On May 10, 1967, while facing growing white backlash for demanding an end to the Vietnam War, Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke to America’s greatest shame and Black Americans’ most significant burden — racial injustice.

In King’s speech, America’s Chief Moral Dilemma he explained: “We must face the hard fact that many Americans would like to have a nation which is a democracy for white Americans but simultaneously a dictatorship over Black Americans. We must face the fact that we still have much to do in the area of race relations.”

Read More: 7 inconvenient truths white people must understand about Martin Luther King Jr.

And 54 years later, we still do.

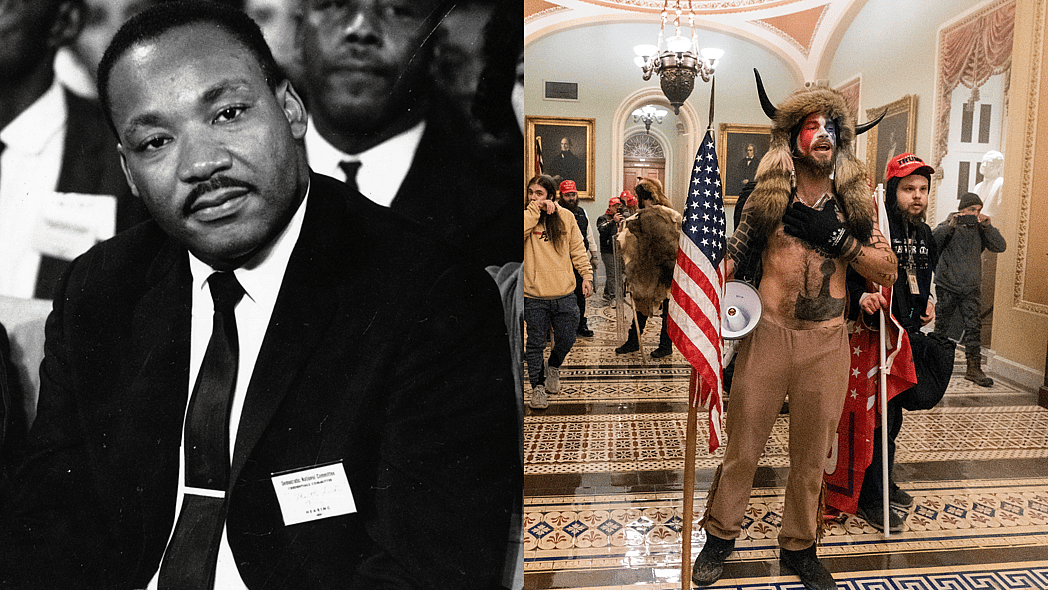

Today, as many are celebrating the life and legacy of King on what would have been his 92nd birthday, many are also still incensed at the white insurrectionist attacks at the Capitol that occurred just two weeks ago. While the violence shocked some white people — who have been raised to believe the supposed greatness of the United States — Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color (BIPOC) knew better. The only thing these attacks made clear is what Black people have been saying all along: law enforcement knows how to not use deadly force when they want to do so, it just depends on the person they are apprehending.

For far too long, reports have revealed concentric circles between white supremacist organizations (e.g. Ku Klux Klan) and the police. Nearly 15 years ago, even the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) warned of white supremacists in law enforcement. But one doesn’t need an active security clearance or FBI badge to find evidence of overt racism within both white supremacist organizations and law enforcement, or to understand the link between the two. One just needs to pay attention.

According to Brennan Center for Justice’s Hidden in Plain Sight: Racism, White Supremacy, and the Far-Right Militancy in Law Enforcement, “since 2000, law enforcement officials with alleged connections to white supremacist groups or far-right militant activities have been exposed in Alabama, California, Connecticut, Florida, Illinois, Louisiana, Michigan, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Oregon, Texas, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, and elsewhere.”

The United States’ government’s response to known connections of law enforcement officers to violent anti-Black and white supremacist groups has been strikingly insufficient. That’s why it came as no surprise when everyone watched an angry white mob “break” into the Capitol with ease and support from a few.

Read More: FBI vetting Guard troops in DC amid fears of insider attack

Since the Jan. 6 attacks, multiple photos and videos have since been released showing several police officers happily greet the rioters, take selfies, and physically remove barriers like gates. At least two Black U.S. Capitol Police officers acknowledged observing their fellow boys in blue cater to the rioters in coordinated ways.

“If they were Black, many more would be dead,” many of us stated. It isn’t that no one was killed during these attacks; in the end, 5 people were killed — a police officer was beaten, a rioter was shot, and three others died during the rampage. It’s that when Black people protest in defense of Black lives — literally pleading with law enforcement to not kill us — we are met with excessive force.

Every day. Every day in this country Black women, Black men, Black youth, Black children, and Black trans and nonbinary people experience violence at the hands of police. Every day, Black people experience violence that is bought and paid for with our tax dollars and committed in our name. Violence by white and non-Black people who are shielded by the near-bulletproof armor of white supremacy. King knew this and actively fought against this incessant violence.

Just this past summer, following the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Tony McDade, and many others known and unknown, Black people took the righteous indignation to the streets. Unlike at the Capitol, the police immediately met protesters with rubber bullets, tanks, tear gas, pepper spray, weeklong curfews, and even ran over people. This was clear all over the country, and especially in Washington, D.C. Even a newer recruit to the police force, while speaking with Buzzfeed News, pointed to a “big difference” in how his fellow officers treated the white mob compared with the way they treated Black Lives Matter protesters last summer.

Watching white supremacists with Nazi and Confederate flags storm the Capitol forced many people to reflect on their recent experiences with the police. VICE captured stories of young Black people recounting their events from protests — from a person now facing 17 charges for peacefully protesting, to being physically kicked, to SWAT blocking Black protesters in narrow alleyways, the response was night-and-day.

And it doesn’t escape me that the reason for the insurrectionist uprising was, part-and-parcel, because Trump convinced them that the election of President-Elect Joe Biden and Vice President-Elect Kamala Harris was stolen. Despite nearly 60 courts disagreeing with the Trump-Pence administration’s false claim of voter fraud, they still pushed that narrative — a narrative that fueled an already anti-Black fire. But it doesn’t stop there.

These white supremacists were attempting to warn this country what could happen if marginalized communities’ interests were prioritized in “their” country and on “their” land. Because, to them, what is this country without whiteness being front-and-center? This was not just about this past general election and their false claims, but about voting rights (and subsequent suppression) generally.

So, what does all of this have to do with King? Everything.

King taught us that the power of the vote, along with collective organizing, coalition building, and policy change could transform our systems and put BIPOC in a stronger place. And eight years before the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, King spoke to this power in his Give Us The Ballot speech: “Give us the ballot, and we will no longer plead to the federal government for passage of an anti-lynching law; we will by the power of our vote write the law on the statute books of the South and bring an end to the dastardly acts of the hooded perpetrators of violence.”

Though much has yet to be realized in large part due to voter suppression, we have made significant progress. These white supremacists, then and now, knew what King did — to deprioritize the interests of Black people one must suppress their rights at an institutional level. We are witnessing, as many who have come before us did, the backlash of perceived weakened whiteness.

In many ways, these riots occurred because many communities of color and young people exercised the right to vote. And that exercise helped to elect the first Black woman to vice presidency. With this new leadership, the Biden-Harris administration, along with a progressive House and Senate, can shape civil rights for a time: from abortion rights to COVID-19 spending packages to disability justice to healthcare to LGBTQ+ equity to criminal punishment system reform to protecting voting rights, we can solidify King’s legacy. But we must do that while simultaneously battling racial injustice, the first evil in which King spoke about until the day he was murdered.

Read More: MLK, Coretta Scott King memorial moves forward in Boston, where they first met

What these last few weeks, years, and lifetimes have taught me is that white people — including well-intentioned ones — have tremendous amounts of work to do. This is not theoretical.

White people must organize themselves and not us. They must have hard conversations with their family and friends about their entrenched anti-Blackness. They must stop focusing on how often they can get Black people to vote and instead work overtime to stop allowing their cousins to vote for white supremacists. And they must acknowledge that when Black people speak about “bad” white people that they are not suddenly immune because they haven’t been caught using the N-word.

Until then, as we commemorate King today, the question remains: what happens when white Americans have no moral arc toward justice to bend?

Preston Mitchum is the Policy Director with URGE: Unite for Reproductive & Gender Equity, a young people’s Reproductive Justice organization and Adjunct Professor of Law at Georgetown University Law Center.

Have you subscribed to theGrio’s podcast “Dear Culture”? Download our newest episodes now!

TheGrio is now on Apple TV, Amazon Fire, and Roku. Download theGrio today!