund the east-west priority corridor, connecting people to jobs and economic opportunity with rapid bus transit, and this summer DOT selected South LA to receive an INFRA grant using new criteria to consider impact to disadvantaged communities.

With a seriousness of outward expression on her face, Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot is firm on what needs to happen for the Windy City. Lightfoot was in the nation’s capital with nonstop lobbying, pounding the pavement and taking part in meetings at conference room tables at the White House and beyond for the Windy City.

Earleir in December, Mayor Lightfoot was in Washington holding a slew of meetings with White House officials and former New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu, who has been tapped by the Biden administration to implement funds from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Framework to rebuild America’s roads and bridges.

Mayor Lightfoot is using every lever she has to make sure that her city gets needed federal funding, particularly for distressed areas that have food deserts and lack of access to opportunity.

One project that Lightfoot is focused on is the expansion of the city’s red line transit system into the disadvantaged areas of the South Side of Chicago where the Dan Ryan Expressway cuts through the heart of the Black community where, in some cases, it does not allow for easy access for many of its residents.

Following the transition from the Trump administration to the Biden administration, Obama administration Transportation Secretary Anthony Foxx told the incoming Biden White House that the issue of deconstructing the racism built into America’s infrastructure was an issue that needed to be tackled.

Now the Biden administration is leaving it to communities to determine if they can use funding from the federal government to essentially break up the racism built into roadways and communities that were constructed before the Civil Rights Act as a way to keep Black and minorities apart from White communities.

Congresswoman Lee said this moment is about repairing the “decades and decades of damage.”

“People wonder sometimes what systemic racism is? This is it.”

Have you subscribed to theGrio podcasts “Dear Culture” or “Acting Up?” Download our newest episodes now!

TheGrio is now on Apple TV, Amazon Fire and Roku. Download theGrio.com today!