WASHINGTON – When Lisha Quarles found out her son, Mannin, was shot and killed on a corner in the nation’s capital this year, she knew what the ensuing narratives would be. He was a criminal. A nobody. A man who got what he deserved. And then the most painful assumption – he wasn’t even raised right.

Mannin was in the Southeast area of Washington with friends on Sept. 1 when a man came up to the group, according to Quarles and others familiar with the incident. There was a fistfight, and then the man pulled out a gun and shot 32-year-old Mannin.

“Everybody knows who did it. They’re just not telling anything,” Quarles said. “I still don’t know why he went up to my son.”

Mannin’s friends and family loved him so deeply. That’s part of what drives his mother into deep denial sometimes. “You’ll never be able to heal from it,” Quarles said, fighting back her tears. “You just try to cope [with] it. Every night I cry. I be walking and just want to bend over and scream and cry. It’ll never go away. I can’t sleep at night. I keep trying to tell myself it’s not real, but it is.”

The insinuation that Quarles failed in parenting her son intensifies her pain. “I hear people say that parents need to raise their kids better. I was a single, poor mom, and I did the absolute best I could,” she said. “Mannin never grew up to shoot and kill anyone. He loved people, he loved God, he loved life. I feel like God wanted my son more than he needed to be here, but he didn’t have to go out like that.”

Deaths like Mannin’s, along with other violent crimes are increasingly common in D.C. now. As the rest of the country experiences almost a 10% decline in shootings and murders since 2022, Washington, D.C., is in the midst of a public safety crisis that has local leaders, residents, law enforcement and politicians scrambling for answers and wondering why violence grips their city.

In a miasma of finger-pointing, admitted complacency and silence – because not one city or police official responded to numerous requests from theGrio to discuss the city’s surging crime rate – residents of Black areas experiencing upticks in murders and carjackings are talking about why they’re seemingly on their own.

“It’s a combination of things,” said Tyrone Parker, a community leader in the city. “We have a unique situation where individual agencies are not working on the same page. [Our city] is not listening to people on the ground. It doesn’t have to be this way.” A lack of coordination and a smaller police force, among other departmental changes, all have contributed to the crime surge, community leaders and other residents have said.

Among the 25 largest cities in the country, Washington has one of the highest increases in homicides from 2022 to 2023. Cities such as Philadelphia, Atlanta, Los Angeles and Pittsburgh all have 20% decreases or more in homicides.

As of Nov. 8, Washington homicides are up 33% compared with the same date last year, violent offenses are up 39% and property infractions have jumped 25%. Crimes vary, from seven people dying during one weekend in separate shootings to five people getting shot in a single rampage. Other days saw four brazen gunmen popping out of a car and robbing a group leaving a swanky restaurant and a teenager racking up nearly two dozen charges related to carjackings dating back to May.

“The most pressing concern that I have heard from community members is the increase in robberies and carjackings and the fear that this creates,” acting Police Chief Pamela A. Smith said during her September confirmation hearing.

Much of the violence is concentrated in poor, Black neighborhoods. The city is composed of wards. Wards 7 and 8, both 86% Black, experience the most homicides and assaults with violent weapons. Half of the people in Ward 7 earn less than $50,000 a year and the largest percentage of people make less than $15,000 annually. The stats are the same in Ward 8.

The age of suspects and the ease with which they get weapons concerns the community. “Some of these shooters are 12, 13 and 14 years old,” said the Rev. Donald Isaac, a local clergy leader. “Guns are readily available. People are selling guns in the neighborhood the way they used to sell drugs.”

During her confirmation hearing, Smith made the same observation about young people and violence. “I am committed to working with families in neighborhoods and community and government partners to engage with youth to keep them safe and deter them from getting involved in crime.” But she didn’t elaborate on her plan, nor did she return theGrio’s calls and emails seeking details.

The current deadly chaos didn’t happen overnight, residents said. There had been a steep decline and then a lull in crime on Washington’s streets. But then years of complacency mixed with diminishing coordination between cops and community along with a shift in police priorities — it’s all come to a murderous-carjacking-stay-in-your-house head. “Our problem is not a lack of resources,” Isaac said. “There just needs to be better coordination of those resources.”

Things got good, people got comfortable

In 2012, Washington had 88 murders. The District of Columbia had come a long way from the 489 killings in 1990. “We are on course now to have the lowest number of homicides since 1960,” then-Mayor Vincent Gray said at a press conference that year.

Like the current crime surge, the low murder rate in 2012 didn’t happen overnight. Proactive police work and synergy between the police and the community produced that success.

Anthony Motley from Ward 7 was born in the ’40s and returned to his neighborhood to do community work after a military stint. He remembers the ’90s with each year logging more than 400 homicides, most committed with a gun. “The city was in bad shape,” he said, “and we all knew something had to be done.”

In 1993, he and other religious and community leaders started Redemption Ministry. “We went to the streets from 8 p.m. to 2 a.m. at least once a week in different neighborhoods,” he said. “We tried to target 17 neighborhoods in our communities that were hotspots.”

Redemption Ministry then collaborated with the Metropolitan Police Department’s East of the River Clergy-Police Community Partnership. “Clergy, community partners and the police went to the table to figure it all out,” Motley explained. “We all sat down at the table once a week, and we all talked about our experiences, successes and failures. The police were there too.” Clergy members joined police in identifying kids who were taking risks and heading toward committing offenses and redirecting them into productive, legal activities.

Ronald Hampton, a city police officer from 1970 to 1994 and a previous executive director of the National Black Police Association, remembers police and residents working as a team.

“It was always communication. People were talking. Police officers walking the foot beat talked to the citizens,” Hampton said. “I lived on my foot beat.… There was a network of people talking. That was lost, and we haven’t done anything about reestablishing that network.”

Hampton, Motley and others all agree that community-law enforcement coordination made the city safer and drove down violent crime. “We had a police chief who was friendly and understanding,” Motley said, referring to former Charles Ramsey, the first Black chief of the Metropolitan Police Department, who served from 1998 to 2006.

Ramsey initiated relationships with community leaders. “He called and asked to meet with all of us. We always spoke with him,” Motley said. Ramsey expanded community policing efforts that became a model for other cities. He formed a more accountable organizational structure within the agency and improved recruiting and hiring practices. Ramsey’s leadership and community efforts produced results. During his tenure, there was a 40% drop in the city’s crime.

“We had a real partnership with the department when Ramsey was the leader,” Isaac said. “We had police partners that would tell us there were beefs, and they would try to get us to help negotiate a truce.”

Today, that coordination doesn’t exist.

“What happened was politics,” Motley said. Adrian Fenty became Washington mayor in 2007 and he hired Cathy Lanier to replace Ramsey. “Adrian Fenty ceased communications and since then the mayors haven’t been as cooperative,” Motley said. And since crime numbers kept dropping, even the community became a little complacent about engaging with police.

“I think people saw the numbers in 2012 and thought it would just stay like that,” Parker said. “But many of us were trying to get in touch with the [mayor and the police department leadership] to see if we could work together to get the numbers even lower, but those meetings never happened.”

Groups focused on addressing violent crime worked on their own, residents and community leaders said. The tumult of the COVID-19 pandemic and George Floyd’s murder illuminated just how entrenched and ineffective the siloed attempts to address crime had become.

Washington has multiple city-led violence prevention and intervention programs, but “when you talk with the citizens, they don’t know about the programs,” Hampton said. “They don’t know how to access them.”

Brothers standing in the gap

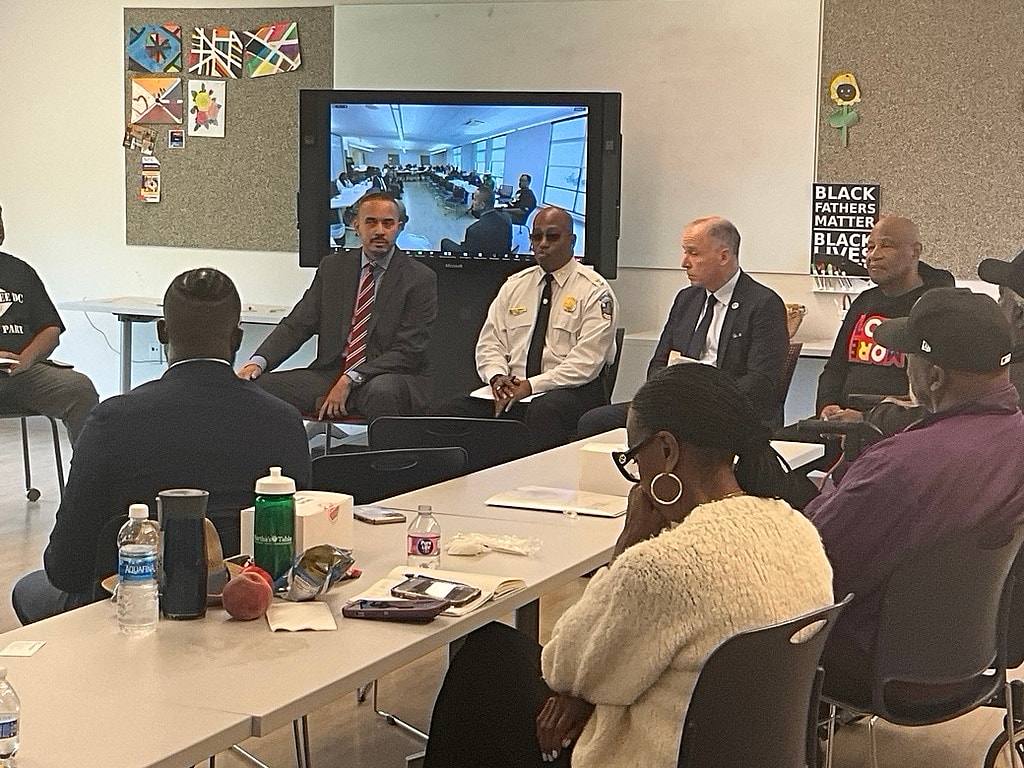

On Sept. 26, local leaders met with representatives from the attorney general’s office, the police department and the mayor’s office. During the meeting (of which theGrio obtained video), the community members respectfully pressed agency leaders about more coordination.

The responses were inscrutable and lacked specificity. Here’s what they said:

Nina Albert, acting deputy mayor for planning and economic development, replied, “A lot of what we’re trying to do and what I’m trying to do is strip back to the basics because in the size and graph and scope of what you describe as a $20 million government…the basics are how do we keep you alive today and what do we do.”

The mayor’s office did not respond to multiple requests seeking an explanation of Albert’s response and specifics on how that office plans to coordinate with community leaders and programs.

The response at the meeting from Andre Wright, the assistant chief of the police department’s Youth and Family Engagement Bureau: “We are 24 hours, 7 [days] a week, 365 days a year agency, and all of the government agencies lean on us, and we lean back on them.” Without explaining how or why, he also said the bureau’s relationship with the community has diminished since he began working there. “The [police department] will be most effective when we get back to dealing with young folks and enhancing that relationship” he added.

The Police Department did not respond to multiple requests for comment by theGrio asking officials to explain how it plans to enhance and restore community relationships. Asked about the seeming lack of community collaboration, a spokesperson for the department referred theGrio to the confirmation hearing video for Smith, now the police chief.

Brian Schwalb, the attorney general for Washington, D.C., didn’t respond at the meeting regarding coordination. The Attorney General’s Office, which employs Schwalb, did not respond to multiple requests for comment by theGrio. The district lacks a local court system. Its local court is the federal court and prosecutes the cases from the city’s Metropolitan Police Department.

The residents who set up the meeting have decided not to wait for the restoration of a community-cop relationship. They have started a new coalition of community leaders to address public safety known as CREWS (Communities Respecting Everyone’s Will to Survive).

The group consists of local activists, clergy members, organization leaders and concerned residents. Every day, they try to send four to five men onto the streets as a resource for people who want escorts as they walk to school or grocery stores. And they try to establish relationships with people suspected of being involved in criminal activity. CREWS meets weekly to hold itself accountable for its efforts.

On Oct. 11, they convened at the office of the Alliance of Concerned Men in Ward 7. Parker, a community leader, co-founded that organization in 1991 to combat youth crime, and he continues that effort in his retirement.

Members of the group, mostly men 50 or older, exhibit deep respect for one another, referring to every man as “brother.”

They’re passionate. While discussing how to plan events to raise awareness about their services, a brother banged his hand on the table to declare, “Whatever we do, we just gotta come together and motivate each other. We need everyone’s support.”

And they’re funny. After settling on purchasing T-shirts with the group’s insignia to help residents identify CREWS members, one member jokingly objected, “We out there in the cold. So a T-shirt ain’t gonna do nothing for us. We need hoodies and we need a skull cap.”

With a consensus on warmer clothing, they brainstormed meeting basic community needs such as groceries and school supplies and how to put an end to people using bus stops as social gathering locations. And there was a pointed question: “Why aren’t the police here?”

Pointing fingers and calling bullshi*t

There’s a national debate on whether calls in 2020 to defund the police contributed to the city’s crime surge. The district responded swiftly to that demand. In June 2020, the City Council announced that it would cut $15 million from the police budget. Those funds went to city agencies that address neighborhood safety engagement, eviction assistance, justice grants and victim services. The overall budget for 2021 ended up being $545 million, $14 million less than for 2020.

Additionally, during the last three years, more than 450 officers left the department. The Washington police union chairman, Gregg Pemberton, contends officers bolted in droves as the city passed policing reforms that included: prohibiting neck restraints, improving the use of police body camera footage, reforming the office of police complaints, limiting consent searches, improving minimum requirements to become a police officer and limiting the use of chemical weapons and riot gear.

“We are about to have our third year in a row of 200-plus homicides, robberies and carjackings are out of control,” Pemberton said, “and the Council seems laser-focused on driving good officers out of the department.”

Hampton said it’s “bulls**t” that there’s anything in the 2020 legislation that would stop police from doing their job. “There’s nothing in there that would prevent me [a 24-year member of the city police force] from doing my job as a police officer. You need to go out and do your job and you need to do it legally and constitutionally.”

Crime data seems to align with Hampton’s assessment. Officers have been leaving the department for the last three years, but there was also a decline in crime during some of those years. There was a 10% drop in homicides in 2022. Similarly, violent crime declined by 7% in that time frame. Those statistics suggest police reform and fewer officers might not have contributed to the 2023 crime spike.

Some politicians and city residents said the U.S. attorney’s office is not prosecuting a large number of cases related to arrests the Washington police make, and that might be a reason for the crime surge. A local news station reported that the typical person charged with homicide usually has 11 prior arrests. That prompted Rep. Jake LaTurner (R- Kan.) to press a representative from the U.S. attorney’s office to disclose how many people charged with murder were previously arrested for violent crimes but not prosecuted. He was unable to answer.

The dissension about leaving criminals on the streets, police chiefs not emphasizing community collaboration and officers quitting because they can’t use some restraint or search tactics anymore – none of it addresses the murders and the carjackings.

“One of the things that really causes me concern is that everybody wants to throw daggers at one another rather than sit down at the table and figure this out. We’re all supposed to be in this thing together,” Anthony Motley said.

The finger-pointing ignores what people like Curtis Mozie see in his community every day.

Mozie, also known as C-Webb, has been documenting gun violence in the city since the late 1990s. He goes around the city with his video camera to speak with victims and relatives of those who have been killed. He wants to get the perspective of those in the neighborhoods.

He’s done so many interviews over the years that he’s connected with different generations of the same families. “Kids who lost their dad at a young age want to come to watch my videos to see if I have footage of their father,” Mozie said. “A lot of times I do have footage of them.”

His office, known as “C-Webb’s Safe Space,” is in Ward 5. It’s a spot where the youth can hang out without worrying about whatever their troubles are on the streets.

People can view C-Webb’s footage in his studio. The videos include kids talking about losing a brother, uncle, cousin, or friend to gun violence. They discuss their neighborhoods, what they see every day and the hope they have for a better future.

There’s a memorial wall opposite the television screen. It shows dozens of photos and names of people C-Webb knew who were shot and killed. It goes all the way back to 1982. Red roses and police tape adorn the wall. Most couldn’t fathom losing that many people. C-Webb barely can.

“Gun violence is treated as a normal part of life for us,” he said. “I just hope we can get to a place where we don’t have to live like this.”

Correction Nov. 13, 2023 11:22 a.m. ET: An earlier version of this story incorrectly identified Brian Schwalb’s employer. The story has been updated.

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku and Android TV. Also, please download theGrio mobile apps today!