Rep. Joseph H. Rainey, born into slavery in 1832, was honored Thursday for being the first Black member of the House by formally having a room in the Capitol named after him. Top lawmakers and a descendant turned the ceremony into something more than that.

No. 3 House Democratic leader James Clyburn, Rainey’s great-granddaughter Lorna Rainey and others used the event to say the battle for racial justice and voting rights that Joseph Rainey championed must continue.

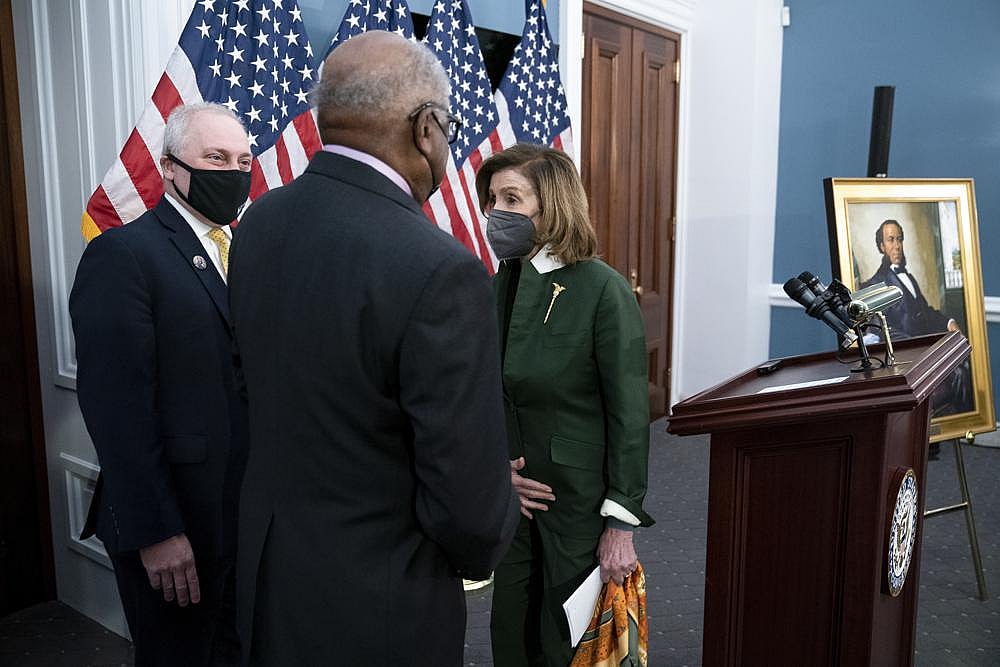

The brief event featured speeches delivered beside a portrait of Rainey, sitting with legs crossed in the Capitol and sporting prominent mutton-chop sideburns and a dark suit. It came during Black History Month and as Republican-run states have enacted voting restrictions that in some cases are expected to affect minority voters.

“I have children. I have grandchildren,” said Clyburn, who like Rainey did represents a district in South Carolina. “I want them to feel as proud of this country as I am.”

Clyburn noted that eight African Americans were elected to the House from his home state during the 19th Century but said, “The problem is there’s 95 years between No. 8 and No. 9,” who is Clyburn himself, first elected in 1992. “Anything that’s happened before can happen again.”

“If Joseph Rainey could accomplish so much during his time, then certainly you can be the ones to get the people’s work done,” his great-granddaughter told the small audience, which included lawmakers. “As we honor this man, please let us remember what he stood for, what he put his life in danger for and why his legacy endures today.”

The modest room now bearing Rainey’s name is on the first floor of the Capitol and was used by the House Committee on Indian Affairs, on which he served. A plaque in his honor was placed outside the room.

It’s currently used by aides to House Minority Whip Steve Scalise, R-La., who said of Rainey, “He didn’t just come up here to hold the title. He came up here to make a difference, and make a difference he did.”

Never formally educated, Rainey was forced to help build Confederate fortifications around Charleston, South Carolina, and to work aboard a blockage-running ship.

He escaped to the British island colony of Bermuda and returned to South Carolina in 1866, where he helped found the state’s Republican Party. He was elected to Congress and sworn into office in December 1870, replacing a lawmaker who had resigned.

Reelected four times and serving during Reconstruction, Rainey’s first major speech came in April 1871 in support of the Ku Klux Klan Act, which expanded federal law enforcement powers in the South. He served with 13 other African-American lawmakers during Reconstruction, all of them Republicans.

The Constitution, Rainey said, was written to protect “the humblest citizen, without regard to rank, creed, or color.” President Ulysses Grant signed the legislation into law days later.

Rainey received death threats from the Klan in 1871, including a letter written in red ink to him and other Black officials that he provided to a newspaper that said, “Your doom is sealed in blood.” He was an advocate for rights for working people, immigrants, former slaves and supported self-government for Native American tribes.

In 1874, Rainey became the first Black to preside over the House when he oversaw a debate on a spending bill for Native American reservations. The Springfield Republican, a Massachusetts newspaper, contrasted Rainey’s appearance with “the days when men of Mr. Rainey’s race were sold under the hammer within bowshot of the Capitol.”

Rainey died of natural causes in 1887, a few months after contracting malaria. He was 55.

According to the Senate website, Hiram Revels became the first Black senator when he was sworn into office in February 1870, months before Rainey’s arrival.

GOP Rep. Tom Rice, whose South Carolina district includes the town of Georgetown where Rainey was from, said his grandparents lived just blocks from Rainey’s house. “Can you imagine the pressure that he felt and the obstacles that he had to overcome,” Rice said.

In a moment of bipartisan comradery rare these days, Rice said he’d proposed a bill naming a local post office after Rainey that wouldn’t have succeeded without Clyburn’s support.

Standing behind Rice, Clyburn deadpanned, “That’s correct.”

TheGrio is now on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku, and Android TV. Also, please download theGrio mobile apps today!