When I saw a cotton gin at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) in Washington D.C., there was a sign below that read, “Pick a bail of cotton.” Right at that moment, I began singing:

“Oh, Lordy! (pick a bale of cotton)

Oh, Lordy! (pick a bale a day)

Gonna jump down, pick a bale of cotton,

Gonna jump down, turn around,

Pick a bale a day”

I was taught that song in middle school in 7th grade. I even remember my music teacher telling us how to pronounce the words: “Say ‘pick a bale’a cotton’ not pick a bale of cotton.’” You may have guessed by now, but it was a white teacher, and I went to a school that was 99% white students.

Thinking about it now, I say to myself, “The nerve of a white person telling me and others this is what Black people spoke like.” But had she explained that Black people sang and spoke like that because they were slaves and white slave masters didn’t allow them to read, that would’ve been different.

Without perspective and context, history is mere facts; trivial footnotes are only good for passing a school test or impressing folks at a social gathering. Having perspective and context with history, however, is a pathway to wisdom — the foundation for evolving oneself and progressing the evolution of those around you.

When walking through the halls of the NMAAHC, you’ll realize that it’s not only about the events of the past. It’s about the rationale that led to those events and the parallels with the current events.

In an American system that thrives on white supremacy, the number one tactic of hindering Black American progress is removing knowledge of self. People trying to discredit critical race theory in the media as of late is only the latest example. The NMAAHC is proof positive that America depends on the systemically relegating Black people to servitude, whether literally or subliminally.

The great thing about the NMAAHC is that it fills the gaps left by America’s institutions. Most Black American students are taught little, if anything, about the history of the African Diaspora beyond the obligatory mentions of the Atlantic Slave Trade, the Civil Rights Movement, and a few things in between. Once you enter the crux of the museum – The Journey Toward Freedom: 15th to 21st centuries – you will see that there is way more to the story.

From that first level, “Slavery & Freedom 1400 – 1877,” you get a definitive introduction to Africa’s place in the world. You see how it was thriving and evolving, advancing in culture, art, music, and science. Sound familiar? You also see how Europe was evolving concurrently and how the decision to enslave Africans as part of an emerging global economy was made.

The sight of artifacts of the remains of a Portuguese slave ship, the São José, is more the enough to incite menacing feelings of rage, sorrow, and discontent. However, we all knew that slave ships existed before. We even knew about the Nat Turner Slave Rebellion, which is extensively mentioned in the museum as well.

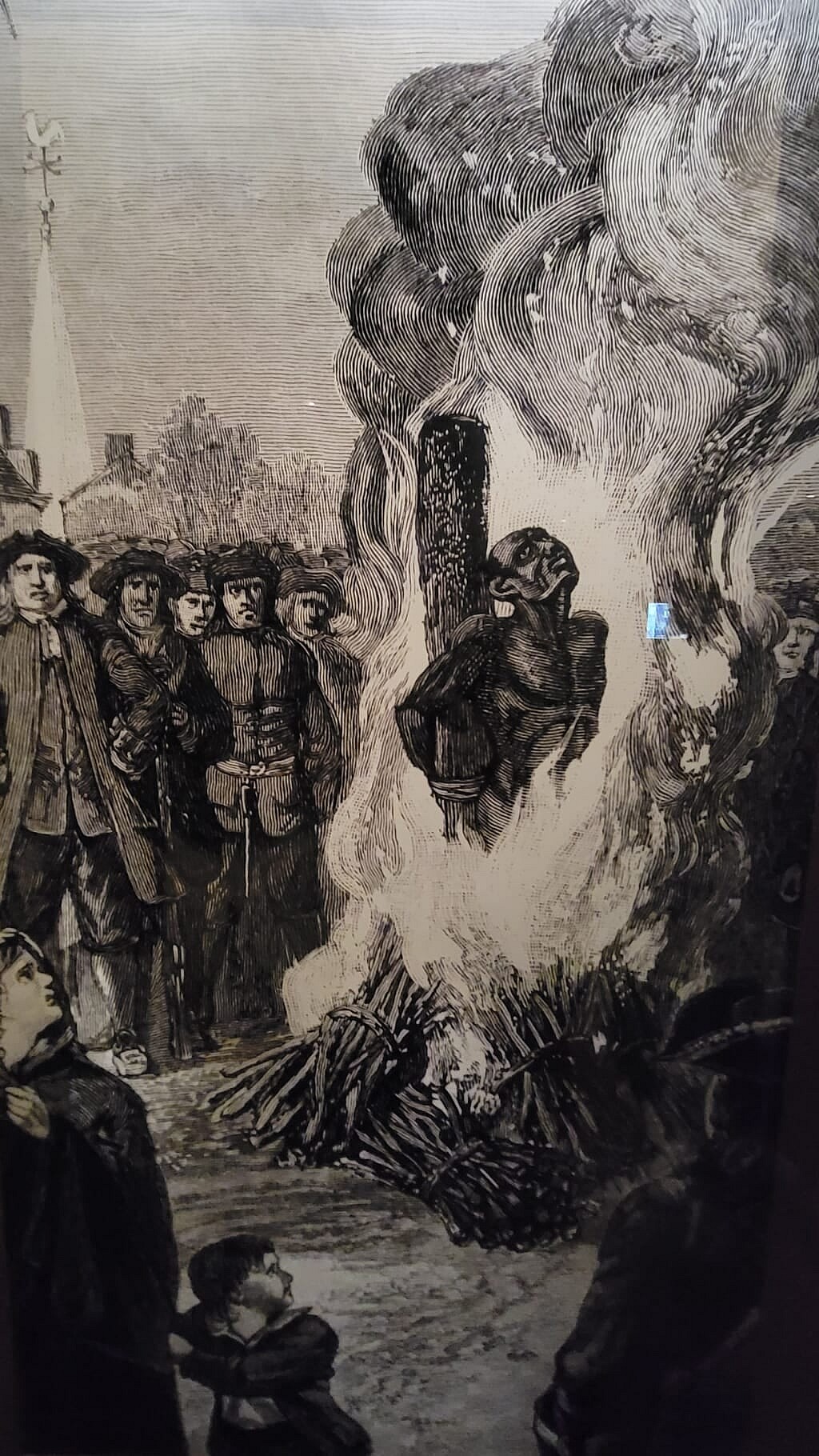

What I didn’t know, and what many of you still may not know is there was a rebellion called The New York Conspiracy. I learned in the NMAAHC that in 1741 a group of enslaved Blacks joined forces with poor whites to rebel against rich whites in New York, to make a new king and governor.

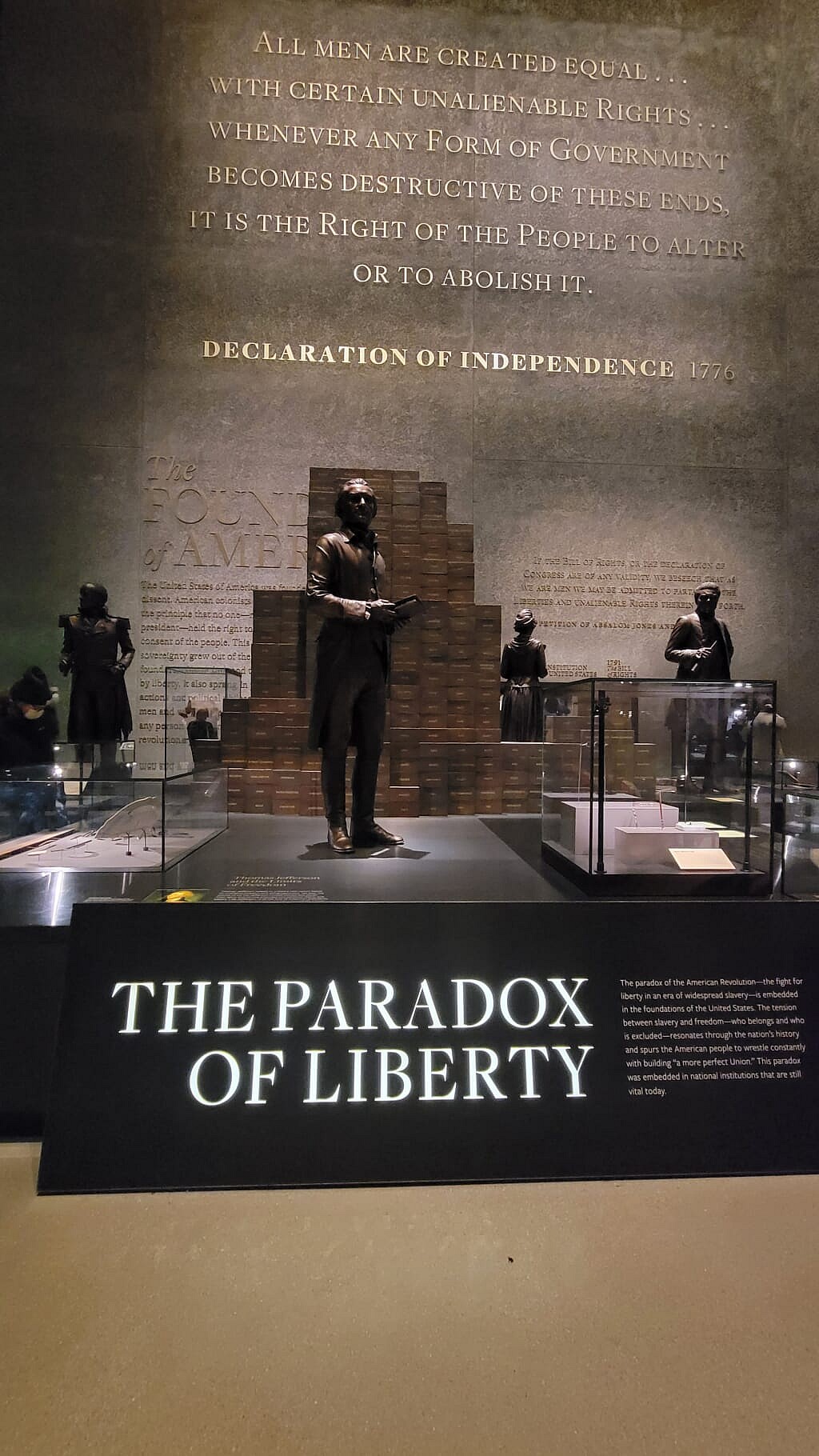

Nuggets of important history found in this museum, while all but omitted elsewhere, further illustrate, what the museum calls, “The Paradox of Liberty.” Men like Thomas Jefferson claimed all men are created equal for their own personal advancement. But in the shadows of his own prejudice, Black women like Elizabeth Freeman and Phillis Wheatley were actually doing the work to make sure that the Black community at large was protected by that same sentiment.

It’s these types of revelations that make the NMAAHC so crucial for Black people of all ages. Seeing street signs of 19th-century haven freed Black communities like Nicodemus, Kansas, Freetown, Texas, and Smithfield, Alabama, indicates the communal, tribal heritage of Black Americans that permeates from their African DNA.

This museum’s best asset is that you have to come more than once to get the whole experience. Not only because schools won’t do it and because it’s visually stunning, but it makes you want to look things up further on your own. The more you look up independently, the more you’ll be inspired to return to the NMAAHC for more.

Open from 10:00 a.m. to 5:30 p.m., you could only take in about 10 percent of all the NMAAHC has to offer even you were there all day. I found myself personally getting wrapped up in the gift shop for an hour, let alone the Reconstruction exhibition (never knew that Howard University was co-founded by a white man). You’ll want to come back again. I know I do.

Connecting the dots between African music origins via spirituality and vocal improvisation to the Afrofuturism literature of Octavia Butler to the sight of George Clinton’s original mothership from Parliament’s 1970’s touring days let me know that everything we do has a through line. It’s not just about the enduring spirit of Black Americans in the face of prejudice, it’s about understanding the richness and fullness of our genetic makeup to innovate and adapt in any situation.

The NMAAHC is a marvel in several senses. Architecturally, its design derives from Nigerian sculptor Olowe of Ise and ornate ironwork made by freed and enslaved craftspeople. It’s also a revelation of achievement and possibilities. It should be a required visit for any descendent of the African Diaspora; no different from a Muslim man or woman making a pilgrimage to Mecca.

TheGrio is now on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku, and Android TV. Also, please download theGrio mobile apps today!