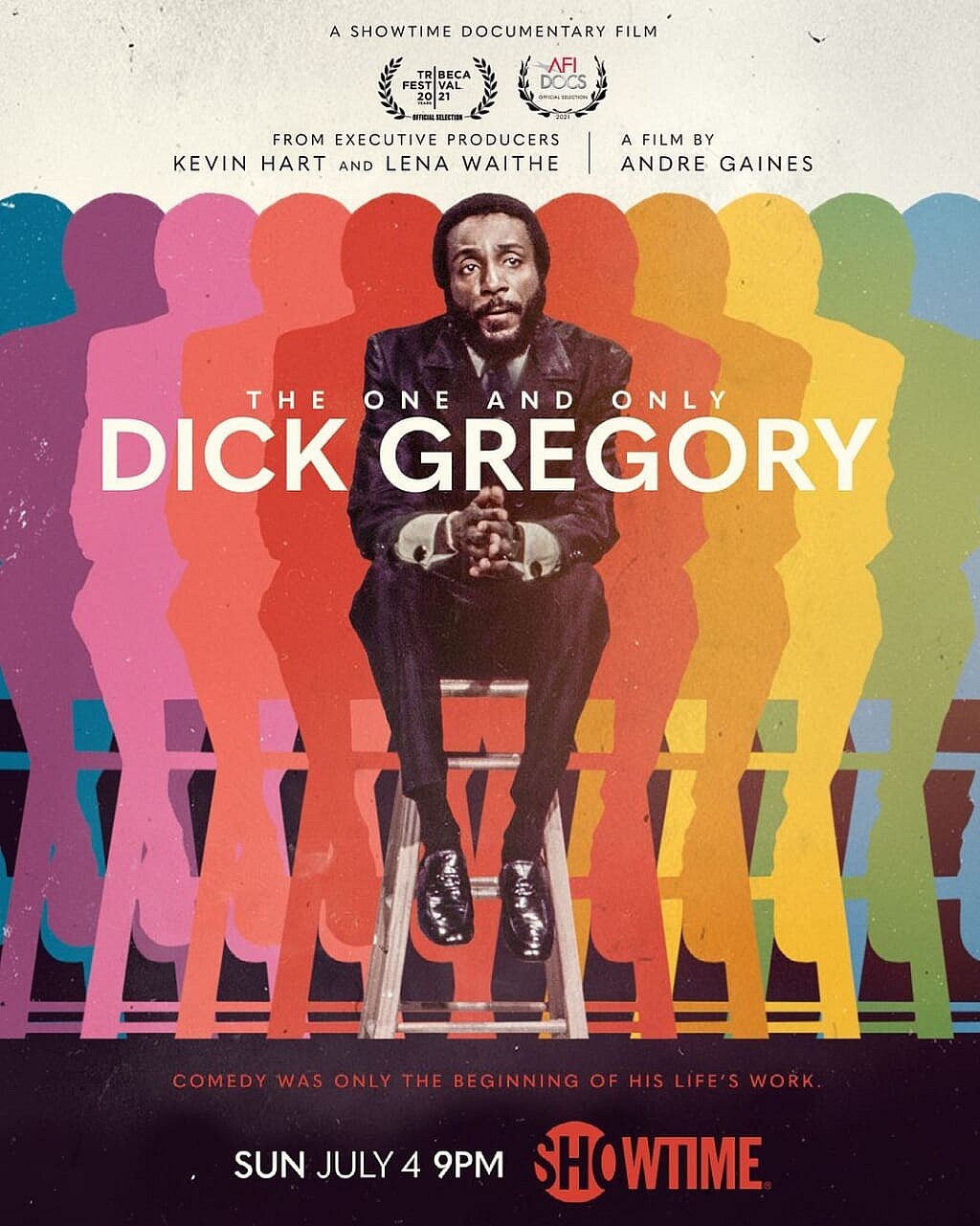

These days it’s rare to find a respected celebrity that doesn’t use their platform to speak out on issues like reproductive justice, transphobia, or racism. In fact, it’s practically expected of them. But back in comedian Dick Gregory’s day, amid Jim Crow America, there were strict lines drawn between performers and politics that, if crossed, could jeopardize their lives and/or career. But Gregory, as fondly detailed in writer-director Andre Gaines’ The One and Only Dick Gregory, couldn’t care less.

“I really do believe he had missions to accomplish, and it wasn’t just making jokes,” says biographer Robert Lipsyte in the documentary, recalling his many visits with Gregory throughout his career. Gaines opens the film with an animation illustrating a dismayed yet sharp funnyman in bed flitting from one diatribe to the next on everything from voter suppression and world famine to the Vietnam War.

It’s an intriguing way to introduce a figure who was practically consumed by the many problems that surrounded him and other Black and brown folks like him. It became unsurprising to hear him slyly joke, cigarette dangling between his fingers, about the Ku Klux Klan and other racist white people and throw a cold, blank stare into the crowd to see their reaction. “Back in my hometown, you had what was called a friendly Ku Klux Klan,” he’d begin. “Oh yeah, they’d come to your house and burn a cross. If they didn’t have no matches, they’d knock on your door and ask you for some.”

But there was clearly anger behind it, visceral frustrations he found a way to unpack on stage in a manner that didn’t totally make his white audience feel uncomfortable (at least initially). While doing so, he was engaging with his Black audiences who felt heard by a public figure who enjoyed tremendous success and yet, was sick and tired of being sick and tired just like them.

Executive producers Lena Waithe and Kevin Hart are two of Gregory’s contemporaries who were interviewed. They recalled watching Gregory, often in the same black and white footage repurposed in the film, and observed how he used his politics as a pathway to comedy, and not the other way around. Meaning, it was clearly his politics that motivated him; comedy was just the avenue through which he could express his views.

Weaving archival footage from Gregory’s comedy sets throughout the film, Gaines also shows clips of Gregory getting beaten by cops, marching in myriad protests, and collaborating with people like Martin Luther King, Jr. and Medgar Evers.

He was among the first Black comedians to infuse his identities as a performer and advocate, not unlike Nina Simone and Billie Holiday (though both go woefully unmentioned in The One and Only Dick Gregory) or actor Harry Belafonte who recalls his relationship with Gregory in the film. Gregory paved the way for people like Wanda Sykes, W. Kamau Bell, Dave Chappelle and Chris Rock who are all featured in the documentary.

But like his peers and predecessors, he paid a steep price for it, with the FBI even opening up an investigation into him. While The One and Only is a fairly straightforward biopic in that it chronicles its subject’s life from his upbringing in 1930s St. Louis, Missouri through his political/professional journey and ultimately to his final days, it mostly serves as a portrait of an artist pulled in many different directions. On one hand, he was the name on the tip of everyone’s tongues in the comedy circuit. On the other, he was the father and husband to Lillian, interviewed in the film along with a few of their kids (they had 10 total) who affectionately remember their dad, an avid runner, teaching them how to race down the street.

Still, there was the human rights side of Gregory that preoccupied him the most, so much that he later found his work as a comedian contentious. White journalists, unsurprisingly, would exhaustingly ask him whether he was trying to make the audience laugh or make a definitive point, as if a Black man in Jim Crow America, no matter how successful or famous, could possibly choose. But he would gracefully respond, “I happen to be a firm believer that you can laugh social problems out of existence. And the day we find a cure for cancer will be through jokes, will be through hard, sincere work.”

So, The One and Only Dick Gregory spends much of its latter runtime examining Gregory’s decision to leave comedy behind to devote his efforts to human rights through a bevy of biographic details. That includes fasting for nearly two years in the 1960s to protest the war, running from New York to Los Angeles in the 1970s to bring awareness to world hunger, and creating the “Bahamian Diet” to combat obesity particularly in Black and poor communities in the 1980s.

Though utterly astonishing, these bullet points in Gregory’s life never seem bombastic in the film, though you often might wonder how—even a man that essentially quit his day job—found time to be with his family. This question is never asked in the film. Presumably, his children’s glowing memories of him could have been used to, in part, address that. But the film doesn’t avoid the fact that he was compelled to make a comedy comeback very late in life in order to pay his bills, especially after his family’s home was repossessed.

Hollywood has already been trying to green light several other Dick Gregory films, particularly after his death in 2017, because his life story is so multifaceted, influential and complex. He is arguably one of the most profound, fascinating talents of any race, gender or era. But like its subject, The One and Only Dick Gregory makes an indelible mark in both history and entertainment.

Have you subscribed to theGrio’s podcast “Dear Culture”? Download our newest episodes now!

TheGrio is now on Apple TV, Amazon Fire, and Roku. Download theGrio today!