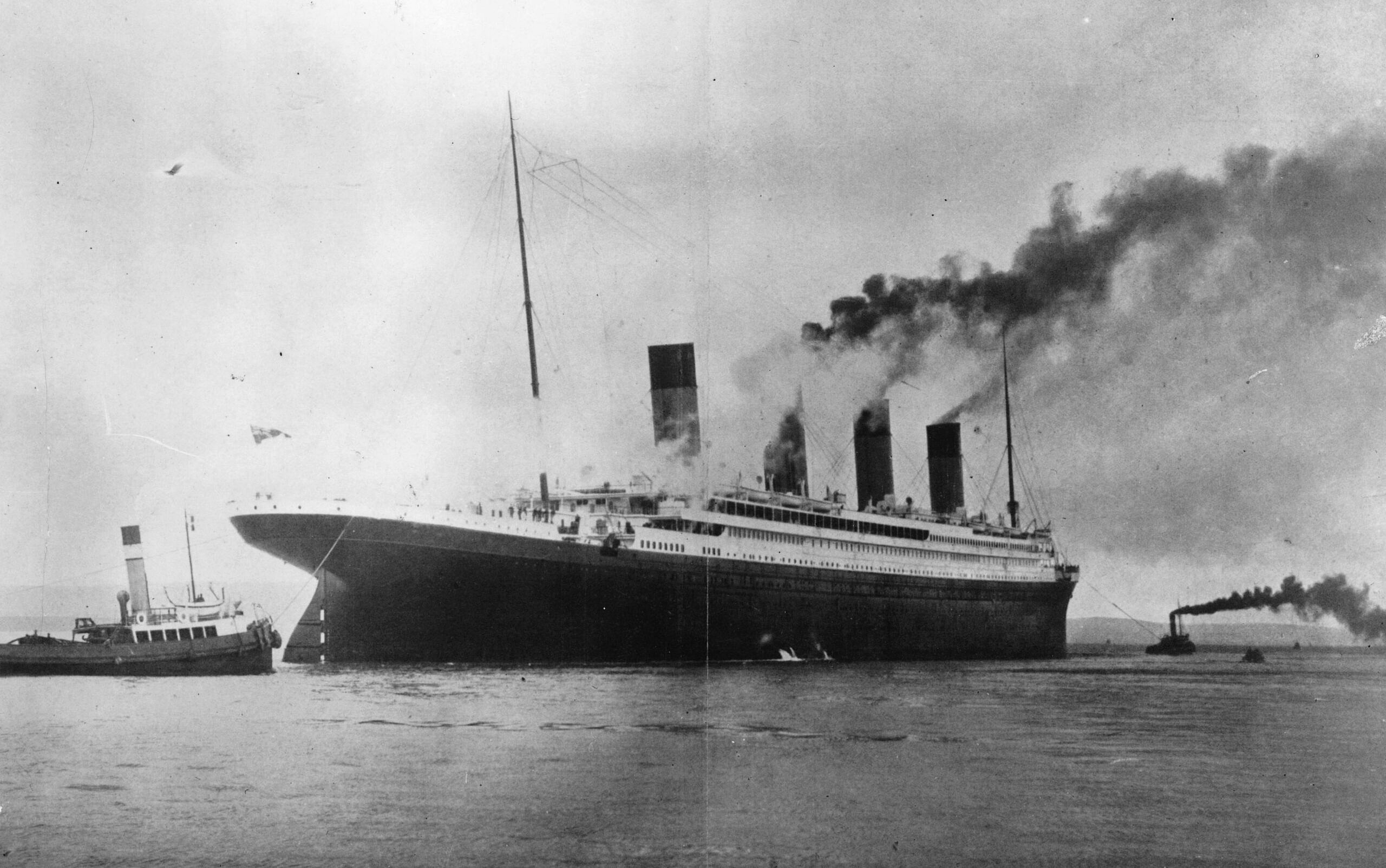

From Walter Lord’s 1955 bestseller “A Night to Remember” to James Cameron’s 1997 blockbuster, the story of the ill-fated RMS Titanic has captured the fascination of millions since the tragic incident claimed the lives of nearly 1,500 passengers in 1912.

We all know this story well; a steamship renowned for her speed and luxury ignored ice warnings on her maiden voyage and struck an iceberg — sending socialites, refugees and a real-life Jack Dawson to early graves.

While Titanic’s sinking has become one of the most infamous shipwrecks of all time, the story of the only Black family aboard has largely been excluded from history.

READ MORE: Coronavirus traces lingered on cruiser for 17 days after evacuation

Joseph Philippe Lemercier Laroche, 25, was a Haitian native traveling as a second class passenger on Titanic. He accompanied his pregnant wife and their two daughters, Simonne and Louise, on the ship’s maiden voyage.

Born into a prosperous and powerful family on May 26, 1886 in Cap-Haitien, Haiti, Joseph was the nephew of Haitian president Dessalines M. Cincinnatus Leconte.

As a child, he took an interest in engineering and was sent to study in France at the age of 15. While visiting a tiny French village several years later, he met Juliette Lafargue, his future wife. After earning an engineering degree, he turned to the Parisian job market.

Joseph was a skilled professional with a degree. He was fluent in English, French and Creole. He came from an affluent family who paid for his education. But he was still a Black man living in 20th century Europe. Racial prejudice and discrimination created an insurmountable barrier that left him struggling to find adequate work. With a growing family and little opportunity for him to provide for them in France, Joseph and Juliette decided to return to Haiti in 1912.

Overjoyed with the news of the family’s return, Joseph’s mother bought them first class tickets on the French liner La France as a reunion gift. However, due to conflicting accommodations that would’ve left the young parents without direct access to their children, the Laroches exchanged the tickets for second-class reservations on the new White Star Liner RMS Titanic.

Neither Joseph nor Juliette could possibly have anticipated the tragic complications of this decision.

The Laroches boarded Titanic on April 10, 1912 at Cherbourg. Over the next 3 days, they likely enjoyed several amenities afforded to second-class passengers — luxurious staterooms, a dining saloon, library and three outdoor promenade decks. In a letter addressed to her father and sent from Titanic’s final stop of Queenstown (now Cobh) Ireland, Juliette Laroche wrote of Titanic’s luxury and friendly fellow travelers:

The arrangements could not be more comfortable. We have two bunks in our cabin, and the two babies sleep on a sofa that converts into a bed. One is at the head, the other at the bottom. A board put before them prevents them from falling. They’re as well, if not better, than in their beds.

At the moment they are strolling on the enclosed deck with Joseph, Louise is in her pram, and Simonne is pushing her. They already have become acquainted with people we made the trip from Paris with a gentleman and his lady and their little boy too, who is the same age as Louise.

I think they are the only other French people on the boat, so we sat at the same table so that we could chat together. Simonne was so funny – she was playing with a young English girl who had lent her a doll. My Simonne was having a great conversation with her, but the girl did not understand a single word. People on board are very nice. Yesterday, they both were running after a gentleman who had given them chocolates.

There are conflicting and largely unconfirmed reports about racism experienced by the Laroche family and other non-white passengers onboard, but it is certainly feasible that they were the subject of stares, gossip and even crude remarks from crew members.

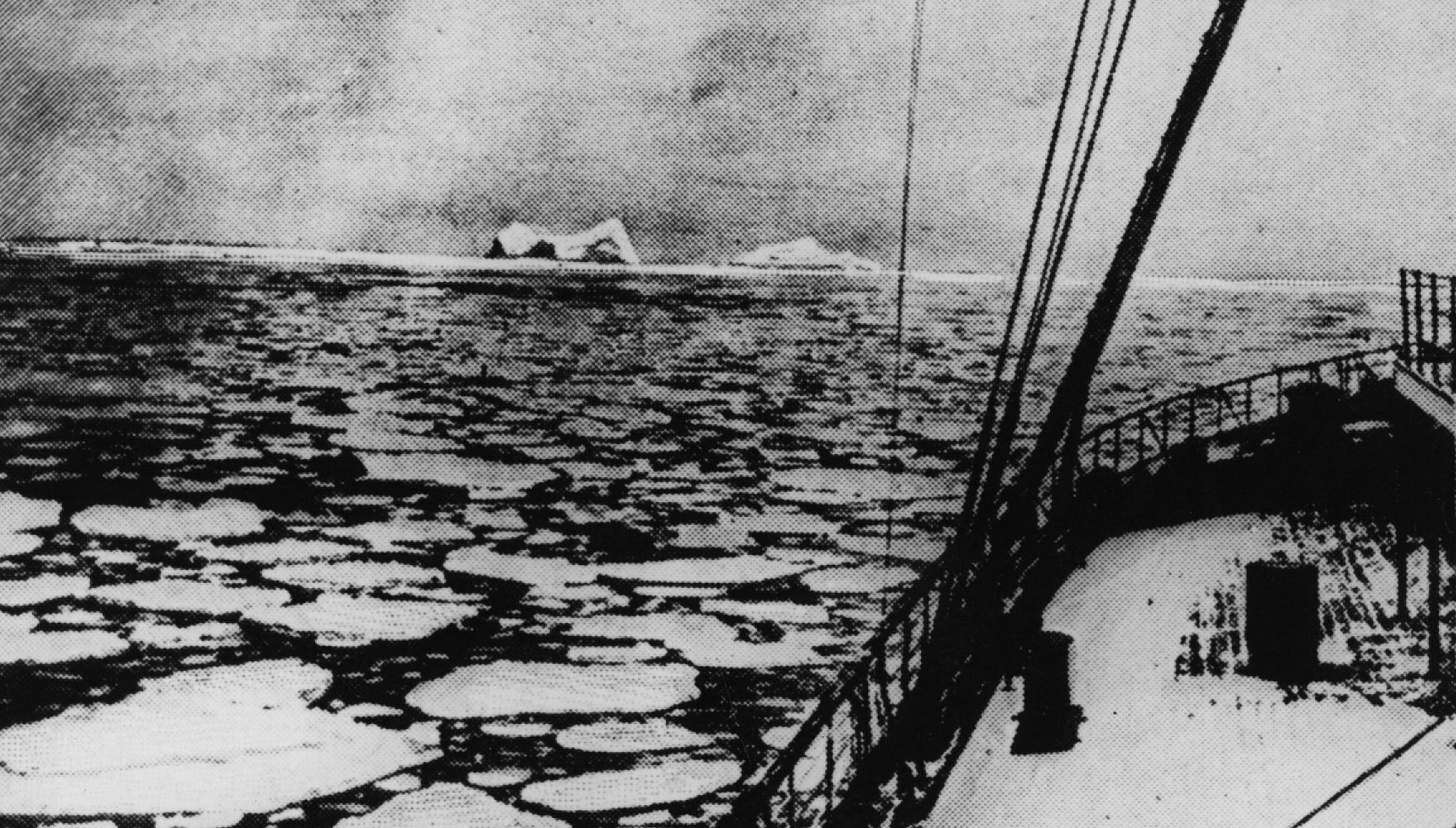

Nevertheless, their journey across the North Atlantic came to an abrupt end on the night of April 14. At this point in the voyage, Titanic’s wireless operators had received six reports of drifting ice from surrounding steamers, but she continued to travel at full speed.

Around 11:40 p.m., Titanic struck an iceberg 370 miles off the coast of Newfoundland. With only enough lifeboats for about half of its 2,200 passengers, the liner so famously described as “practically unsinkable” was ill-prepared for the circumstance, and the closest rescue vessel Carpathia was 58 miles away. Passengers were stranded in the middle of the ocean, with temperatures dipping below freezing and safety far off in the distance.

According to Juliette’s account, a steward woke the family and rushed them above decks to lifeboats. Juliette spoke no English, and was generally confused about what was happening. She followed her husband to the boat deck. Sometime after midnight, crew members were given the order to load women and children first. In the subsequent chaos, Joseph bid farewell to his pregnant wife and two daughters as they boarded Lifeboat 14, and promised that they’d be reunited in New York.

Joseph was never seen again. Little is known about his final moments. The Titanic sank just after 2 a.m. on the morning of April 15. Roughly 1,500 people were thrown into the icy waters beneath them as the ship broke in two and began its final descent to the ocean floor.

Juliette and her children were rescued along with 700 other survivors by the Cunard liner Carpathia several hours later. When they arrived in New York days later, they were met with crowds and reporters. They searched the masses in hopes that Joseph might’ve been rescued by another ship. Their efforts were in vain. Joseph’s body was never recovered.

The next several years proved to be tragic for the Laroche family. Juliette returned to France with her daughters, in grief. Later that year, Joseph’s uncle President Leconte was assassinated when an explosion destroyed the Haitian National Palace, just 4 months after the Titanic sank.

READ MORE: Honeymooners discover racist blackface ‘artwork’ on cruise ship

Juliette gave birth to a son in December 1912, who she named after his father. Joseph Jr. died in 1987. Louise, her last remaining child and the last French survivor of the sinking, died in 1998.

The story of the Laroche family is unique, but the erasure of their existence is all too familiar. The Laroches weren’t the only passengers of color on Titanic, but every mainstream effort to revisit the doomed ship’s past has excluded stories like theirs and others.

For years, many thought that people of color were barred from sailing on Titanic. Urban legends and tales from folklore added fuel to these theories, even compelling renowned poet Langston Hughes to note in a 1953 Chicago Defender article that as a child he, “remembered the old folks talking about it and how, ‘Thank God, there were no Negroes on that ship.”

It wasn’t until 1995, when a French member of the Titanic Historical Society interviewed Louise Laroche, that the remarkable story of the only Black family on the Titanic was first shared with the general public.

In the 25 years since, the Laroches have only been the subject of a few plays and a handful of articles. They haven’t been afforded the same kind of fame or name recognition as their white counterparts.

Joseph Phillipe Lemercier Laroche and his family were passengers on the world’s most famous ship, and their story did not end in the icy depths of the North Atlantic Ocean that fateful night in 1912. Their time in the spotlight is long overdue.

Have you subscribed to theGrio’s new podcast “Dear Culture”? Download our newest episodes now!

https://open.spotify.com/episode/2y0HsT5nqfpWKLxY51e1Rz

https://open.spotify.com/episode/7FCijwmrUx3SatVdGNcqhf

https://open.spotify.com/episode/1Qs5YBDGjckL3wHQgRqPtq