I, too, sing America: celebrating the poetry of the Black lyricist

As National Poetry Month comes to an end, theGrio acknowledges the importance and impact of lyricism in Black music

Langston Hughes is regarded as one of the greatest poets to ever walk a turn in this country. It’s for good reason, too. Hughes had an unparalleled knack for presenting existential quandaries and telling elaborate, three-dimensional stories.

Like poetry, music acts as a mirror of society. It equally shows all of its blemishes and imperfections, as well as its beauty and simplistic charm. This is why when celebrating poetry, the Black lyricist deserves to be included in the rhetoric. The thread and connection of the poet to the lyricist is evident throughout American history.

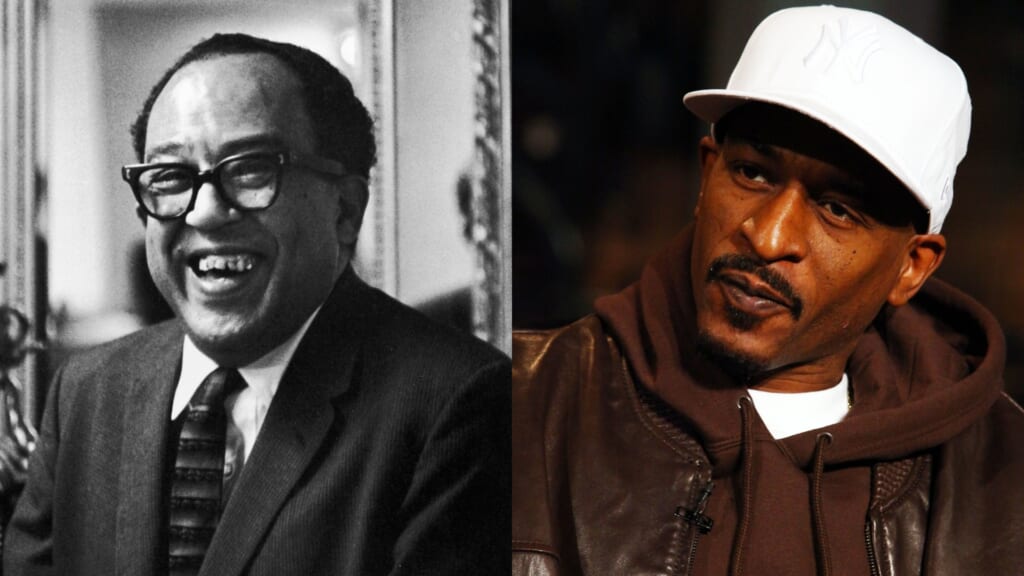

In Hughes’ piece “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” he writes, “I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins.” Here, he gives the reader a tome’s worth of information about his origins and how his surroundings have molded him. Wu-Tang Clan rapper Raekwon the Chef displayed the same ability in the song “C.R.E.A.M.:”

“I grew up on the crime side,

The New York Times side,

Staying alive was no jive

Had secondhands,

Mom’s bounced on old man,

So then we moved to Shaolin land.”

In a short passage, Raekwon was able to explain the dangers of his native Staten Island, the existence of poverty, and the absence of his father.

Sure, Raekwon has the benefit of having his words accompanied and enhanced by music, but that makes it no less potent and impressive. To be profound through simplicity is incredibly difficult. Both great poets and great lyricists have that power.

On Hughes’ “Mother to Son,” he wrote: “Don’t you fall now – For I’se still goin’ honey; I’se still climbin’, and life for me ain’t never been no crystal stair,” a celebration of a Black mother’s influence on her man-child through the unfathomable obstacles of her own existence.

The same heartache and hope can also be heard in the pen of Tupac Shakur in “Dear Mama.”

“And even as a crack fiend, mama,

You always was a Black Queen, mama,

I finally understand,

For a woman, it ain’t easy trying to raise a man.”

In some quarters, lyricists and musicians aren’t viewed in as high regard as many of our legendary poets. Hughes, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Maya Angelou, Nikki Giovanni, and so many others were also activists who served their communities.

But musicians and lyricists (many of whom are both) have penned lyrics that are just as moving as poems. r

On “I Know You Got Soul,” Rakim wrote about the metaphysical process of writing an intricate rap:

“I start to think and then I sink,

Into the paper like I was ink,

When I’m writing, I’m trapped in between the lines,

I escape when I finish the rhyme.”

Few lyricists can capture the concept of love like Stevie Wonder. In “As,” he writes of a love so deep, it will transcend the lives of him and his lover:

“As today I know I’m living,

But tomorrow could make me the past,

For that I mustn’t fear,

For I know deep in my mind,

The love of me I’ve left behind.”

Alas, when love goes wrong, poets and lyrics are both even more expressive. Smokey Robinson, once called the greatest American poet by Bob Dylan, had many such passages that address heartbreak:

“The way you wrecked my life,

Was like sabotage,

The love I saw in you was just a mirage.”

Frank Ocean expressed similar feelings in “Bad Religion,” writing about loving someone who didn’t return his feelings.

“If it brings me to my knees, it’s a bad religion,

This unrequited love

To me, it’s nothin’ but a one-man cult.”

Black poets and musicians have always been able to diagnose the nation’s social ills. Just think of Giovanni’s “The Funeral of Martin Luther King, Jr.,” as an example as she wrote,

“His headstone said

FREE AT LAST, FREE AT LAST,

But death is a slave’s freedom,

We seek the freedom of free men.”

In “Concrete Jungle” Bob Marley expressed the same struggle of being bound by oppression, yet putting on a brave face despite it.

“No chains around my feet,

But I’m not free,

I know I am bound here,

In captivity,

Never know what happiness is,

Never know what sweet caress is,

Still, I be always laughing like a clown.”

Years later, Lauryn Hill, the mother of five of Marley’s grandchildren, mused in “Mystery of Iniquity” about how the pursuit of capitalistic goals and ambitions preached by American gatekeepers leads to madness and the cyclical destruction of free thought and individualism:

“The revolving door, insanity every floor,

Skyscraping, paper chasing,

What are we working for?

Empty traditions, reaching social positions,

Teaching ambition to support the family superstition?”

In the face of all that Black Americans have to overcome, there is always hope — escapism is found while we still breathe. This concept is illustrated eloquently by Billy Strayhorn in “Lush Life.”

“I live my day as if it was the last

Live my day as if there was no past”

So, the next time you hear a beautiful, poignant, or heartbreaking song, take some time to appreciate the amazing poetry from Black poets and lyricists, from Curtis Mayfield and Bill Withers to Andre 3000 and Jill Scott. As Dunbar once wrote, they “know why the caged bird sings.”

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku and Android TV. Also, please download theGrio mobile apps today!