What the yearlong Russia-Ukraine war means for Africa

From food shortages to higher costs for energy and goods, African countries are paying a heavy price for Vladimir Putin’s unprovoked war.

As the world marks one year of Russia’s deadly and costly war in Ukraine, Americans and allied nations continue to stand in solidarity with Ukrainian citizens in their fight to preserve their sovereignty.

President Joe Biden’s trip to Ukraine this week — and the announcement of an additional half a billion dollars in military aid — is emblematic of how committed the United States remains to protecting Ukraine’s democracy. That commitment has also been backed by clear support from NATO allies.

But consequentially, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine also has had ripple effects on the African continent. From food shortages to higher costs for energy and goods, African countries are paying a heavy price for Vladimir Putin’s unprovoked war.

How has Russia’s war in Ukraine negatively impacted African nations?

Russia imposed a blockade of Ukraine’s ports in the Black Sea upon its invasion in February 2022, resulting in the disruption of exports such as wheat, oil and fertilizers. Consequently, many African nations, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, experienced critical food insecurity. As another consequence, sanctions on Russia by the United States and European Union led to trade issues and made it more expensive for African countries to import goods from Russia.

The immediate consequences of Russia’s war in Ukraine around the globe — but especially in Africa — were a “wake-up call,” says Mvemba Phezo Dizolele, a senior fellow on Africa at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

“How can a continent that is home to a large percentage of arable lands — a continent that can feed the world literally — be dependent on two countries that are so far away?” Dizolele queried.

The Africa scholar noted that it results from “years of mismanagement” and “not really following through to various visions of self-sufficiency across the continent.”

“The countries have tried to adopt new ways of doing agriculture or feeding themselves,” Dizolele told theGrio. “But it has not been as revolutionary as they ought to be, considering all the ingredients and all the resources that Africa has to feed herself.”

As one of the world’s top exporters of crops, Ukraine is known as the breadbasket of the world.

African policy expert Dorothy Davis told theGrio that the status resulted in Africa and nations worldwide being “held hostage” because Ukraine was “under attack by Russia.”

“Maybe that will get leaders to fast-track the process of growing their own and therefore creating jobs within their own countries and creating more sustainability,” said Davis, who runs the advisory firm Dorothy M. Davis Consulting.

As Ukraine continues to successfully fight back against Russia and reclaim some territory, things have improved somewhat.

“It’s not as bad as it was,” said Joseph Tolton, an African policy expert who runs the pan-African advocacy group Interconnected Justice. “African countries are getting more supplies from other places.”

Still, Tolton told theGrio, other economic challenges persist, such as the high cost of fuel, which is also an issue globally.

“It’s really squeezing and crushing the middle class just because of the difference as it relates to disposable income and savings that Africans have,” he explained. “Truck deliveries have to pay for fuel, which increases their cost. Even transporting your kids around — basic transportation.”

Tolton noted that, unlike the United States and other Western countries, African nations “don’t have the same opportunities … in terms of mass transportation like trains.”

It’s also worth noting that when the Ukraine war first broke out, African migrants in Ukraine faced discrimination at the border while trying to flee for safety.

“I can’t say all of us were surprised because racism is everywhere. It’s endemic,” said Davis. “This issue of how Africans are treated in the whole Ukraine war scenario is considered part of all the other issues that we all experience as people of African descent across the globe.”

The irony of Africa’s close ties to Russia

What’s noteworthy — and a bit ironic — about Africa’s vulnerabilities to the Ukraine war in the past year is the continent’s ties to Russia. Several African countries have refused to condemn Russia publicly for its invasion of Ukraine, much to the dismay of the United States and its Western allies.

On Thursday, member states of the United Nations General Assembly voted 141-7 on a resolution that calls for peace and the immediate end of Russia’s war in Ukraine. However, 32 countries abstained, many of which were African. Similarly, at the beginning of last year’s war, 17 African nations remained neutral during a U.N. vote on a resolution to condemn Russia.

“In reality, no close observer of Africa was surprised by that. But in the West, it was a big kind of shockwave,” said Dizolele. “It became clear that African countries are countries with interests … Western countries are not the only friends that African countries have.”

The geopolitical background as it relates to Africa and the number of world powers that have investment and trade interests there is varied and complicated at best. One example is South Africa, which also abstained from condemning Russia over the Ukraine war.

Though South Africa and the United States share close ties as two democratic nations that promote progressive values — like racial equality and advancing LGBTQ+ rights — Tolton noted it was initially Russia, not the U.S., that sided with the African National Congress, South Africa’s political party against apartheid, in the 1980s.

“During the Reagan administration, the Soviet Union (what is now Russia) was actually on the side of the [ANC], both morally and in terms of supplying them with weapons and training,” he recalled.

“This,” Tolton continued, “was while the Reagan administration was not speaking out against apartheid and had no interest in doing so until African Americans via TransAfrica … really mobilized … to push the Reagan administration around its position around South Africa.”

Dizolele said the Ukraine war had fed a Western narrative suggesting Russia is manipulating African nations through misinformation and even that they should “watch out” for China. He said that narrative “comes with a risk” because it “presupposes that Africans do not have their own agency in deciding its principles,” and Africans “don’t know what they’re doing.”

The U.S. seeks to move Africa away from Russia through diplomacy

Emphasizing Africa’s agency has been a core part of the United States’ renewed outreach to improve relations with the 54 nations on the continent. In December, the Biden-Harris administration invited 49 African heads of state for the first U.S.-Africa Summit since the Obama administration hosted African leaders in 2014. However, the administration has downplayed the suggestion that its strategy with African nations has anything to do with Russia or China.

Instead, the U.S. has focused on committing billions of dollars to Africa for a range of investments and aid through input from the African Union regarding the support they would like to see.

“In the U.S.’s effort to win minds and hearts, so to speak, of Africans in the context of the U.S.’s competition with China and Russia, the U.S. has to focus more on development issues, as opposed to a chess game between China and Russia,” said Davis.

“President Biden is going down the right path,” she added, “but we’re talking probably centuries of this. It’s going to take some time to reverse.”

How is the U.S. helping Africa amid the Ukraine war?

While the war in Ukraine appears to be far from over, the United States has made moves to assist Africa in its challenges amid the conflict, including commitments for 2023 “to accelerate progress toward achieving food security, building stronger food systems and more diversified supply chains and expanding African countries’ access to agricultural markets.”

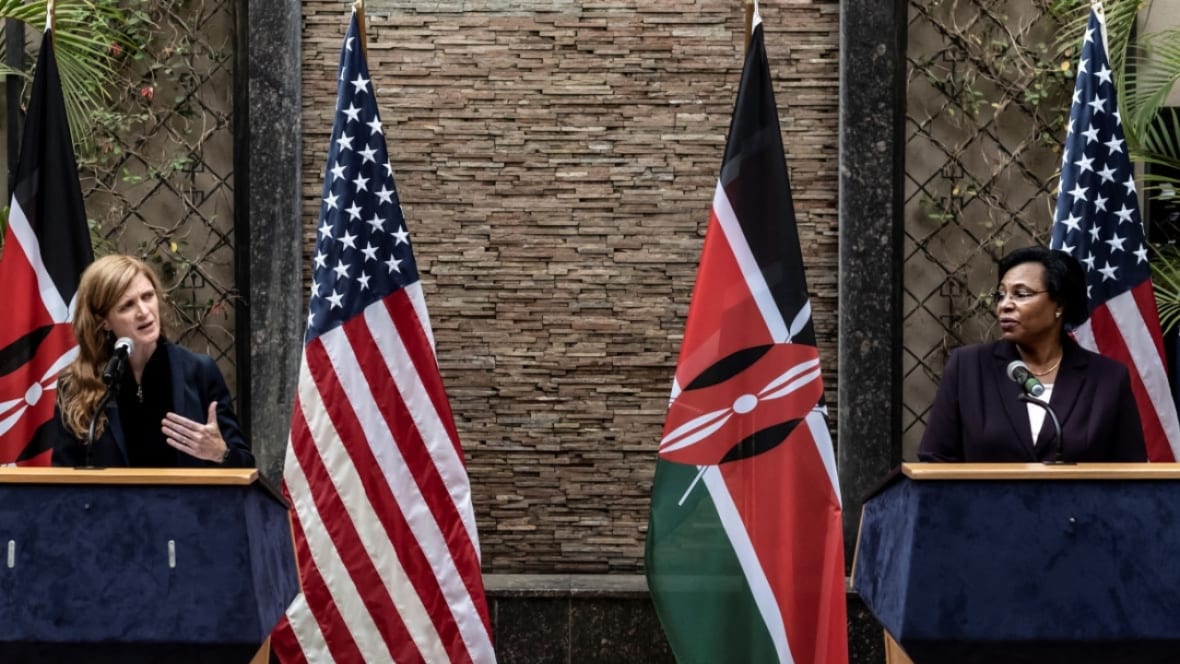

Dizolele applauded the United States’ Feed the Future program through the U.S. Agency for International Development for “putting a lot of money into engaging with African countries,” including a commitment of $5 billion over five years. He also noted that USAID Administrator Samantha Power pledged about $1.2 billion to “help stem the standing famine that was tightening the Horn of Africa.”

Tolton believes the United States has addressed the negative effects of the Ukraine war in Africa “fairly from an economic perspective.” Overall, he said, he would grade the administration a C+ on its spending in Africa in comparison to the tens of billions of dollars in military and humanitarian aid it provided to Ukraine to date.

“It’s been adequate, but certainly, it hasn’t been rich or abundant,” he shared. “The amount hasn’t been so big, but it’s been noticeable and impactful.”

Beyond addressing the issue of hunger, however, Tolton said there’s a “missed opportunity” for the Biden administration to “tie together why Ukraine matters for Africa beyond food insecurity.”

“We are talking about pushing back against one of the most violent autocrats in the world, who has clear intentions around reestablishing the Soviet Union as an empire,” said Tolton. “His example as an autocrat is a big problem for Africa.”

“That is not a continent-wide struggle, but it is a global struggle,” he contended, “and therefore, all that are for democracy and open markets and the advancement of human rights and civil society on the continent of Africa, by default, are on the side of Ukraine.”

“There’s a real opportunity to actually bring many African nations closer to us,” he continued, “if we were to lift up that not only as a message but also put some teeth behind it, in terms of how we’re really going to work to further the promotion of democracy globally, but also in the case of Africa.”

Gerren Keith Gaynor is the Managing Editor of Politics and White House Correspondent at theGrio. He is based in Washington, D.C.

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku and Android TV. Also, please download theGrio mobile apps today!