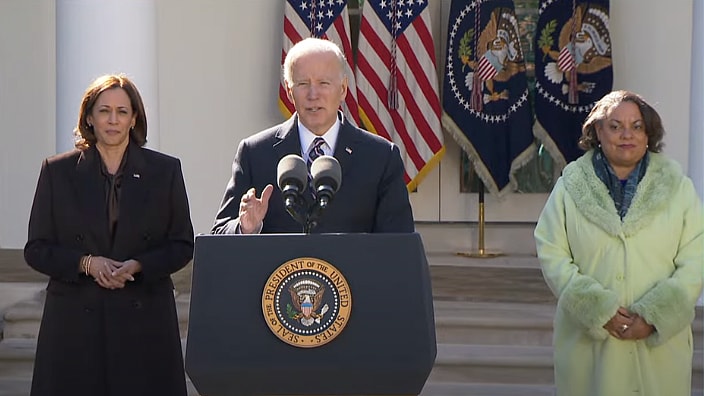

It was a big day in Washington with a lot of emotion after President Joe Biden on Tuesday signed into law the nation’s first anti-lynching legislation after decades of failed attempts to establish federal accountability for racial violence.

President Biden signed into law H.R. 55, also known as the Emmett Till Antilynching Act, which makes lynching a federal hate crime.

“Lynching was pure terror to enforce the lie that not everyone belongs in America, not everyone is created equal,” said Biden in his remarks after signing the historic bill into law. “Terror to systematically undermine hard-fought civil rights…not just in the dark night but in broad daylight, innocent men, women and children, hung by nooses from trees, bodies burned and drowned and castrated.”

Biden added, “Their crimes? Trying to vote, trying to go to school to try and own a business or preach the gospel. False accusations of murder, arson or robbery, simply being Black. Often the crowds of white families gathered to celebrate the spectacle, taking pictures of the bodies and mailing in the bus postcards.”

President Biden also acknowledged that the law “is not just about the past,” declaring “It’s about the present and our future as well. From the bullets in the back of Ahmaud Arbery to countless other acts of violence, countless victims known and unknown.”

U.S. Congressman Bobby Rush of Illinois, who was instrumental in drafting the bill that he also introduced last year in the House of Representatives, said “Today, we correct this historic and abhorrent injustice.”

A spokesperson for Congressman Rush emphasized that the new law ensures that the “definition of lynching is more than someone getting hung from a tree.” The law defines lynching as a conspiracy to commit a hate crime that results in death or serious bodily injury.

The Antilynching Act was passed in the House of Representatives on Feb. 28, 2022, by a vote of 422-3. The three Republicans who voted against the historic bill were U.S. Representatives Andrew Clyde (R-Ga.), Thomas Massie (R-Ky.), and Chip Roy (R-Texas). The U.S. Senate, however, voted unanimously to pass the bill that makes lynching a crime with the maximum penalty of 30 years behind bars. A previous version of the legislation set the maximum sentence at 10 years.

Sponsors of the bill, including Rep. Rush, contend more than 200 attempts were made since 1900 to have federal antilynching laws in place.

In a statement to theGrio earlier this month, Rush said, “The Emmett Till Antilynching Act will ensure that anyone who commits the monstrous act of lynching will be prosecuted under federal hate crime laws — as they should have been all along — and will send a clear message that our nation is finally willing to reckon with the gruesome history of lynching in America.”

Lynching dates back to the eras of U.S. slavery and Jim Crow when people, overwhelmingly Black, would be hung to death from trees. More than 6,500 Americans were lynched between 1865 and 1950, according to a recent report from the Equal Justice Initiative.

Attending Tuesday’s signing ceremony at the White House were family members of the law’s namesake, Emmett Till, a 14-year-old Black boy from Chicago who was lynched in Money, Mississippi while visiting family. The teen was kidnapped from his home by a mob of white men who beat, shot and drowned him for allegedly flirting with a white woman. The woman at the center of the accusation of Till, Carolyn Bryant Donham, would admit she lied decades later.

Also in attendance at the signing ceremony were the descendants of activist and reporter, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, who took up the cause of antilynching efforts throughout her life in the early 1900s. According to the White House Historical Association, Wells-Barnett received national acclaim for her fight against the frequency of lynchings in the South. She lobbied seven U.S. presidents from William McKinley to Herbert Hoover who gave little to no support.

During her remarks at Tuesday’s signing ceremony, Vice President Harris praised the courageous work of Ida B. Wells-Barnett and the important role of the Black press.

“[Wells-Barnett] used her skill, her profession, her calling as a journalist…to help open the eyes of our nation to the terror of lynching, which speaks of course to the role that we have known also historically – I’m going off-script for a moment – about the importance of the Black press,” said Vice President Haris, “And the importance of making sure that we have the storytellers always in our community who we will support, to tell the truth when no one else is willing to tell it.”

Wells-Barnett’s great-granddaughter Michelle Duster, who stood beside President Biden and Vice President Harris during the ceremony, also delivered remarks.

“Through her writing and speaking, she exposed uncomfortable truths that upset the status quo. The truth that lynching was being used as an excuse to terrorize the Black community in order to maintain a social and economic hierarchy based on race,” said Duster.

“And for that her life was threatened. Her printing press was destroyed. And she was exiled from the south. But despite losing everything, she continued to speak out across this country and Great Britain about the violence and terror of lynching.”

Leon Russell, chair of the National Board of the NAACP said theGrio of Wells-Barnett, “As a member of the National Negro Committee which changed its name to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in 1909, she and others saw the violence inflicted.

“The prime example of that violence was lynching. So early on, she and others called for anti-lynching legislation making the extrajudicial murder of Black people by hanging (principally) a federal crime.

He added, “She understood that changing minds and attitudes was futile. Changing public policy and therefore behavior was absolutely necessary.”

TheGrio is now on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku, and Android TV. Also, please download theGrio mobile apps today!”