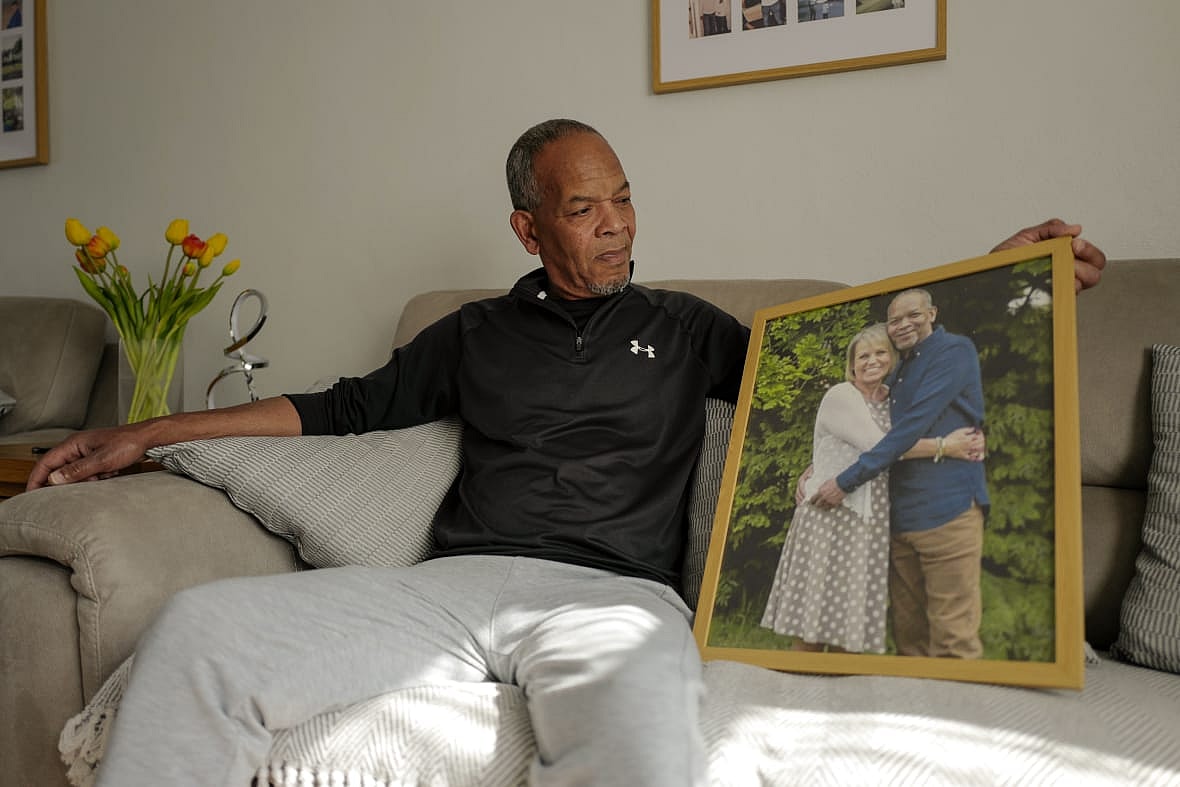

LONDON (AP) — When Thomas Tobierre’s wife, Caroline, died in 2021, he didn’t know how he was going to pay for her funeral.

That’s because he had drained his savings while caught up in a U.K. immigration crackdown that improperly targeted legal residents largely from the Caribbean and other parts of the former British Empire. While a government compensation program eventually covered the cost of his wife’s funeral, Tobierre is still fighting for reimbursement of the 14,000-pound pension ($17,891) he cashed in to make ends meet when no one would hire him because of his disputed right to work.

He isn’t alone. Five years after the U.K. government apologized and promised to compensate those who were affected in what became known as the Windrush scandal, thousands of people who had their lives upended are still battling for what they consider fair settlements.

“They’ve got no compassion,” Tobierre told The Associated Press, referring to the slow-moving compensation claims process. “They need to be aware that what they’re doing is utterly, grossly wrong.”

The comments underscore the frustration of many people of Caribbean descent who complain the government is dragging its feet even as it prepares to mark the 75th anniversary of Windrush Day, the symbolic start of the mass migration that reshaped the U.K. after World War II. Events scheduled around the country will celebrate the contributions Caribbean immigrants have made to Britain since June 22, 1948.

Almost 500,000 people from Britain’s Caribbean outposts came to the U.K. between 1948 and 1971, invited by the government to help rebuild a nation ravaged by the war. As citizens of the British Empire, they had the right to live and work in the country. Few documents were required, especially for children, who often traveled on their parents’ passports.

The Windrush scandal first came to light in 2018, when Britain’s news media began reporting on the stories of long-term residents who had lost their jobs, homes and benefits, such as free medical care, because they couldn’t produce paperwork proving their right to live in the U.K. Some were detained, and dozens were deported to countries they barely remembered.

While the government pledged that those wrongly targeted would be compensated swiftly, advocates for the victims say that promise has gone unfulfilled.

The most recent data from the Home Office, the government department that oversees immigration and the compensation program, shows that 46% of the 6,122 claims were “fully closed” as of April, indicating that all appeals had been exhausted. But the number of outstanding victims may be far higher. The Home Office had estimated there were about 12,000 victims — though not all have come forward to make claims.

Part of the reason for a discrepancy may be because many of the affected residents are uncomfortable presenting claims to the Home Office, which was responsible for the original crackdown.

Almaz Teffera, a racism researcher at Human Rights Watch, argues that administration of the program should be turned over to an independent body.

“How can a compensation scheme be held by the same agency that also committed the wrongs?’’ Teffera said. “There is a trust issue in the scheme from the very get-go.”

Home Secretary Suella Braverman acknowledged there was more to do, but she insisted that the agency had made progress.

“I and the whole of government remain absolutely committed to righting the wrongs of the Windrush scandal,” Braverman said in a statement. “Already we have paid or offered more than 72 million pounds ($91.7 million) in compensation to those affected, and we continue to make improvements so people receive the maximum award as quickly as possible. But we know there is more to do, and will work tirelessly to make sure such an injustice is never repeated.”

After early complaints about the program, an independent review completed in 2020 recommended widespread changes to speed up claims processing.

But two years later, a follow-up report found that the Home Office had failed to implement some of the most important recommendations, including improved training on issues of race, hiring more senior staff members from minority ethnic communities and increasing outside scrutiny of the agency.

Lawyers working with Windrush victims say that little has changed despite the Home Office’s commitment to honor the recommendations.

Nicola Burgess of the Greater Manchester Immigration Aid Unit said if that anything, things are worse.

“Many families were torn apart because of this,’’ Burgess said. “So it was always a political issue. Absolutely. And now five years on, I would say it is a political issue again, because they have rolled back on their commitment to right wrongs.”

Victims also complain about the complexity of the process, which involves filling out a 44-page questionnaire and providing documents to verify where a claimant came from, how long they’ve been in Britain and how they were affected.

Even those with legal help struggle to provide all the information required, and those without assistance are sometimes scared off, victim advocates said.

“Imagine having to put together an application form that requires you to go back 30 years … to substantiate that you have, in fact, incurred these losses,” Teffera said. “And so, it’s retraumatizing.”

The Home Office acknowledged in December 2021 that it had made a “slow start” in compensating people, but said it had overhauled the program to make it simpler and faster.

Thomas Tobierre isn’t convinced.

His story begins like that of many caught up in the Windrush scandal.

Born on the island of St. Lucia, Tobierre moved to Britain with his family in 1961 when he was 7. Like many young people at the time, he traveled on a family passport.

His troubles began in 2017, when the company he had worked at for almost three decades closed and he had to find a new job.

He soon discovered that rules designed to combat illegal immigration meant he had to show proof of his right to work before anyone would hire him. But without a British passport or immigration documents, he couldn’t satisfy employers, even though he had worked and paid taxes in the U.K. since he was 15.

He eventually secured the right documents, but it took a year. In the meantime, he maxed out his credit card and cashed in his pension.

His wife Caroline, a cleaner, took on more work to help make ends meet. When she told her family she was very tired, they put it down to the extra hours. It was only later, when she was diagnosed with Stage 4 bowel cancer, that they understood it was something more serious.

With a new job and no seniority, Thomas struggled to get time off to accompany her to chemotherapy appointments, particularly since he had to take public transportation after selling his car.

It was about this time that newspapers started reporting on the broader Windrush scandal and Tobierre discovered others had similar issues. After much tangling with the bureaucracy and when it became clear Caroline’s cancer had spread, Tobierre finally accepted an offer of compensation from the Home Office, because he knew she didn’t have much time left.

Caroline’s own claim for the impact on her as a family member wasn’t processed before she died despite pleas from the family that she had but weeks to live. Desperate to pay for her funeral, Thomas and the couple’s daughter Charlotte outlined their wish to give her a proper funeral on a national radio program.

Later that afternoon, the Home Office offered her a payment of 20,000 pounds, a sum ultimately increased to 40,000 pounds.

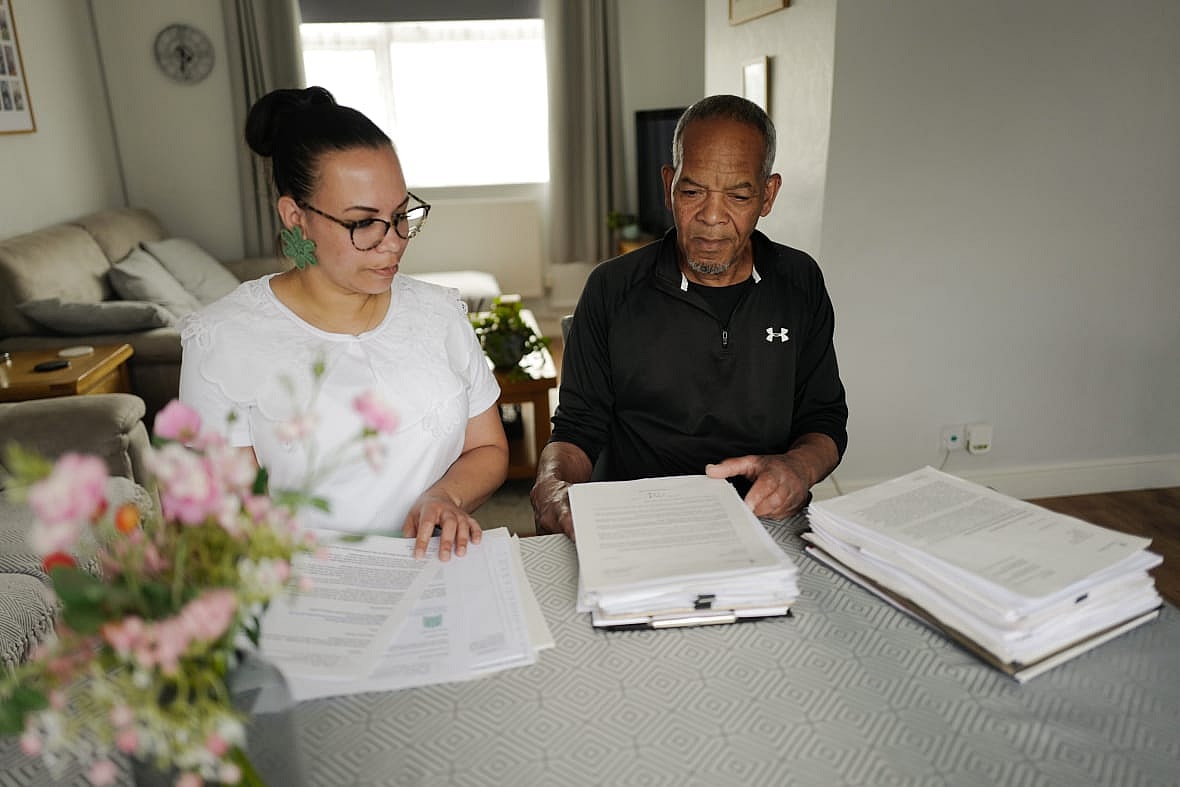

Charlotte continues to fight, protesting the Home Office’s failure to reimburse her father for his lost pension and filing her own as a family member.

Fighting for everything, documenting everything and dealing with an anonymous bureaucracy that moves at a glacial pace has been very hard, she said. But she and her father keep telling their story since many claimants have no one.

“It’s a big trauma,’’ Charlotte said of her dealings with the Home Office. “They can compensate moneywise, but it’s definitely a lifelong scar that I think every Windrush claimant will bear.’’

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku, and Android TV. Please download theGrio mobile apps today!