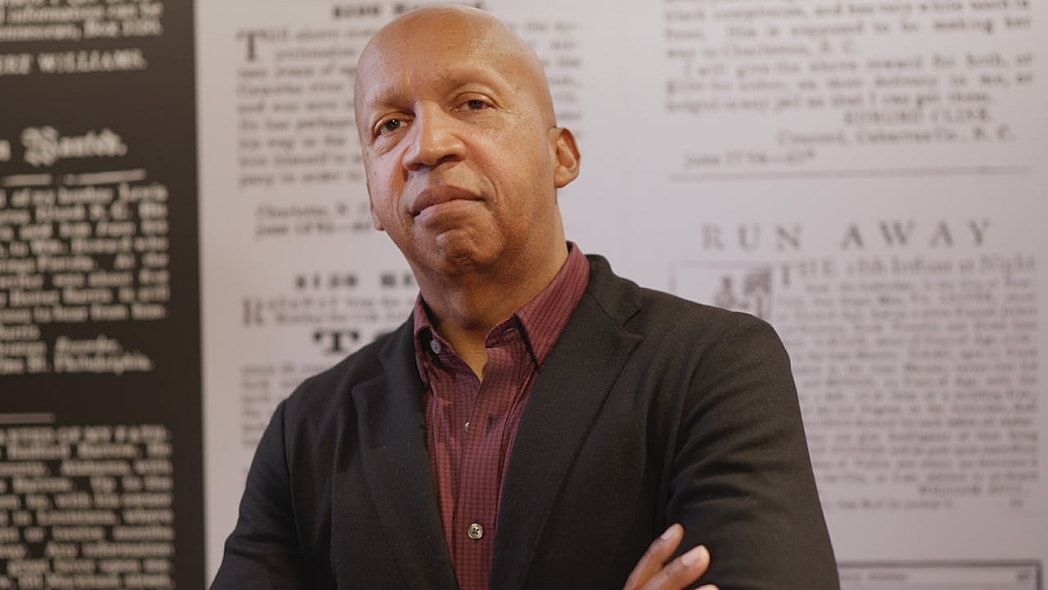

Acclaimed defense attorney Bryan Stevenson has about 10 million new clients on his roster.

While you may remember him as the subject of the film Just Mercy, played by Michael B. Jordan, a Harvard Law graduate turned lifesaver who got clients off death row, Stevenson’s need to get to work isn’t driven by his résumé.

His expanded client roster is more spiritual than literal. Rhetorical rather than contractual.

In Stevenson’s mind, these clients never got the just mercy they were due, and it’s his mission to make it right.

“I feel like I’m now representing the 10 million Black people who were enslaved for 246 years who endured hardship, immense suffering, and constant sorrow,” Stevenson told theGrio in an exclusive interview in Montgomery, Alabama, in January. “I think they need an advocate when people are trying to erase their pain and suffering.”

That erasure is the biggest story of our nation in this moment.

History exhibits tied to Black culture are being removed at the request of the Trump administration. Edits to accepted facts are being made, most recently in Mississippi, where the Trump administration has asked the National Park Service to remove references to racism in an exhibit about civil rights leader Medgar Evers, who was killed by a Klansman as he stood in the driveway of his home.

“We’re at a moment where the politics of fear and anger are raging. And when people allow themselves to be governed by fear and anger, they start tolerating things they should never tolerate. They start accepting things they should never accept.”

While there is a collective mourning throughout Black America, coupled with outrage over the insult to memory and the historical record, Stevenson has created his own sacred grounds, where Black history is preserved and protected.

They are called The Legacy Sites, and they are a group of three sacred grounds in Montgomery dedicated to telling the unvarnished story of racial injustice and Black resilience in America: The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, the Legacy Museum, and the Freedom Monument Sculpture Park.

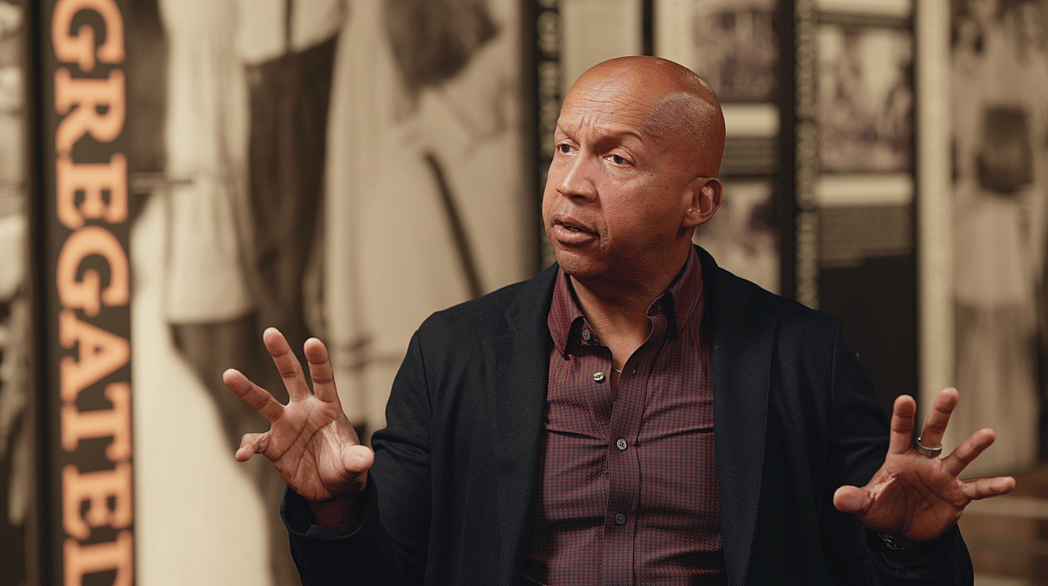

“We realized we were going to have to continue our legal work, but also get outside the courts and start doing this narrative work. The work we’re doing here in Montgomery is a manifestation of a commitment to engage narratively with the history of America — the identity of America.”

Before I could even sit with Stevenson, it was required homework to visit the sites to understand his work, which he calls “narrative work” — a mission so powerful, it seeks to right a wrong in America that existed long before the anti-diversity era led by the Trump administration.

“The people who enslaved other people didn’t want to think of themselves as immoral or unjust. So [they] created a false narrative — that Black people were less worthy, less human,” Stevenson tells theGrio. “That narrative is what survived the Civil War. It’s what continues to create many of the issues we are dealing with today.”

Stevenson points out that while many countries, like Germany and South Africa, removed relics of the past that celebrate abusers and murderers, in the United States, Confederate monuments are openly preserved — the Confederate flags of red with starred X’s being some of the last images that Black people saw before they were lynched or burned to death.

Inside The Legacy Sites, that terror and brutality are front and center, contextualized for all to see and understand.

At the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, a sprawling six-acre park on a hill, visitors slowly ascend toward molasses-colored monuments of steel, greeted by hints of the stories they will encounter at the top.

The kidnapping and brutal exploitation of slavery, embodied in a sculpture of chained African victims, one mother holding a baby and screaming in terror, is placed at the entrance.

Once you reach the top of the hill, you get close enough to see that each corten steel rectangular structure has a single county listed, and below it, the names of all the victims of lynching in that county.

Some of the most haunting contain unknown names, but here on the Legacy Sites’ hallowed ground, they are counted. Visitors realize that as they walk down into the site, the steel monuments start to suspend over their heads, and their heads tilt up in the same way witnesses of a lynching would to see bodies swinging above them.

Inside the Legacy Museum, visitors start with a haunting and sobering sight — a tribute to enslaved ancestors who perished in the ocean, with lifelike sculptures spread across the sea’s bottom and the sound of waves crashing, booming through the speakers.

The museum smoothly transitions from era to era, weaving a story of how slavery morphed into Jim Crow and lynching, providing firsthand accounts of what people witnessed and stated. Medium-sized jars contain soil from the grounds where Black victims were lynched and took their last breaths.

There are quotes displayed on walls that explain the extent of the hatred Black Americans encountered simply in trying to live their daily lives:

“In this state we are committed to segregation by custom and law; we intend to maintain it,” one grand jury wrote.

The quotes also show Black Americans speaking for themselves about what they endured:

“To be a man and not to be a man, a father without authority, a husband and no protector, is the darkest of fates. Such was the condition of my father and such is the condition of every slave throughout the United States. He owns nothing, he can claim nothing. His wife is not his. His children are not his. They can be taken from him and sold at any minute…,” wrote John S. Jacobs, who was enslaved as a child in North Carolina.

Stevenson says these quotes and displays are intentional and meant to challenge some of the whitewashing of slavery, as well as more sophisticated arguments about why learning about the past is allegedly divisive or not even necessary.

“This is not new — during every era of our history, the response to ending slavery was, ‘Oh no, it’s fine. The enslaved people, they’re happy. This is good for them. We don’t hate them, we’re taking care of them, and it’s you abolitionists that are stirring things up, that are creating problems.’ There’s always a counter-narrative to basic human rights and basic dignity.”

It’s a powerful statement that Stevenson is so well-regarded and well-organized that he has been able to independently fundraise and sustain the operations of the Legacy Sites, which bestows a narrative freedom to him that not all museums have.

No one person can tell him to remove an exhibit, nor soften the truth.

As I mentally prepared myself for what I expected to be complete heaviness paired with grief while walking through the Legacy Sites, I found myself encountering something else — hope.

The Legacy Sites are intentionally designed with testimonies of resisters and revolutionaries. In fact, what better land to host these museums and sacred sites than on the same ground Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., John Lewis, Rosa Parks, and Claudette Colvin once marched on.

At the new Elevation Convening Center and Hotel, which officially partners with the Legacy Sites, visitors can look down the famous road where protesters marched.

Their struggle for rights and freedom is why Stevenson says he won’t stop working — both for the 10 million ancestors who endured unspeakable pain and for those who gave their lives securing justice for all.

“I’m going to represent the 50,000 Black people in Montgomery in 1955 who chose to stay off the buses by creating a Montgomery that honors their struggle and sacrifice.

“When you take on a relationship like that to history, I think you feel like you’re ready to go. Like you’ve got to push, not that you can give in to fatigue. And yes, it’s challenging and exhausting and unfair — it’s all of those things. But that is both the burden we must overcome and the opportunity we have to contribute to a future where people don’t have to be tired by the challenges that have been created for us.”

Watch the full Masters of the Game episode with Bryan Stevenson tonight at 8pm ET on Grio TV and 9pm ET on YouTube.

Natasha S. Alford is an award-winning journalist, author, and media executive, currently serving as Senior Vice President and Chief Content Officer at theGrio. She is the author of American Negra, an International Latino Book Award–winning memoir. Follow her at @natashasalford across social platforms for the latest.