What will the lingering effects of gun violence in schools do to future generations?

OPINION: Gun violence begets poor mental health, therefore we cannot talk about one without addressing the other. And we cannot wait for bickering politicians to agree on how to do the right thing.

Editor’s note: The following article is an op-ed, and the views expressed are the author’s own. Read more opinions on theGrio.

Gun violence in schools is breaking young people before they’ve had a chance to come into their own.

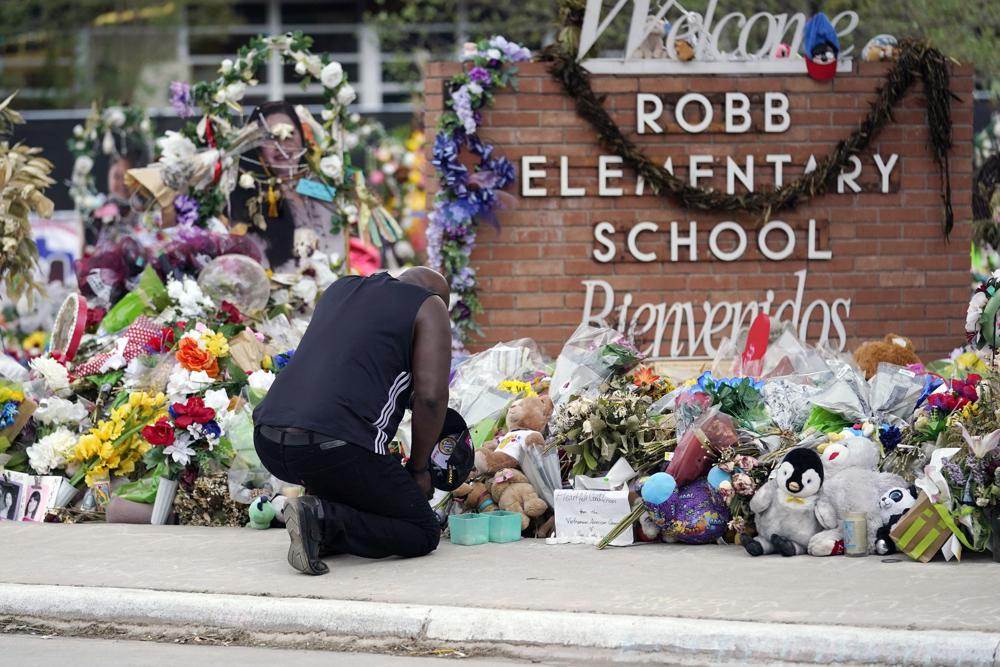

Many of us simply cannot relate to the pain, anguish and terror that anyone involved in a school shooting experiences, but a new report on the Uvalde, Texas, school shooting (and its botched response by law enforcement) is a stark reminder that the mental health of our future generations is in jeopardy.

No country in the world has had more mass school shootings (really mass shootings period) than the United States. Since 1970 there have been over 2,000 school shootings, with nearly half occurring in the past decade—since the country’s deadliest tragedy at Sandy Hook Elementary School took place in December 2012; and since 1999—the year of the Columbine High School attack that resulted in the murder of 12 children and one teacher—311,000 students have been on campus during a school shooting.

As a result, we have a generation of young people who feel unsafe in “safe” spaces. Seemingly peaceful situations feel less so, and the internal violence barometer that gauges whether a situation feels insignificant or alarming seems to be perpetually skewed towards the latter. This hyperacuity manifests itself in physical and psychological ways. Anxiety presents in a constellation of symptoms like feeling more tired than normal and having trouble concentrating. Others may feel like their heart is racing or the need to constantly look over their shoulder. Anxiety coupled with the real threat of violence strains relationships with classmates, teachers, school security, and police officers.

Students and staff that witness school shootings are more likely to develop acute stress reactions in the days and weeks after the event, as well as chronic psychiatric disorders like generalized anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), all of which require treatment centered on professional medical care and constant love and support from friends and family members. Witnessing or hearing about a school shooting can lead to debilitating nightmares, flashbacks and avoidance of situations that serve as reminders of the traumatic event—common symptoms of PTSD. Depression, a common sequelae and concurrent psychiatric disorder that accompanies PTSD may also ensue. In fact, over three-fourths of people with PTSD also experience depression.

School shootings don’t just have negative ramifications for those involved; they also impact those of us who witness the atrocities on television and social media. A 2019 survey by the American Psychological Association (APA) found that nearly 80 percent of responders said they were stressed about possible mass shootings, and one-third expressed a reluctance to partake in once enjoyable experiences, with rates highest among Black and Brown people.

Many young people do not have access to the familial support structures that can offset the negative effects of childhood trauma; or the tools needed to navigate our fragmented and confusing healthcare system in search of insurance, mental health providers, and support group networks…nor should they have to.

Sadly, mental health concerns are swept under the rug because the issues of gun law reform and school protection often take precedence in the public eye. Most Americans agree that schools are sacred spaces where our youth should be able to flourish in an environment free of bullying, gun violence, or harassment, but schools are progressively becoming less safe, serving instead as defenseless targets that perpetrators can prey on. Schools are gun-free zones that don’t shoot back, therefore they are prime targets for attacks by cowards looking to exploit their vulnerabilities.

Despite enduring tragedy after tragedy, the idea of protecting schools with armed professionals has been met with resistance. The idea of guns in schools seems to make some parents uncomfortable because the proposition seems antithetical to the traditional belief of school as a safe space. Unfortunately, the days of schools being “off-limits” to real violence—not counting playground school fights that result in more chanting than actual fisticuffs—are long gone.

At some point, we must ask ourselves if leaving schools ill-equipped to defend themselves is a practice of willful ignorance. Stricter gun laws and taking more aggressive action at the hint of any threat to school safety would likely lower gun violence rates, but when the problem has gotten this far out of control it begs the question if schools should be equipped with the same armored protections as courthouses, police stations, military bases, and nuclear facilities. If our president, representatives, diplomats, and visiting dignitaries are protected, to some degree, by guns—shouldn’t our children be as well?

I am a pacifist—if I could live in a world without guns I would be all for it—but I am also a realist, and a doctor, who has seen far too many lives impacted by gun violence. Gun lobbyists have placed their stake in the ground, and without an assault rifle ban or stricter requirements to acquire a gun, the issue of gun violence in schools is likely to get worse.

I can’t unsee the mental and physical toll on our collective health as a result of gun violence, so any way to decrease the imminent threat of school violence and therefore increase confidence in school safety must be on the table. The “system” we have in place simply does not and has not worked for a very long time. Therefore, primary and secondary prevention strategies to lessen the frequency of school shootings and help those who have already experienced them must be addressed at the same time.

Still, more guns—even in the hands of good, mentally sound adults—do not protect the mental and emotional health of our young people. Society carries the collective weight of gun and mental health reform. Gun violence begets poor mental health, therefore we cannot talk about one without addressing the other. The solutions start with gun reform and electing officials who will actually enact change, but we cannot wait for bickering politicians to agree on how to do the right thing.

Teachers, principals, superintendents, and staff must learn about the warning signs of gun violence, so they can know the steps to take to prevent the Uvaldes’ and Sandy Hooks and Columbines from happening. Teachers and support staff must also accept their re-imagined job descriptions as front-line protectors of our young people from physical violence. School districts should be held accountable for providing adequate preventative mental health resources before and after gun violence drills such as “hide under your desk drills” and hire mental health-care professionals to discuss the importance of safeguarding your mental health when mass shootings are not happening (like taking breaks from the daily news cycle).

At St. Francis College, I teach an ethics and decision-making class that unpacks elements of social discord like conflict resolution, working in uncomfortable situations, bullying, cancel-culture and how to find common ground with those whom we respectfully disagree with. Classes like these build resilience and should be standard across all middle and high schools.

Life is hard enough on its own, but today’s generation has to contend with school violence on top of cyberbullying, a raging opioid epidemic, a school schedule repeatedly interrupted by a global pandemic, and more social demands than ever. Making it our individual and collective responsibility to protect their mental health is the least we can do.

Dr. Shamard Charles is the executive director of graduate studies in public health at St. Francis College and sits on the Medical Advisory Board of Verywell Health (Dot Dash-Meredith). He is also host of the health podcast, Heart Over Hype. He received his medical degree from the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University and his Masters of Public Health from Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Previously, he spent three years as senior health journalist for NBC News and served as a Global Press Fellow for the United Nations Foundation. You can follow him on Instagram @askdrcharles or Twitter @DrCharles_NBC.

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku, and Android TV. Please download theGrio mobile apps today!