TheGrio Green Book is a modern-day twist on the historic African American Green Book, which guided Black travelers to welcoming and safe places across the country. We continue this tradition with hope, joy, and the will to explore places that were once only dreams for our ancestors—or where our diasporic roots run deep. These are our tips, reviews, and advice for #TravelingWhileBlack.

Tucked along the water in the lowcountry of Hilton Head, South Carolina, the land that Black American rebels once walked is still growing green grass.

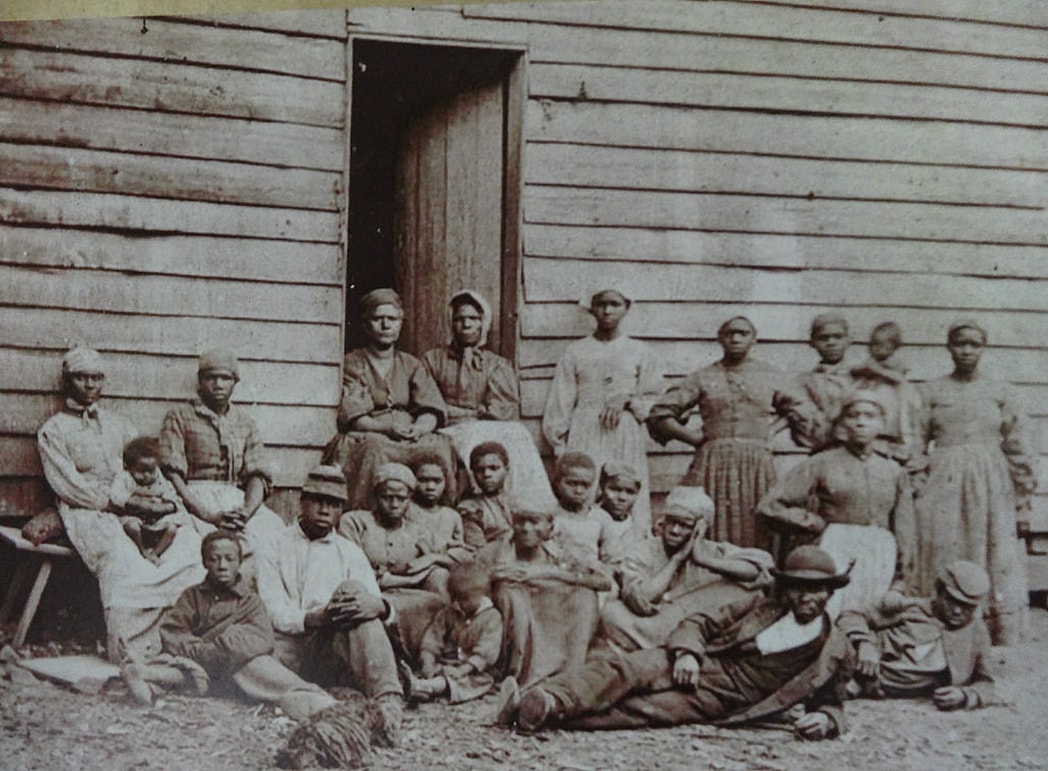

The sacred ground is called Mitchelville Freedom Park, and it was once home to Black residents who were technically “illegal” in the eyes of a changing America. They were considered contraband– “products” of war.” Merriam Webster defines “contraband” as “goods or merchandise whose importation, exportation, or possession is forbidden.” These human beings, Black, American and formerly enslaved, were not supposed to be walking free. But with the end of the civil war, they were looking for home. As white masters and plantation owners fled for their lives, thousands of formerly enslaved Black people sought out the Union Army’s headquarters in Hilton Head.

They imagined life anew, willing to get their hands dirty to work, build and fight for their freedom. The “refugee barracks,” as they were called, were no paradise or utopia and rife with struggle, and even some abuses, including the assault of Black women by white troops. After reports made their way north to the US Secretary of Treasury, the government sent staff and workers to start schools and “freedmen’s aid societies,” an initiative which would become known as the Port Royal Experiment.

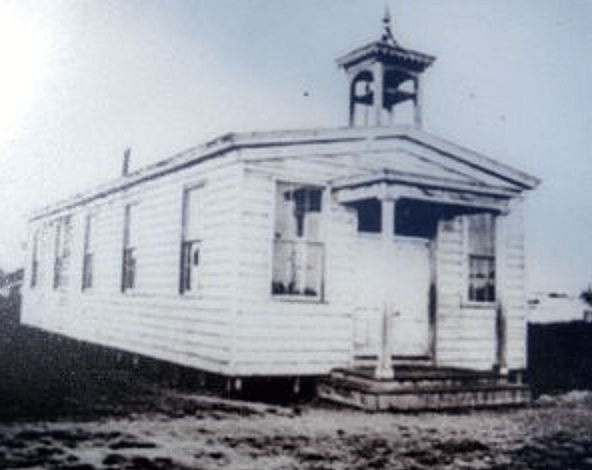

They would start their own church, the First African Baptist Church. And when Union Army Major General Ormsby Mitchel, an abolitionist took over the government’s command of the area, it would eventually be named Mitchelville in 1862 after him, just one year before the Emancipation Proclamation was signed by President Lincoln.

“His father had owned people and told him that that was the worst mistake he’d ever made. It goes against anything they should believe in and pressed upon him to not do that,” says Ahmad Ward, Executive Director of the Mitchelville Freedom Park.

“He sees what’s happening with people and he has this flash–that he would give people 300 acres of property and say this is your land, you build on it, you grow things, you create schools and churches and businesses. It’s a chance for you to govern yourselves.”

Mitchelville would end up becoming the first official self-governed town of Black freedmen in the United States that we know of, where Black politicians and town workers called the shots. According to historians, Mitchelville put into place the “first compulsory education law in South Carolina” and wrote into law that any child age 6-15 must learn in school.

These residents were special not only because of their self-governance but because of their Gullah Geechee heritage, a rebirthed culture derived straight from Africa, preserved in the lowcountry because of its geographic isolation.

Far from being lost or looking for a handout, history tells us that Black residents of Mitchelville stepped right into their God-given rights of self-determination and civic engagement.

(Photo courtesy of exploremitchelville.org)

“Remember, these were the same individuals on whose back this country was built,” said Shirley “Peaches” Peterson, who served as Chair of the Mitchelville Preservation Project in a TEDx talk about the town. “Many of the former slaves could read and write. They had skills—they were blacksmiths, they were carpenters, cooks, caretakers, seamstresses, herbalists or the early doctors of the time.”

“Mitchelville speaks to the value of the opportunity for citizenship.”

Despite that thriving citizenry, Mitchelville’s story came to an end in a combination of catastrophes– a hurricane in 1893 devastated the land, breaking open a wave of disputes over deeds and ownership of various properties.

Mitchelville’s land, which once was The Drayton Plantation, would be given back to the heirs of the plantation’s family, who then broke it up and ironically sold it to multiple Black families, sparking another years-long dispute.

What once was a thriving town of 3,000 would dwindle to 300 people through the complex tapestry of time passing.

Mitchelville would eventually be developed as Mitchelville Freedom Park—a tourist site that boasts sculptures and structures that reflect the town which once stood there, including the First Baptist Church which was dug up from the ground to be revealed. There is an impressive bronze statute of Harriet Tubman that greets you upon entering, and as visitors walk along the grassy plains where Black Mitchelville families once lived, they can run into the Toni Morrison bench, placed there by The Toni Morrison Society. The park also has annual events such as a Juneteenth celebration, complete with music and performances.

So why don’t more people know about Mitchellville?

The answer likely reflects the struggle to reckon with all chapters of America’s true history that we see playing out in multiple places.

The leaders of Mitchelville Freedom Park are trying to change that by leading a major capital campaign in hopes of raising enough funds to keep renovating the land into a place to draw new visitors, building an archeological research facility while preserving what’s left of the town’s past.

At a time when American history is being vigorously debated, Mitchelville is a story that could seemingly unite both sides of the political spectrum. These residents were Black American patriots who poured into building an American town anew, despite the torture and degradation they experienced during slavery. Their descendants still walk the land today.

The urgency and power of knowing Mitchelvile’s story could inspire a generation to imagine their thriving nation again, even after painful and violent chapters.

In a speech that Major General Ormsby Mitchel gave at Mitchelville’s First African Baptist Church, he said of the town’s Black residents: “Give him the earnings of the sweat of his brow, and as a man, we will give him what the Lord ordained him to have.”

“It seems to me a better time is coming … a better day is dawning.”

In making a visit to Mitchelville Freedom Park today, look out on the water that Black rebels once walked on, you may see that dawn for yourself.

Natasha S. Alford is the Senior Vice President of TheGrio. A recognized journalist, filmmaker, and TV analyst, Alford is also the author of the award-winning book, “American Negra.” (HarperCollins, 2024) Follow her on Twitter and Instagram at @natashasalford.