“Are you participating in Ramadan this year?”

This is the question my sister and I often ask each other, even when we already know the answer. It is a question I wish neither to answer nor be asked. It reminds me that I am only Muslim by word and by name.

Islam is my mother’s religion. In her search for something to believe in, she met my father, a ruthless man who just happened to hold the key to her salvation: Islam. My father came to Islam by way of cliché; in his attempt to escape the Vietnam War, he was eventually arrested and imprisoned for nearly two years. While in prison, my uncle, Ahmed, sent my father The Holy Qur’an. In Chicago, a city with a large Muslim population anchored by the Nation of Islam, my mother and father met, changed their names, and created a new family name for themselves and their children: Karim. It was their hope that we would be a generation of Muslims who surpassed the grief of their past lives.

Islam seemed to be a utopia, with its promise of peace and salvation through the regimen of faith, prayer, fasting, modesty, and community. I wanted to be a part of that utopia. I wanted to be part of something greater than myself. I wanted to be accepted and welcomed by the community.

However, a religion formed by a prophet (peace be upon him), continued through a master, and later congealed by a minister didn’t quite serve the curiosity that lay within me. I held far too many questions that never seemed to have an answer, which led me astray.

To date, I have been “astray” for 25 years.

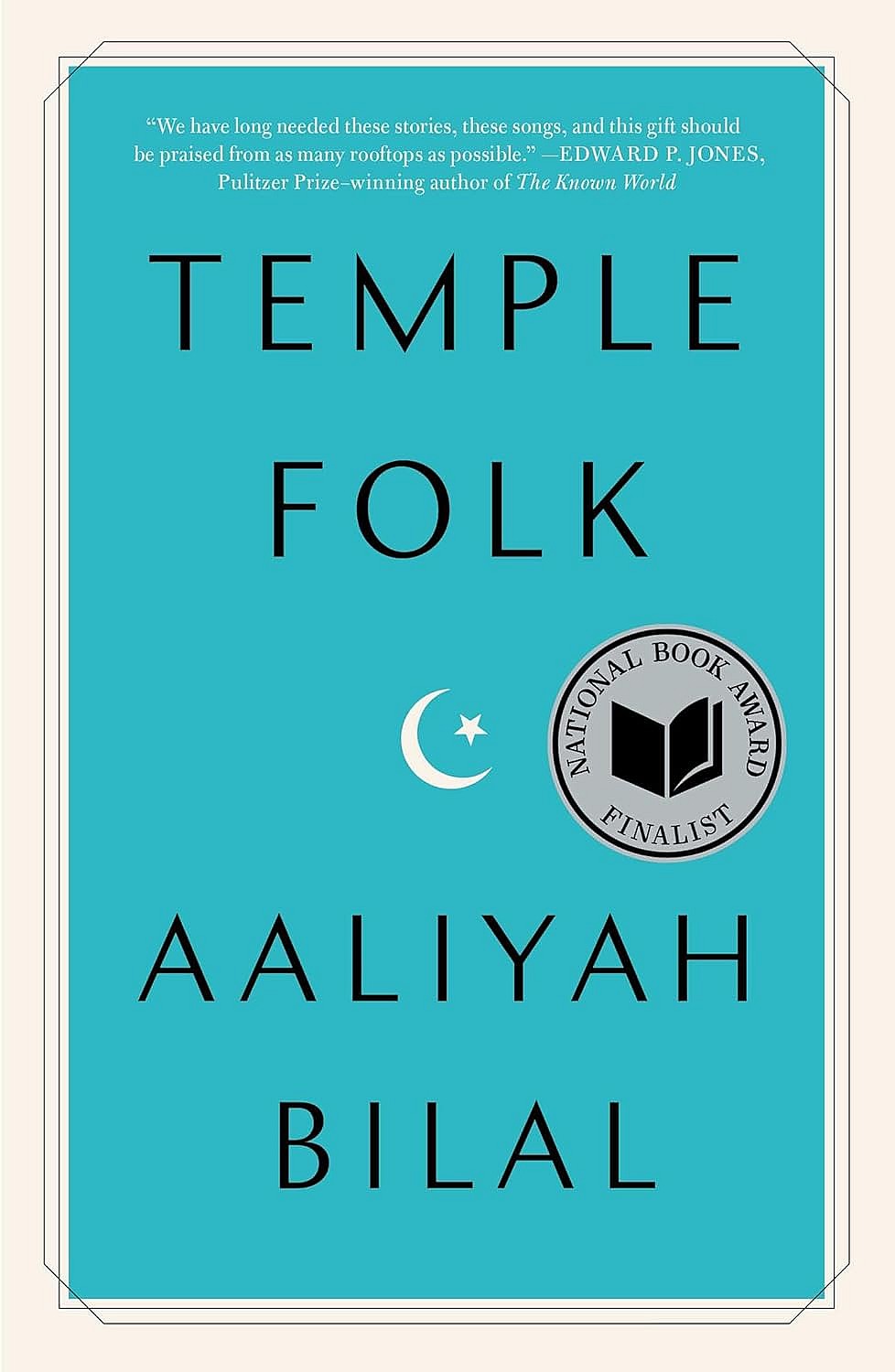

When I first heard about the short story collection “Temple Folk” by Aaliyah Bilal, I was ecstatic. Here was a book that centered the experiences of Black American Muslims — but in all honesty, I had no plans to read it. I had seemingly made peace with my decision to remain as far away from the mirror of my past. The universe had other plans for me, though. In the months that followed a New York Times article on Bilal, as her seminal text became a 2023 finalist for the National Book Award for Fiction, I had more conversations about Islam and my experiences than I’d had in years.

Then came the question of whether I was open to interviewing her. As a writer, the answer was a resounding “yes,” but there was still trepidation. Was I willing to reopen the book on my own story?

In “Temple Folk,” Bilal takes us on a journey into what it means to be a part of a movement that deserves to have more respect on its name. “The way people talk about the Nation of Islam and its culture is so uniformly negative,” she said when I spoke with her on behalf of theGrio. “And it’s so strange to me because I think, don’t you understand our history? Don’t you understand?”

I do understand. In story after story, I was pulled into my past and faced with what could have been my future. “Temple Folk” wrecked me — in the most compassionate way. As I spoke with Bilal via a Zoom call about our history with the Nation of Islam and what each of the characters in her stories meant to me and the culture at large, I found solace during our conversation — and, for those brief three hours, a sisterhood so searing and possible, even after leaving the Nation.

(Editor’s note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

Zainab Karim: First off, I want to start by saying ‘thank you.’ I immediately understood the emotional depth of what I was reading because it was my experience.

Aaliyah Bilal: Wow. Thank you. … The stories came from a deep need I had to see myself in the culture. I just have never been able to relate in a uniform way to the presentation of the Black experience as our literature makes available to us; as our film and television make available to us. There are always these touchpoints, but I never feel that’s my life — like, “That’s me.” And I always wanted to see my own experience — our experience — represented really beautifully.

And I know there have been some artistic works that have been made about Black Muslims in America, but I never really connected to that work, either. It’s like a lot of those pieces are for other people’s eyes, trying to persuade the average white American perhaps that we are decent, likable people. And I just felt like I didn’t need to be convinced of that. I just want to see myself because we have lots of rich stories to tell. That was the seed, I think, of “Temple Folk.”

ZK: I can’t even recall a book where I was absolutely so close to it, where it felt like someone had gotten my journal and started writing about my life. Especially the character Intisar in the story “Sister Rose” … I was the same age as Intisar when I left [the Nation]. … I just walked away with the hope that there was a space for me out there. And in the 25 years since, I still haven’t found one. So, after reading “Sister Rose,” I had a good long cry …

And I think that there are more Muslim women who, if they were more honest, can see themselves in a lot of these stories. We’re talking about how we left our community, and there’s this constant theme of fleeing that keeps coming up in your stories.

AB: As you can see through all the stories, this is just my bias … like, a story doesn’t work if we do not see the central character transformed. So, I’m trying to get as close as I can for all of the protagonists in the stories to a moment of transformation where they’re on the other side; where we see them in the “before” and “after” of a pivotal moment in their life. “Sister Rose” is a story that I wrote for myself. I think about every Muslim woman I know. Our stories are so similar. I’m like, “This one is just for us.” And it’s really medicine for [myself] because I walked away from my masjid feeling like, “There’s something really wrong here.” I started to get it when I was in college. Like, “Oh, they’re running game on us. This whole world is situated in a way to privilege men and to feed women this notion that by covering, we can only be respected when we are behaving that way.” Like, that’s game! And so that was when this feminist consciousness really started to grow in me.

But at the same time that was happening, I would get messages from friends, people I really respected and loved who were still in those spaces. And it just made me really come to grips with the fact that we cannot throw out the baby with the bathwater here. There are a lot of sincere, beautiful people that I would like to feel I still had access to, even though I’ve undergone this personal evolution in the way that I relate to my faith. And so that story, to me, is the most fantastical, otherworldly, truly fictional story in the book. It’s my fantasy of still being in community with people that I disagree with in some ways.

Recommended Stories

ZK: I want to touch on something else: In “Cloud Country,” your forthcoming graphic novel, you write: “Being a Muslim girl, I sensed that I lived in the sub-margins of the culture.” I’ve also felt this way. What was that feeling then, and how do you feel now?

AB: I mean, I just felt like a punchline. I felt like the first time I saw Black Muslims in the culture was [the character] Oswald Bates from “In Living Color.” You know (paraphrasing), “First of all, we must internalize the flagellation of the matter. You know, to preclude on the issue of world domination would only circumvent, excuse me, circumcise the redundancy of my, quote-unquote, intestinal tract.” Like, what? I don’t know if you remember that, but it was fun on one hand, but at the same time, it was like, I saw that echoed in so much of the representation of Black Muslims.

ZK: Yes! That was embarrassing.

AB: It’s like, we were these people who were falling short of living up to the eloquence of Malcolm, that we were the unworthy inheritors of his legacy and these idiots who would occasionally misuse big words, trying to seem smarter than we were. And then the misguided women who allow themselves to act like they live in first-century or seventh-century Arabia when they could have all of these modern conveniences.

That’s what it felt like to me growing up. It was sort of like people don’t understand that we are smart, and that we do carry this legacy. A lot of us are working class. I grew up working class. Like we are touching those realities, but there is a more dignified way to talk about our experiences rather than to just reduce us to these caricatures where we are just dumb, fumbling idiots that are gonna be in prison for the rest of our lives, you know?

ZK: Or the only way to Islam is through prison.

AB: Yeah, and so that was what I felt growing up. [But] there were advantages to being in the margins of the culture as well because you see everything more clearly than everybody else. I don’t have this pristine, indoctrinated view of America. It also connected me to the world because Muslim communities are so scattered, and we have so few friends that race can be the barrier. Race can be lowered in Muslim spaces in a way that gives you access to Indonesia, Malaysia, [the] Middle East, North Africa, you know, even Eastern Europe.

So that’s what I meant by being in the sub-margins of the culture. We’re not mainstream, but not being mainstream gives us a unique vantage point of what it means to be American.

Zainab (Zee) Khadijah Karim is an Assistant Professor of English at National-Louis University in Chicago and a writer who has published in Ebony/Jet Magazine, MadameNoire, and Midnight and Indigo, among others. She has been community-taught by other Black women writers who have helped shape her ideologies and is currently researching the power of anger and feminism through her substack The Mad Feminist.