In her contentious interview with CBS News anchor Gayle King, Miya Ponsetto, 22, insisted that she, a Puerto Rican of mixed ethnicities, was not capable of being racist. The interview followed her attack on Keyon Harrold Jr., a 14-year-old Black boy she falsely accused of cellphone theft in a New York hotel lobby.

Read More: ‘SoHo Karen’ Miya Ponsetto charged, released from custody

This moment with Soho Karen, as she is now called by the internet, took me back to a time when I was about 12 years old — the time I learned blood is not always thicker than race.

It was a typical family squabble, something minor but blown out of proportion due to miscommunication.

One family member who is Latino and non-Black (Puerto Rican specifically), called another one of my family members, who is Black, the N-word.

Apparently, it wasn’t in the typical way it’s used around many mixed communities, where groups casually sling phrases like “n**ga” back and forth.

“How did they know to use that word?” I thought, as my Black family member explained what happened. “Why did they have to use that word?”

Read More: Alycia Pascual-Peña on repping Afro-Latina heritage on ‘Saved by The Bell’ reboot

I was horrified knowing despite my family’s bond by marriage with me as the link, nothing would ever truly be the same.

Many acts of love, birthday parties, Christmas gifts and home-cooked meals provided by this slur-throwing family member now felt stained by racism. I was darker than my Latino cousins due to my African American heritage on my father’s side: Did they see me the same way?

As a multicultural family, we may have all been “minorities” in America, discriminated against and denied opportunities for varying reasons. But when the lines were drawn, it’s sad how easily anti-Black racism became the weapon of choice.

This ugly and uncomfortable truth comes to mind when watching Miya Ponsetto. By all accounts, Ponsetto was not only insufferable and disrespectful to King throughout the interview, she issued a denial common amongst unaware people of color:

Ponsetto: “I wasn’t racial profiling whatsoever. I’m Puerto Rican, I’m, like, a woman of color. I’m Italian, Greek, Puerto Rican.

King: “You keep saying you’re Puerto Rican. Does that mean you can’t be racist because you’re a woman of color?”

Ponsetto: “Exactly.”

King: “Well, I would disagree with that.”

Ponsetto believed her identity as a “woman of color” of Puerto Rican heritage protected her from criminalizing a Black boy — who also happens to be Puerto Rican — in a hotel lobby altercation that could have gotten him killed.

Despite the popular “Butter pecan Puerto Rican” saying, being Puerto Rican is not a race. There are white Puerto Ricans with blue eyes and blonde hair, Black Puerto Ricans with 4c afros and chocolate brown skin, and every shade in between.

But let’s be clear — Ponsetto could’ve had a Black boyfriend, cousin, best friend or long-lost great-great-great grandmother and still be racist.

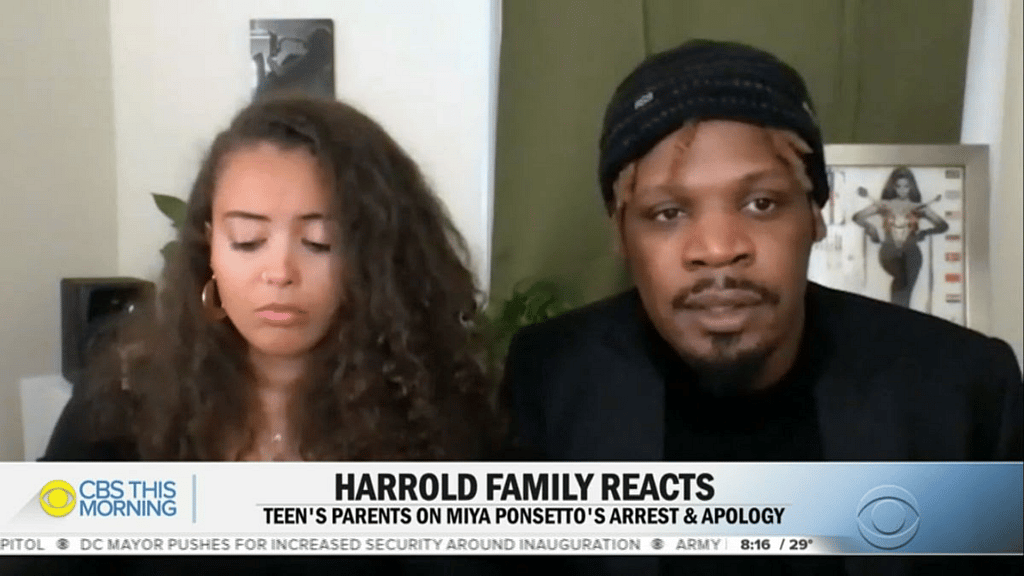

While Ponsetto was in Daddy-hat denial, her victim’s mother, Kat Rodríguez, who is also Puerto Rican, shared a strikingly different message while standing next to the Rev. Al Sharpton at a National Action Network press conference:

“This woman is a symbol of the privilege that is destroying our country,” Rodríguez said about Ponsetto.

“This woman is not only a racist but a menace to society … as usual it’s white privilege in America.”

These are two women of color, arguably bound by ties to the same community with drastically different understandings of systemic racism.

Theirs is a good example of why terms like “people of color” do not automatically translate into allyship or political wins for Black Americans. But also how when people of color are allies, they can call out anti-Black racism and create accountability.

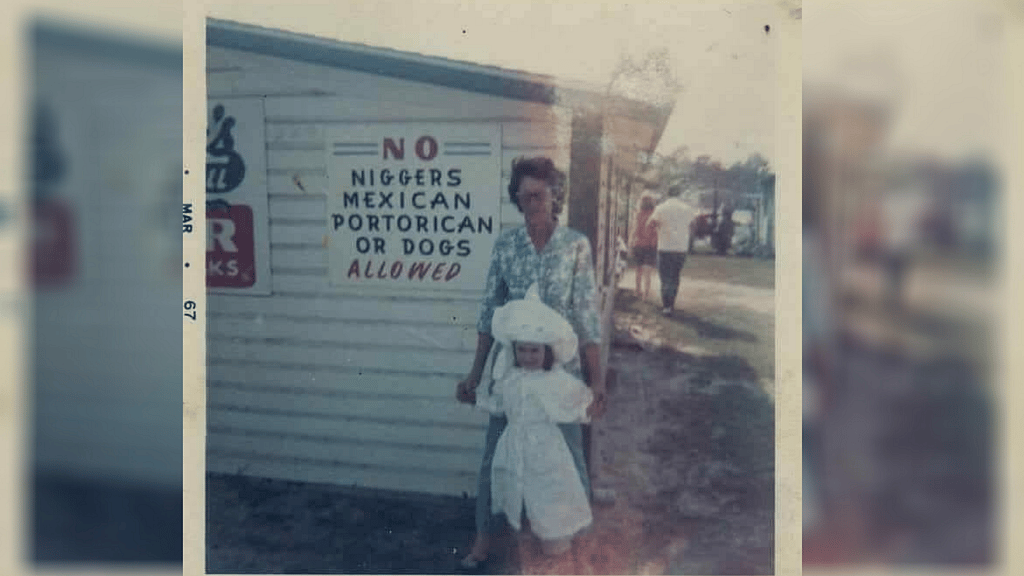

This country was built off a uniquely cruel and debased form of slavery that denied the humanity of enslaved African peoples and their descendants.

Read More: Biden, during Kenosha visit, says America will tackle ‘original sin’ of slavery

The American dream of flourishing together, while admirable, has always been undercut by racial hierarchies. Both racial and ethnic groups are positioned to be at war with one another, fighting for a place at the top in the land of the free, but always, always beneath whiteness.

African Americans are placed at the bottom, unfairly stereotyped and denied opportunities to the point where even some Black immigrants are inspired to distance themselves as well.

Even within the African American community, colorism persists, further segmenting us, because society celebrates and tangibly rewards distance from our own Blackness, down to the shade of our melanin and color of our eyes.

The flip side, “color-blind” societies where racism is completely denied and people are told they are “the same” but treated differently through environmental racism, economic oppression, and inequitable policing is also dangerous. (This is a big problem in Latin America and the Carribean, a dynamic explored in our new Grio documentary “Afro-Latinx Revolution: Puerto Rico,” released on Amazon this week. In it we explore how the island may see itself as a racial utopia, but many Black residents experience it as otherwise).

Read More: Afro-Puerto Rican identity explored in ‘Afro-Latinx Revolution: Puerto Rico’ documentary

It’s why “people of color” like Enrique Tarrio, who is Cuban, can be proud leaders of the Proud Boys and burn Black Lives Matter flags.

It’s why during celebrations of Black Americans, inevitably a “what-about-us” comparison emerges from a “person of color” celebrity, who can’t give Black folks 24 hours to be great.

Race is in fact a social construct. But our lived realities within the “containers created for us,” as Isabel Wilkerson describes in her best-selling book “Caste,” are very real.

Until people realize the struggles of Black Americans for equality and justice actually make way for the advancement of all, people will be uncomfortable with conversations that center Blackness — such as supporting Black-owned business, media and tech platforms, HBCUs, Black candidates and Black voter initiatives.

They will continue to flinch at elevating the notion that Black Lives Matter without a caveat (“don’t all lives matter though?”), or they can’t entertain that we deserve dedicated policies like reparations, affirmative action and voter protections.

Many people of color have similar struggles, despite our unique histories. There is power in unity. We saw that during the summer of 2020’s George Floyd protests.

While the different words we use to organize and mobilize may shift over time, from “negro” to “colored” to “Black” or “minority” to “people of color” and now, even the latest debated iteration “BIPOC” (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color), what hasn’t changed is the need to be seen.

It is also OK to address the issues of Black people, specifically and unapologetically.

Keyon Harrold Jr.’s mother understood this. Miya Ponsetto still does not.

Our country’s progress will rely on people of color who are willing to not just see us — but to fight against anything that threatens our lives and safety.

Even if that means starting right at home.

Natasha S. Alford is the VP of Digital Content and Senior Correspondent at theGrio. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram at @natashasalford.

Have you subscribed to theGrio’s podcast “Dear Culture”? Download our newest episodes now!

TheGrio is now on Apple TV, Amazon Fire, and Roku. Download theGrio today!