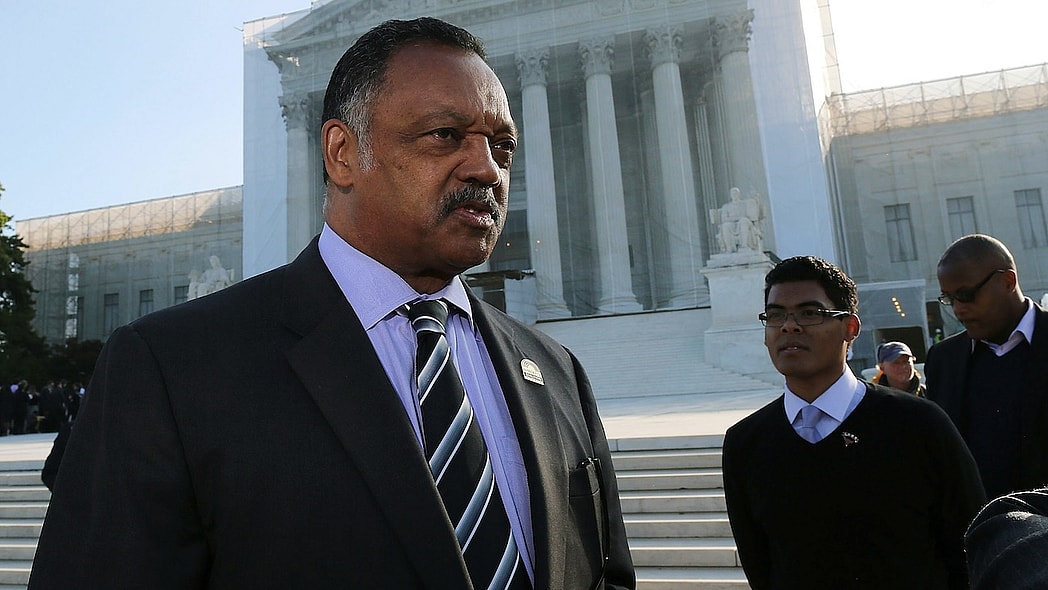

As racism continues to be more pervasive and more dismissed every day, we must now also mourn the loss of one of its biggest fighters, Rev. Jesse Jackson. While historians and politicians will no doubt have a lot to say about his significance, I am mindful of the importance of remembering the deeper meaning of his words, especially regarding our mental health.

Although Rev. Jackson was never formally trained in psychology, his messages challenged Black individuals, families, and communities, ensuring that they knew who they were in the face of racism so they could make themselves and their society a better place. As a clinical and community psychologist working with Black children and families, I know that the psychological benefits of knowing and understanding a culture’s significance are critical.

That his loss comes during the recognition of 100 years of Black History celebrations only cements how important understanding the self is to our ability to withstand the daily onslaught of negative messages about who we are, especially from a president intent on dismissing the past from reality.

This reality, in which Dr. Carter G. Woodson—only one generation removed from slavery—established Negro History Week to remind this country of our contributions, deserves to be recognized. In 1976, this week was extended to Black History Month. Yet, 50 years later, we are now observing active erasure of that history, current opportunities, and future growth of Black Americans and other Americans of color nationwide.

Dr. Woodson and Rev. Jackson were both adamant about ensuring that Black achievement would live on in this country. Rev. Jackson’s words extend this education, pushing us to fully realize the crucial role of one’s psychology in Black wellness. He taught us how, in the face of adversity, we must know who we are, as individuals and as a people, both now and in the future:

“I am – somebody.”

Having a sense of agency and knowing who we are as individuals, even in the most difficult of circumstances, helps us to persevere. Fighting back ensures that our voices are heard. Today’s generation of young people has kept Jesse’s torch lit, showing how activism can be psychologically supportive of their sense of agency and reduce clinically meaningful depressive and anxious symptoms. My colleagues and I continue to find that the more agency Black youth embody regarding racism, the better their psychological outcomes.

“It is time for us to turn to each other, not on each other.”

As a communal people, we must work collectively to strengthen our psychological well-being and activism. While this time may feel politically fraught, recalling that some of our greatest mental health assets come from interdependence and kinship reminds us of what collaboration affords us. Whether in church basements, on Black Twitter, or on the streets during a protest, re-membering—coming back together and forming a larger force—is what gives us the victory.

“Keep hope alive.”

Hope may seem like a simple tool. Yet, it is critical to the story of Black American persistence and resistance in the face of such unknown futures. And the research bears this out, too: across historical events (such as the Holocaust) and across various fields (such as medicine and law), hope remains a significant factor in positive outcomes both during the traumatic event and after. Hope provides physiological and psychological benefits that very literally change our body and brain’s way of perceiving what is possible – what our future can hold.

How will we remember our past to shape our future?

We cannot forget our history. We must maintain the progress of the present. And we have to advance the science of the future. We have to keep Rev. Jackson’s words at the forefront to reinforce our community, our ancestry, and our perseverance, and to remain more resistant to the ongoing attacks on our heritage and history.

We celebrate 100 years of Dr. Woodson’s vision by preserving what actually makes our country so great–recognizing individuals like Rev. Jesse Jackson for their courage in the face of racism, reinvesting in programs and policies that work towards redressing historical and contemporary racism, and ensuring that Black youth—both now and in the future—know that they are somebody.

Dr. Riana Elyse Anderson is a licensed clinical and community psychologist, associate professor at Columbia University’s School of Social Work, and affiliate with Harvard’s Hutchins Center for African & African American Research and FXB Center for Health and Human Rights. She is a Public Voices Fellow of The OpEd Project in Partnership with the National Black Child Development Institute.