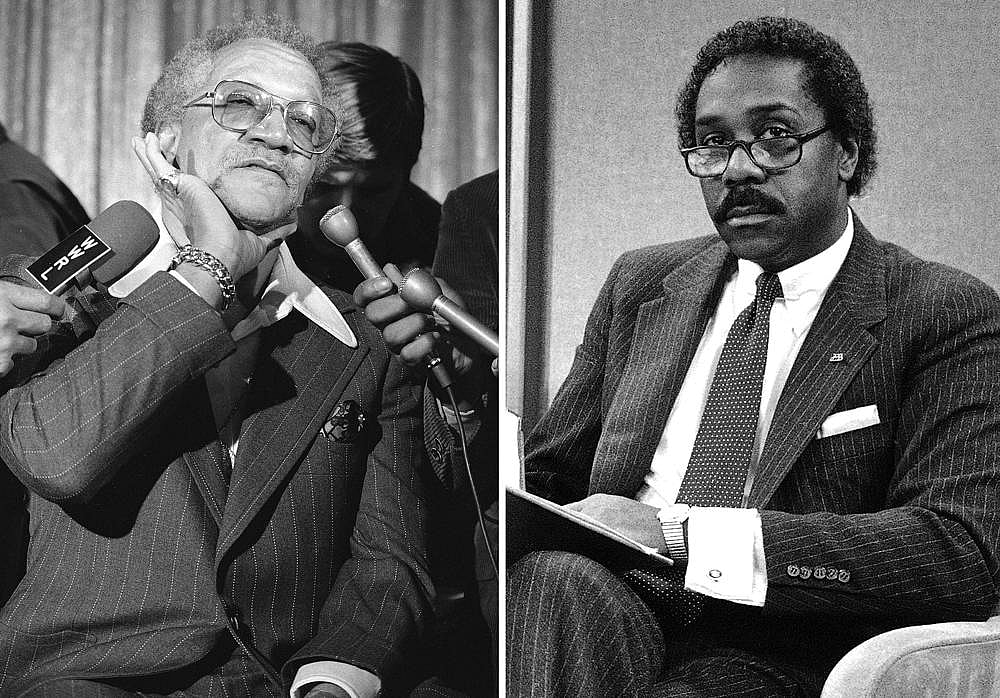

When Demond Wilson heard that Redd Foxx was going to star in a TV sitcom, the actor brushed it off as a joke.

Foxx was a killer stand-up comic, with a trademark raunchiness that Wilson figured to be a nonstarter for the timid broadcast networks that were television in 1972. It was the eve of cable, and the rise of streaming was decades away.

“It would be like bringing a dog to a cat party,” is how Wilson described the notion of Foxx invading TV in a recent Associated Press interview.

But the comedian cleaned up his act for the small screen, and Sanford and Son, with Wilson co-starring as Foxx’s beleaguered adult son, debuted 50 years ago this month on NBC. An instant ratings smash, it opened the door for other Black family shows to move into the virtually all-white TV neighborhood.

Norman Lear, who had roiled network waters the year before with the topically driven CBS sitcom All in the Family, said serendipity led to Sanford and Son. Lear and Bud Yorkin, his producing partner, were in Las Vegas when they caught a lounge act featuring Foxx.

“We met with him and came back to L.A. sky high” about creating a Foxx-centered sitcom, Lear said in an email exchange. “Miraculously, several days later a British agent, Beryl (Vertue) came to us with the idea of making an American version of a big hit in Great Britain entitled Steptoe and Son.”

“It was an instant marriage,” Lear said, and one he says Foxx didn’t resist.

“Not that he wasn’t difficult to deal with, but he was funny as hell and that made everything possible,” Lear said. Foxx, who died in 1991 at age 68, skipped part of one season amid a contract dispute with the producers.

Sanford and Son, which aired from 1972-77, revolved around widower Fred Sanford, an irascible junk dealer in the Watts area of L.A. who foisted work and insults on his long-suffering son, Lamont. Among them: “You big dummy!” which became a show catchphrase.

All episodes are on Amazon Prime Video, which licensed the series for streaming from Sony Pictures Television.

Wilson, a Vietnam veteran who had appeared on stage in New York, in films and on TV, was approached about the series after an All in the Family guest role. Wilson also learned that the producers had another possibility in mind to play Lamont.

“‘We were considering Richard Pryor,’” Wilson recalled being told. ”I said, ‘C’mon, you can’t put a comedian with a comedian. You’ve got to have a straight man.’ Dick Martin was the nut, Dan Rowan was the straight guy” on Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In, he said.

Wilson recounted joining TV veteran Aaron Ruben, who served as a producer on Sanford and Son, in Las Vegas to meet Foxx and watch his act: “I thought he was the funniest person, the most irreverently funny guy that I’d ever met in my life,” Wilson said.

Sanford and Son introduced viewers to other talented actors and comics generally sidelined by Hollywood because of their race, including cast members LaWanda Page as Aunt Esther; Whitman Mayo as Grady Wilson; Don Bexley as Bubba, and Lynn Hamilton as Foxx’s good-natured girlfriend, Donna.

Slappy White, who’d worked the comedy circuit with Foxx, appeared occasionally on the series, as did Pat Morita, of future The Karate Kid movie fame, whose character’s name, Ah Chew, and his ethnicity were punchlines for Fred.

While Sanford and Son regularly delivered such racial barbs, it rarely delved into racism or other third-rail issues — politics and abortion among them — that were central to All in the Family and its spin-off Maude.

Was that deliberate?

“Yes. We didn’t compare (All in the Family and Sanford and Son), but the characters called it like they saw it in their own neighborhoods,” Lear said in an email.

The show begat other sitcoms about working-class Black families, including Good Times, also involving Lear and starring Esther Rolle and John Amos, and the less successful What’s Happening!! from Yorkin, who died in 2015. (Lear’s The Jeffersons was rare in featuring an affluent Black couple.)

While Black viewers finally got to see a version of themselves on screen, it was mostly one limited to those in struggling neighborhoods and created by almost uniformly white producers, writers and directors at the behest of white executives.

That’s in sharp contrast to the 21st-century comedies created and steered by Black writers, producers and actors, including ABC’s black-ish, HBO’s Insecure and FX’s Atlanta, and their wide-ranging and nuanced views of Black life.

Eric Deggans, TV critic for National Public Radio, sees a “double-edged quality” to the older-generation sitcoms. They showcased performers beloved by Black audiences, and, starting with Sanford and Son, proved that a series about a family of color could be widely successful.

The comedies also were honest about depicting some real-life Black challenges, Deggans said. But they ultimately relied on racial stereotypes and settled for laughs.

The shows made poor areas “look livable and even fun, as opposed to the issues that they really faced,” Deggans said.

Have you subscribed to theGrio podcasts, Dear Culture or Acting Up? Download our newest episodes now!

TheGrio is now on Apple TV, Amazon Fire, and Roku. Download theGrio today!