America’s oldest medical society apologized Wednesday for honoring a dermatologist who experimented on mostly Black prisoners during a 23-year period, infecting them with LSD and an Agent Orange component called dioxin.

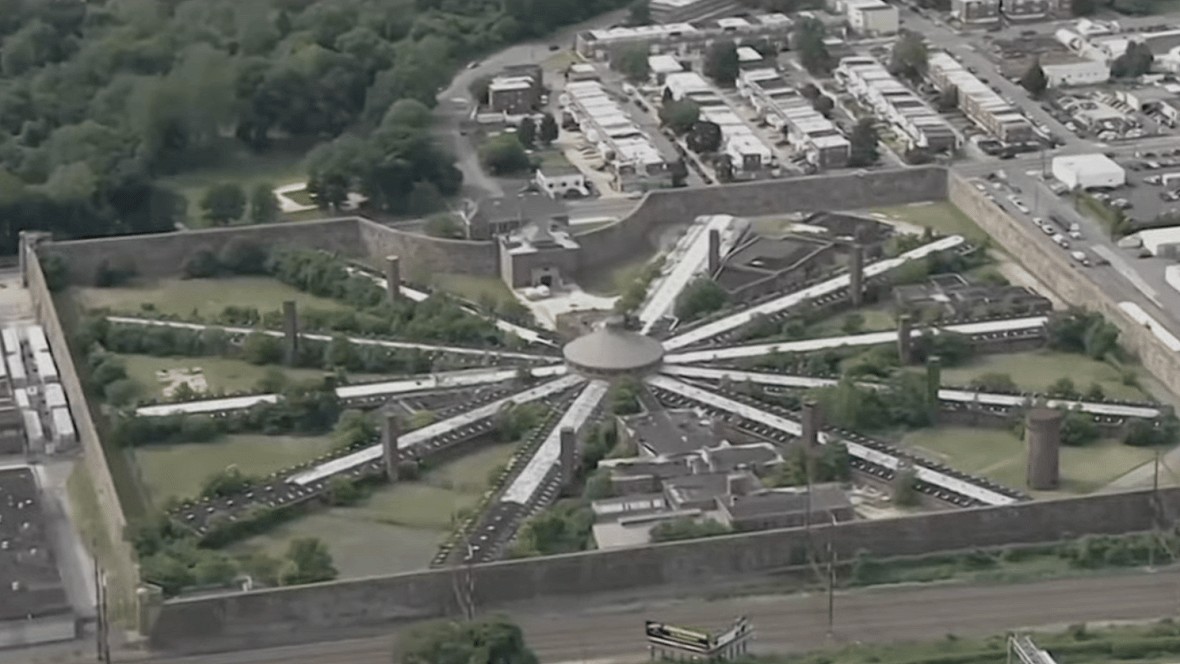

According to The Philadelphia Inquirer, the College of Physicians of Philadelphia apologized for its affiliation with Albert Kligman, who exposed prisoners at the city’s Holmesburg Prison to viruses and fungi when he performed tests on them between 1951 and 1974.

The organization said it also rescinded Kligman’s Distinguished Achievement Award.

“The College of Physicians offers its deepest sympathies for those who suffered, including their families, and it apologizes for its silence in not expressing these sentiments sooner,” the organization said in a statement, The Inquirer reported. “Though this apology is long overdue, it is no less heartfelt for the delay.”

Julia Haller, board president of the College of Physicians, said the organization decided to apologize publicly after meeting with Philadelphia Inmate Justice Coalition members.

Kligman had been a College of Physicians fellow since 1954. In 2003, he received the society’s Distinguished Achievement Award long after there were press stories of the tests, legal actions and a book describing the magnitude of his harm.

Haller stated that she and her colleagues have been analyzing records to understand more about the debate around the decision to honor Kligman. However, she has yet to determine what took place.

In the 1960s, Johnson & Johnson recruited Kligman to compare the effects of the baby powder ingredient talc with those of the carcinogenic asbestos. He injected about a dozen inmates at Holmesburg. He also worked with Dow Chemicals and the Pentagon.

Leodus Jones, who had endured Kligman’s experiments while a prisoner in Holmesburg in the 1960s, was one of several who protested the 2003 award presentation.

Jones recalled being injected with a rare disease from India for $10, which would increase to $15 if he developed an abscess. At the time, he believed that the paltry sum that Kligman paid would help him buy items in the commissary and ease the financial load on his family.

Before Jones’ death in 2018, he claimed in a media interview that the skin on his torso appeared “like a pinto pony,” but he didn’t care because he needed the money.

According to Allen Hornblum, who wrote the 1998 book, “Acres of Skin,” detailing the scope of the experiments, Kligman boasted about his access to prisons and “acres of skin” in pitches to potential doctors for his practice or to entice clients for pharmaceutical research.

Hornblum said the college’s apology is especially significant because it shows the medical community acknowledging its sins of omission, which included honoring Kligman during his lifetime while disregarding the vulnerable people he hurt.

Kligman, who died in 2010, spent more than 50 years working at the University of Pennsylvania Medical School and created the well-known acne drug, Retin-A. In 2021, however, Penn Medicine apologized for Kligman’s practices and discontinued a lecture named for him, renaming it instead for Bernett L. Johnson Jr., a prominent Black dermatologist who began working at Penn in the 1980s

The City of Philadelphia also apologized for Kligman’s transgressions in a statement released in October.

“Without excuse, we formally and officially extend a sincere apology to those who were subjected to this inhumane and horrific abuse,” Mayor Jim Kenney said, The Inquirer reported. “We are also sorry it took far too long to hear these words.”

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku and Android TV. Also, please download theGrio mobile apps today!