Okay, this is embarrassing. But when my son, who’s a freshman at Columbia, told me a few weeks ago that he was planning to see rapper Travis Scott at the Rolling Loud festival in New York City, I was initially more worried about whether the concert would distract him from his studies than I was about his safety.

We were still in a pandemic, and the event was going to be held in Citi Field late at night. But as a former music critic who had gone to more than his share of music festivals, I was okay with all of it. So my fully-vaccinated son masked up with his girlfriend and went.

My son and his girlfriend texted me right after the concert about what a great time they had. But only about a week later, Scott’s appearance at his Astroworld Festival in Houston ended with a tragic stampede — and the death toll is now up to 10. My heart breaks for the victims — and they have my condolences.

There were no reported serious problems during Scott’s Rolling Loud festival appearance in New York, but I began to wonder how safe my son and his girlfriend had really been that night. Was I wrong to bother my son with security concerns? Had I become a no-fun helicopter parent? Or are there real dangers associated with festivals I should be more concerned about?

In 1969, at the Altamont Speedway Free Festival featuring the Rolling Stones in northern California, an 18-year-old concertgoer was stabbed to death by a member of the Hells Angels motorcycle gang that the Stones had hired as security. In 1990, nine people were killed at the Roskilde Festival in Denmark when fans rushed the stage during Pearl Jam’s set.

In 2010, at the Love Parade electronic dance music festival in Duisburg, Germany, 21 people died after perhaps more than a million people tried to squeeze through a venue designed for far fewer. There were no reported deaths at the 2017 Fyre Festival on the Bahamian island of Great Exuma, but the event inspired documentaries on Hulu and Netflix alleging shabby lodging, substandard food, and shamefully-poor planning.

Sheets of rain transformed Woodstock ‘94, the 25th anniversary of the festival, into what people began calling “Mudstock II.” I was there for that one, covering it for Time magazine. Because of a shortage of showers, lodging and laundry facilities, many attendees began coating their bodies and faces in mud and embracing the disaster. The event was such a disaster it became memorable — and enjoyable in a weird way. Before the weekend was over, concertgoers proudly wore T-shirts reading, “I Survived Woodstock ‘94.”

Festivals have a special place in Black culture. Radio doesn’t always play our music, and concert promoters haven’t always pushed our artists. Festivals give us a chance to come together and celebrate our musicians. The recent documentary Summer of Soul detailed how the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival, which featured acts like Stevie Wonder, Nina Simone, and Sly and the Family Stone, helped fuse Black music with Black power.

The Smokin’ Grooves tour, launched in 1996 and revived in 2002, brought live hip-hop and neo-soul to mainstream audiences, with acts like The Fugees, A Tribe Called Quest and Erykah Badu. The annual Essence Music Festival, started in 1995, has become a showcase for soul music, gospel and exploring issues that concern Black women.

The Astroworld Festival, before the tragedy, was expected to give a cultural and economic boost to Scott’s hometown of Houston. According to the online lodging company Airbnb, the 2019 edition of the festival brought in almost $9.3 million in home shares booked through its app.

After the tragedy, critics have held up Astroworld as a symbol of the worst excess of hip-hop culture. Scott’s video apology for the tragedy, in which he speaks in a pained voice and rubs his forehead, has become a meme on TikTok.

After the Astroworld disaster, my son told me he reaccessed his experiences at Scott’s New York appearance. During the show, mosh pits full of thrashing dancers kept opening up around him and his girlfriend. Mosh pits are a thing at punk rock shows, but at hip-hop performances people don’t always know how to react.

My son moved to the back of the show to make sure his girlfriend stayed safe, and left a little early, as Scott was rapping his hit song “Goosebumps.” My son and his girlfriend had a good time, but looking back, they had to admit the whole concert had given them goosebumps. In any case, it was an experience they weren’t likely to forget.

Let me be clear — no entertainment is worth a body count. But from Woodstock to Rolling Loud, festivals give concertgoers a place to meet and dance and share experiences and maybe push the culture in new directions. Festivals are about live music and human interaction, two things that were in short supply at the height of the pandemic.

I always hate it when I see a group of teens — or adults — sitting around thumbing their phones and not talking to the people right next to them. Especially after two years of social distancing, it’s great to see people back out face-to-face at festivals, even if they’re all (as they should) wearing masks.

I want my son to stay safe, and part of me wants him to stay in his dorm room studying and listening to music on his headphones. But I know that nothing on Apple Music or Spotify can substitute for being at an outdoor festival, the beat booming through your bones, your favorite musician on stage, and kids your own age all around you. I still remember going to Smokin’ Grooves and other great festivals from decades ago and seeing all the great Black musicians I wasn’t seeing on late-night TV.

Everyone should work to make festivals safer. But we’ve got to keep making more festivals.

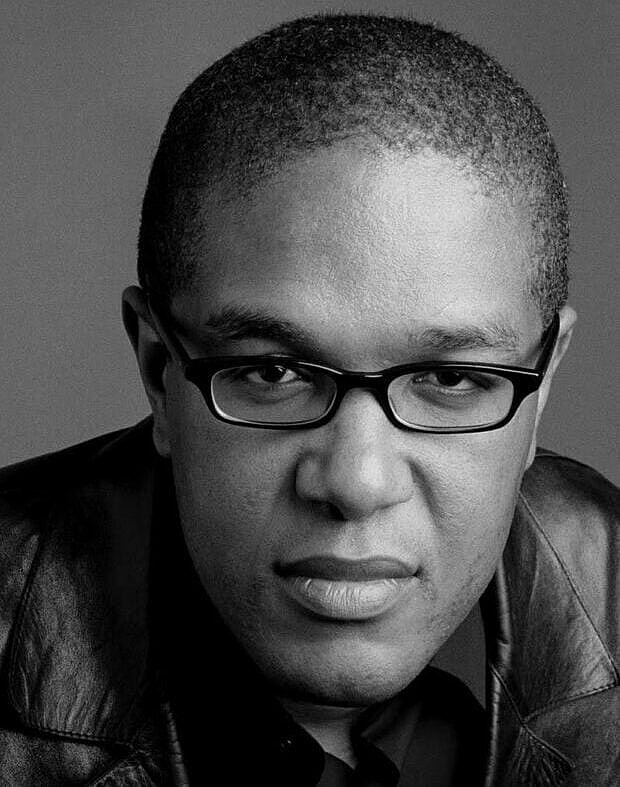

C.J. Farley is a former music critic for Time magazine and the author of the young adult book “Zero O’Clock.”

Have you subscribed to the Grio podcasts, ‘Dear Culture’ or Acting Up? Download our newest episodes now!

TheGrio is now on Apple TV, Amazon Fire, and Roku. Download theGrio today!