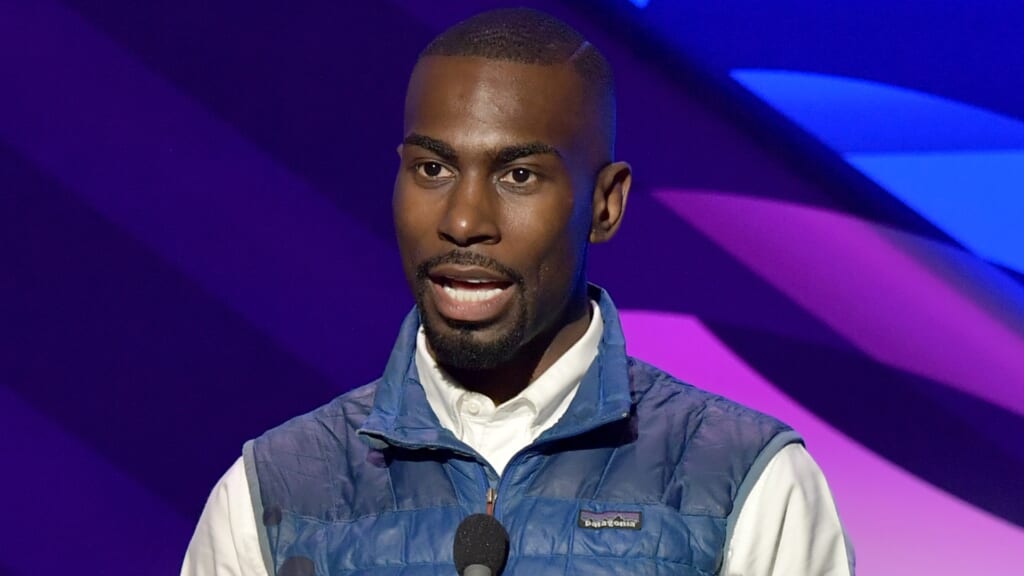

The lawsuit against DeRay Mckesson would have a chilling effect on the right to protest

OPINION: A recent ruling says a police officer can sue the activist for injuries after being hit by a piece of concrete thrown by an unknown assailant at a protest Mckesson organized.

Editor’s note: The following article is an op-ed, and the views expressed are the author’s own. Read more opinions on theGrio.

The right to protest in America is under attack, and it all involves a case against a Black Lives Matter activist. Conservative Republican judges are coming for your right to protest and making up laws to punish racial justice movements. And you should be concerned about this.

It all stems from a lawsuit that a Baton Rouge police officer filed against DeRay Mckesson for a 2016 protest Mckesson organized against the police killing of Alton Sterling. An unknown perpetrator threw a piece of concrete at the officer—who is identified as “Officer John Doe” in court filings—striking him in the face and causing “injuries to his teeth, jaw, brain, and head.” Doe is seeking damages.

In 2017, Judge Brian Jackson, a federal judge appointed by President Obama, ruled that Mckesson “solely engaged in protected speech” under the First Amendment and, as a peaceful protester, could not be held responsible for the actions of a violent demonstrator.

However, when the case was appealed to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, three out of the five judges reviewing the case—a Republican majority—ruled that Mckesson was potentially liable for the anonymous perpetrator’s attack on Officer Doe.

The problem is that the Supreme Court had already decided years earlier in NAACP v. Claiborne Hardware Co. that “Civil liability may not be imposed merely because an individual belonged to a group, some members of which committed acts of violence. For liability to be imposed by reason of association alone, it is necessary to establish that the group itself possessed unlawful goals and that the individual held a specific intent to further those illegal aims.” In other words, someone such as Mckesson can’t be held responsible for the violent actions of an unknown person attending the protest.

Months later, one of the three Republican judges who had ruled against the activist, Judge Don Willett—a Trump appointee—backtracked. In a stunning dissent, he repudiated his own vote against Mckesson. Essentially, Judge Willett said he and the rest of the court got it all wrong, and the law did not support their decision. “I have had a judicial change of heart,” Willett wrote. “Admittedly, judges aren’t naturals at backtracking or about-facing. But I do so forthrightly.

“In America, political uprisings, from peaceful picketing to lawless riots, have marked our history from the beginning—indeed, from before the beginning,” Willett added, invoking the Boston Tea Party and Dr. King’s Selma-to-Montgomery march over the Edmund Pettus Bridge two centuries later.

As nice as that sounds, Willett’s “come to Jesus” moment did not change the court’s decision against Mckesson. The U.S. Supreme Court took the case and then sent it back down to the lower federal courts to determine if the laws of the state of Louisiana—through the Louisiana Supreme Court—would allow Officer Doe to sue Mckesson.

This brings us to the most recent March ruling by the Louisiana Supreme Court, which said the officer can sue DeRay Mckesson under Louisiana law. So here we are, with a Black Lives Matter activist who maintains he did nothing wrong because he did nothing wrong, and courts kicking the can when this frivolous lawsuit should have been thrown out at the jump.

Lawsuits such as this, favored by Republican politicians, judges and police officers, are meant to have a chilling effect on free speech.

The right to protest is one of the five fundamental freedoms enshrined in the First Amendment, along with freedom of religion, speech, press, and the right to petition the government. During her confirmation hearings, Justice Amy Coney Barrett—perhaps the least qualified Supreme Court justice in recent memory, unlike the preeminent Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson—couldn’t remember that the right to protest was part of the First Amendment. That lack of knowledge or memory lapse by the handmaid judge does not bode well for the highest court and what the Constitution calls “the right of the people peaceably to assemble.”

None of this takes place in a vacuum, and the case of DeRay Mckesson is a cautionary tale. Following the police murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, America experienced a racial awakening, with 15 to 26 million people participating in Black Lives Matter protests, making this the largest movement in U.S. history. Proponents of white supremacy and the status quo decided something must be done about these uppity Black protesters and their white coconspirators.

Over the past five years, 45 states and the federal government have considered 245 pieces of legislation restricting the right to peaceful assembly, according to the International Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ICNL), with 38 laws enacted and 45 bills pending. While the supporters of such legislation claim their goal is to prevent violence, the true aim seems more insidious. These bills inflict punishment for blocking roads, ban mask wearing by demonstrators, and seize protesters’ assets. Some legislation would even protect drivers who run over and kill protesters.

Stopping traffic is a common tactic that protesters use, and apparently, lawmakers would like to eliminate these protesters and their movement.

In 2017, activist Heather Heyer was killed when a Nazi plowed into a crowd of racial justice protesters at the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville. James Fields Jr. was sentenced to life in prison for the murder, but these new laws would protect white supremacists like Fields.

In Louisiana, state Rep. Danny McCormick—a Second Amendment fan and an oil and gas executive—introduced a bill in February that would protect people who murder demonstrators during a “riot,” a vague term under Louisiana law. The legislation would “provide that a homicide is justified when committed to prevent imminent destruction of property or imminent threat of tumultuous and violent conduct during a riot.”

Concerned about this bill’s civil liberties and racial implications, some critics call this legislation the “Kill Protesters” Act and the Kyle Rittenhouse Bill—named for the white teen who shot two protesters to death and injured another in Kenosha, Wisc. And the legislation was introduced the day after a white woman named June Knightly, 60, was killed in a mass shooting during a demonstration in Portland, Ore. These people know what they’re doing.

This is why the suit again DeRay Mckesson is important, for it is part of a larger picture. Their goal is to take away the people’s right to protest and ultimately eliminate the people who protest.

David A. Love is a journalist and commentator who writes investigative stories and op-eds on a variety of issues, including politics, social justice, human rights, race, criminal justice and inequality. Love is also an instructor at the Rutgers School of Communication and Information, where he trains students in a social justice journalism lab. In addition to his journalism career, Love has worked as an advocate and leader in the nonprofit sector, served as a legislative aide, and as a law clerk to two federal judges. He holds a B.A. in East Asian Studies from Harvard University and a J.D. from the University of Pennsylvania Law School. He also completed the Joint Programme in International Human Rights Law at the University of Oxford. His portfolio website is davidalove.com.

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku, and Android TV. Please download theGrio mobile apps today!

More About:Politics