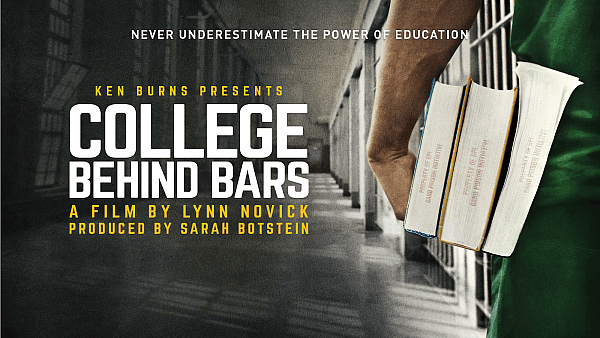

More often than not, incarcerated persons are viewed negatively in society. Ken Burns and Lynn Novick‘s documentary, College Behind Bars, is striving to change that narrative.

“Inside the walls of a classroom, you escape the walls of a cell — and you become an individual again,” says Shawnta Montgomery, speaking at the 16th commencement of the Bard Prison Initiative (BPI), in the documentary.

College Behind Bars first premiered Nov. 25, 2019 on PBS and has since then become popular among Netflix audiences. The four-part series follows the journey of men and women incarcerated in maximum and medium-security prisons across New York state over the span of four years.

The documentary shadows them as they pursue college-accredited degrees through BPI, one of the most challenging prison education programs in the nation.

To further discuss College Behind Bars and the advocacy for college access in all prisons, theGrio spoke with Dyjuan Tatro, a formerly incarcerated student of BPI who appears in the documentary. Tatro completed his incarceration in 2017.

READ MORE: Black man, denied early release, becomes first federal inmate to die of coronavirus

“One thing I am grateful for about College Behind Bars is that it complicates the narrative we see around incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people like myself,” Tatro tells theGrio.

“The filmmakers decided to introduce you to the subjects as people before you found out what they were incarcerated for. The film brings people to acknowledge the humanity of others. We view someone who went to prison for something and we say that’s who they are.”

Before incarceration, Tatro says going to college was not a part of his solid plans for the future.

“I look back, and now realize that I had this vague sense that college was something that I should have been striving for. I had no real expectations that it was something that I would actually ever do,” Tatro says.

READ MORE: Jay Z and Yo Gotti file second lawsuit against Mississippi prisons

“I vividly remember sitting in Five Points Correctional Facility and seeing a 60-minute segment on the Bard Prison Initiative come on, and there were these amazingly-smart men who were in prison just like me, wearing green like me, embarked on this rigorous educational endeavor. At that moment I decided, that was what I was going to do.”

Founded in 1999, BPI is now present in six New York State prisons. Prospective students undergo a meticulous admissions process and then enroll full-time in the same classes that they would take on Bard College’s main campus.

BPI students receive the exact education from college professors in seminar settings and are still held to the same academic expectations as Bard students outside of prison. BPI students can pursue associate and bachelor’s degrees.

College Behind Bars was filmed in real-time as students carried out their prison terms.

“There was a lot of uncertainty and pressure going into Bard. Getting into BPI is a competitive process and you don’t know what to expect,” Tatro reveals.

“I found the course material to be really challenging, and that was intimidating but I was never scared to walk into that classroom because for the first time in my life I was learning what a professor was. But it built my intellectual capacity to a level where I could keep meeting the Bard standards.”

Tatro touched on what life was like being a student while incarcerated, amongst the rest of the prison population.

“There’s a popular joke that people, like myself, who received an education in prison had all of the time in the world and that’s why it was easy for us. The reality is its the total opposite,” he explains. “Prison is not conducive to receiving an education. Everything about prison impedes your education.

“My professors assigned me 43 books for example, and I’m only allowed to have 35 books in my cell at one time. It’s those kinds of practical tensions in getting an education that you have to grapple with, on a day to day basis,” Tatro says.

“You’re on a noisy cell block and you can’t tell everyone to be quiet or shut up, you can be in class and at any given moment sent back to your cell because of a shutdown and your professor can’t be let back in. One thing I had to do was find it in myself to focus in such a way that despite what was happening, I still received a rigorous education.”

BPI offers a string of electives for students to participate in such as the debate team, which Tatro was a part of. Since 2013, the BPI Debate Union has met weekly with the college faculty coach to prepare and practice for intercollegiate debate competitions with colleges and universities including West Point, Harvard, Brown, The University of Vermont, and the historically Black Morehouse College.

READ MORE: Rep. Ayanna Pressley’s husband testified to Congress on prison re-entry reform

“It was such a great moment for us as debaters; as students; as ambassadors of the power of college in prison,” Tatro says. “That win against Harvard was so profound and it went viral. Sitting in prison and seeing the media pick up the story and getting letters and calls from friends, it inspired so many people. It also moved the general public to think differently about who incarcerated people are, and what they are capable of.”

Tatro spoke about the assumptions that his success story, portrayed through the documentary, has made people believe that prison was a positive experience for him.

“Getting an education in prison was less than ideal … I did not go to prison to get an education,” Tatro said. “I would have rathered gone to college without having ever gone to prison. But the reality is if I never went to prison and BPI didn’t exist, I’d probably never have gotten a college education.”

“Our country spends $80 billion a year on mass incarceration. That’s enough money to make tuition at all of our public colleges and universities free,” he continued. “There’s an assumption that prison did something for me — no. Bard College did something for me.”

A 2016 study by the RAND Corporation found that inmates who participated in educational programs like BPI were up to 43% less likely to have recidivism. That same study found that for every dollar invested into correctional education, nearly five dollars is saved in reincarceration costs over three years. Since filming College Behind Bars, Tatro has gone on to become the BPI Government Affairs and Advancement officer, a prison reform advocate, and a political consultant.

Tatro and BPI continue to take strides to make education accessible for more prisons nationwide, although, there are still prominent obstacles in the way of that goal. Funding seems to be the main reason behind slow progress in gaining adequate education in more prisons, according to Tatro. In retrospect, the 1994 Clinton Crime Bill ended inmates’ eligibility for federal Pell grants during the era of “tough on crime” policies. Because of that, many education programs in prisons were stripped overnight.

“For the last 20 years, BPI has been an example of the power of education in prison. We have students who have faced 15-20 years and then gone onto Ph.D. programs at Yale, Columbia, and other Ivy League universities,” Tatro says. “What the students have done is lead by example.”

Beyond the documentary, Tatro is continuing to advocate for Pell Grant funding on the state and national levels, as BPI anticipates launching more “micro-colleges” around New York City within the next five years for the “at-risk.” The documentary itself has sparked conversation nationwide, furthering the support and advocacy of the cause.

“Currently, we are working with Warner Brothers to turn the BPI vs. Harvard debate story into a movie,” Tatro mentioned. “We will continue to be out engaging around the film and lobbying on behalf of getting access to college in prison.”

College Behind Bars is available on Netflix now.