This is going to be a purely subjective list of my all-time favorite Sidney Poitier movies, which means it’s going to make many readers very cross with what they see as omissions, unforgivable, egregious, or otherwise. The best I can do to address their grievances is to try citing some of the other movies within each of my entries as contrasts, comparisons and amendments, whenever relevant.

And so, we begin (in chronological order and with a few spoilers surfacing):

Red Ball Express (1952): This dark, edgy World War II film inspired by the predominantly Black trucking unit that carried out dangerous missions to supply General George S. Patton’s troops was Poitier’s third film after 1950’s No Way Out and 1951’s Cry, the Beloved Country. Though billed below white actors Jeff Chandler and Alex Nichol, Poitier gave a performance exciting enough for critics at the time to single out in reviews. It still stands out in Poitier’s career as one of the few times he is depicted as an uncompromisingly Angry Black Man, resentful and emotionally scarred by the racism he’s encountered in his life, even if the sources of those wounds are never specified.

Edge of the City (1957): Poitier’s emergence as a bona-fide movie star began with his portrayal of Tommy Tyler, a stevedore working the west side Manhattan docks who befriends Axel Nordmann (John Cassavetes), an emotionally stunted white drifter. As he often would in years to come, Poitier played Charlie as a paragon of decency, mentoring Axel to stand up for himself. It won’t spoil too much to disclose that things end badly—and to some contemporary audiences, mawkishly—for this beautiful friendship. Yet the movie endures, as much for its gritty urban atmosphere as for Poitier’s exuberance.

The Defiant Ones (1958): Two convicts, an embittered Black man (Poitier) and a white, racist punk (Tony Curtis) flee from a Deep South chain gang shackled together in hatred, but finding their common humanity once they’re unchained. This neon-lit, jury-rigged metaphor of the struggle for True Brotherhood in America earned multiple Oscar nominations, including one for Poitier as best actor. The movie’s controversial ending, where Poitier’s character sacrifices his freedom to join Curtis back in stir, was derided by Black audiences who rooted for Poitier to keep heading north. Whatever their reservations with the outcome, those audiences joined Hollywood and the rest of the moviegoing public in hailing Poitier’s onscreen power.

A Raisin in the Sun (1961): Defiant Ones aside, it’s possible Poitier was never more explosive and mercurial onscreen as he was in the role he helped create on the Broadway stage in Lorraine Hansberry’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play. His Walter Lee Younger is a swaggering welter of raw nerves, inchoate fury, and wounded, if lingering, self-respect. There is emotional complexity in Walter Lee that Poitier would rarely find in roles that would otherwise enhance his fast-rising stardom.

The Slender Thread (1965): After he won the best actor Oscar in 1963 for playing handyman-angel to German nuns in Lilies of the World, Poitier used his newfound power to press for leading roles in movies that weren’t overtly or necessarily grounded in racial themes. The most modest and, likely, best of these efforts starred Poitier as Alan. a med student working the evening shift at a suicide-prevention center where he receives a phone call from Inga (Anne Bancroft), an unhappily married woman who says she’s taken a lethal dose of pills and wants to talk to somebody while waiting to die. From then on, Poitier’s Alan is trying to keep Bancroft’s Inga awake and talking long enough for rescue workers to locate her. It seems even today more like a routine made-for-TV movie, but Poitier and Bancroft, though never in the same room, throw off intense sparks together.

Duel at Diablo (1966): I’m only guessing, but Poitier’s portrayal of a dandified, cigarillo-smoking cowboy here likely happened in part because the actor had decided that Black children had gone long enough without a Black western movie hero to identify with. In this western (which boasts one of the most heart-filling tracking shots ever to open a film), Poitier’s ex-Buffalo Soldier is more a wily sidekick to James Garner’s vengeful frontier scout. Didn’t matter either way to me. Like many westerns I’d watched at that point in my life, I was ready for Sidney Poitier to be a dandified cowboy and he didn’t disappoint me.

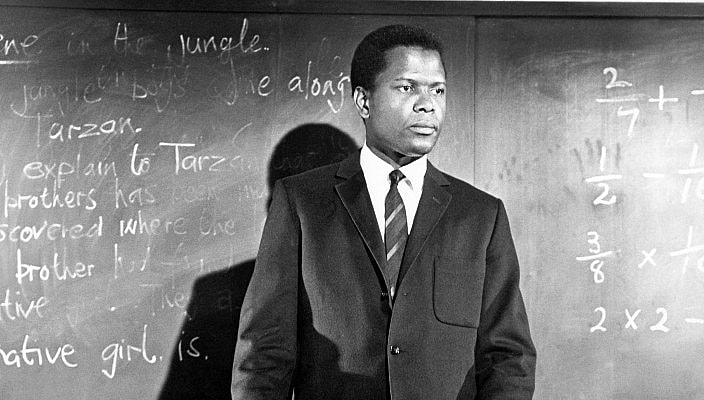

To Sir, with Love (1967): The year that Sidney Poitier blew up really, really big began with the release of this British-made adaptation of E.R. Braithwaite’s memoir of teaching disruptive, mostly white working-class teenagers in a London secondary school. Back in 1955, Poitier was the callow at-risk student with a chip on his shoulder in Blackboard Jungle. Just 10-plus years later, he was the designated grownup who figures out how best to keep his rowdy insolent students attentive. “Sir” wasn’t Lear, Hamlet or, even, Walter Lee. He was simply Sidney Freaking Poitier pulling off a routine star turn and it helped pull in more than $42 million in U.S. box office receipts, making it the sixth highest-grossing movie in America that year.

In the Heat of the Night (1967): My all-time favorite, not least because Poitier’s performance as Philadelphia’s top homicide cop Virgil Tibbs may well have been his purest display of screen acting; refined and rigorously contained. As Bill Gillespie—the bellicose police chief of tiny Sparta, Miss., who all but dragoons Tibbs into helping him and his undermanned department solve a murder—Rod Steiger deftly played off Poitier’s slow-boiling restraint with colorful, mouthy swagger and, along with the film, was rewarded with an Oscar. Viewers today don’t talk as much they should about Tibbs’ commanding composure. But everybody remembers the moment when it goes away: when shady, arrogant Mister Endicott (Larry Gates), the very embodiment of Mississippi’s landed white gentry, responds to the “uppity negro’s” relentless interrogation by slapping his face. Tibbs, instead of turning the other cheek, slaps back, making time stop both in the movie and, one heard, in movie houses from sea to shining sea. “What are you going to do about it?” Endicott asks Gillespie. “I don’t know.” the chief mutters back and it’s that unresolved stand-off that lingers in memory. In many ways, we’re all still trying to answer that question.

For Love of Ivy (1968): After Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, the 1967 romantic comedy about an impending interracial marriage in which Poitier was—finally!—allowed to kiss a white woman (played by co-star Katharine Hepburn’s niece Katharine Houghton), the freshly minted box-office powerhouse expressed his desire to make a romantic comedy with a Black female lead. So, he came up with the idea for a story about a Black housemaid, the eponymous Ivy Moore (Abbey Lincoln), who decides to leave the rich Long Island family for whom she’s been working for nine years for a new life learning secretarial skills in New York City. To keep Ivy from leaving, the family heir (Beau Bridges) fixes her up with Jack Parks (Poitier), a fast-talking truck company executive, so she’ll feel fulfilled enough with a steady fellow in her life to forego the city life. In form, if not always in execution, For Love of Ivy feels like a relic of the gaudy 1950s comedies of swank romantic deception. But Black audiences, especially adults, loved watching a slick, fluffy, unapologetically contrived “rom-com” they could call their own. Poitier is a persuasive romantic lead, but in retrospect, Virgil Tibbs is somehow wittier. The movie really belongs to Lincoln, a great jazz vocalist and regally beautiful woman, who was rarely given the chance to show what she could do as a screen actress.

Uptown Saturday Night (1974) & Let’s Do It Again (1975): After he’d all but reached apotheosis as a screen star, Poitier finally scratched the itch he had for directing movies as well as, maybe more than, acting in them. And these two unruly, but warm-hearted comedies represent his best work behind the camera. Written by Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Richard Wesley, both movies star Poitier and Bill Cosby as, respectively, Steve and Wardell in Uptown Saturday Night and Clyde and Billy in Let’s Do It Again. Though the names are different, they’re basically the same guys in both movies: hard-working blue-collar types who have to dig themselves out of a financial pickle past cordons of gangsters, grifters and assorted lowlifes. Comedy was never Poitier’s strong point as an actor. But as a director, he had enough taste and timing to give Cosby, his longtime friend Harry Belafonte, and his all-star casts of Black stage legends (Roscoe Lee Brown, Rosalind Cash, Calvin Lockhart) and standups (Richard Pryor, Flip Wilson, Jimmie Walker) plenty of room to be as funny as they wanted.

Gene Seymour has written about movies, music, literature, politics, and (even) baseball for such outlets as CNN.com, The Nation, The New Republic, BookForum, and the Los Angeles Times. He lives in Philadelphia.

Have you subscribed to theGrio podcasts “Dear Culture” or “Acting Up?” Download our newest episodes now!

TheGrio is now on Apple TV, Amazon Fire and Roku. Download theGrio.com today!