Now that we’re 9/10th of the way through Atlanta’s third season, it’s clear we’re witnessing one of the greatest seasons of any sitcom in TV history. Season 3 has been a brilliant conversation about race in America, as well as some crazy stories about the gang’s trip through Europe. It’s been funny and thought-provoking. It has given us moments unlike anything ever seen on TV.

Season 1 was a really smart and funny look at the four main characters, and season 2 expanded to be a look at the world around those characters—the ups and downs of being Black in Atlanta—but season 3 has a much broader artistic ambition. It’s a statement about America and how white and Black people are struggling to share this space and one about the confusion that comes from trying to be at home in a foreign culture. The ninth episode, “Rich Wigga, Poor Wigga,” is one of the best episodes of the season. I’m loving the episodes that are not about the gang but about white people virtually drowning in a blackened America.

“Rich Wigga, Poor Wigga” explores the question of what it means to be Black and how you judge that. It seems easy until you start diving in. For many people, the biological answer is simple, but for many, that question is messy. Are biracial or mixed people Black? If yes, we’re going by a standard created by white people to maximize their slave population. I’m not comfortable going by that standard. But the biological road also means we’re judging people based on things they were given rather than choices they made. Candace Owens and Clarence Thomas have two Black parents, but most Black people would ask, are they really Black? I mean, every brother ain’t a brother.

OK, then you could apply a cultural test that assesses your relationship to Black culture and looks at the choices that you’ve made—if you’ve chosen to immerse yourself in Black culture and its totems and institutions, then you should have no problem passing a culture test, right? Well, yes, but Blackness isn’t monolithic, and I’m sure Black folks from, say, the Midwest could come up with a cultural test that I would fail just as I could come up with a cultural test that they might fail. It gets really messy when we try to figure out who’s Black. Would Rachel Dolezal pass a Black cultural test? I don’t want to think about that.

There’s a real Twilight Zone vibe to this episode—the film stock, the black and white, the whole nature of dropping a character into a bizarre situation and seeing what he’ll do. Aaron is a biracial person who looks white and immerses himself in what we could call “white boy culture”—he loves Logan Paul and hard rock music. When he gets into an argument online, he immediately leaps to racial slurs. It’s telling that his sole interaction with his African-American peers is virtual—he has no real ties to Blackness. He’s so white-seeming that it’s a shock when it turns out his father is Black. In real life, the actor, Tyriq Withers, is biracial—his mother is Black—so he’s perfect for this role. When the wealthy businessman Robert S. Lee (which is bizarrely close to the name of the confederate General Robert E. Lee) arrives to give college scholarships to all the Black students, Aaron’s thrown into the moment of his life.

Aaron’s Blackness (or lack thereof) is put on trial—the judges sit high above him and put him under a spotlight, all of which pulls from dramatic movie trial tropes. The proceedings start with the presumption of innocence, or, I should say, the presumption of Blackness—they call him “redbone” and “high-yella.” They’re giving him the benefit of the doubt. Of course, he throws it away because prior to this moment, he’s never cared about his Blackness or about Black people, so he can barely answer the questions.

Loose Ends’ famous song “Hangin on a String” is featured throughout this episode, and it has several meanings. First, it’s a Blackfamous song. Most Black people of a certain age would recognize it right away, and most white people wouldn’t know it, so it would fit within the rubric of a test on Blackness. If the tribunal played the opening notes and said name the group that made this song, very few white people would nail it, and many Black people would if they were of a certain age. But more than that, Aaron embodies the song’s title in several ways—his Blackness, his educational future and his present sanity are all hanging on by a string.

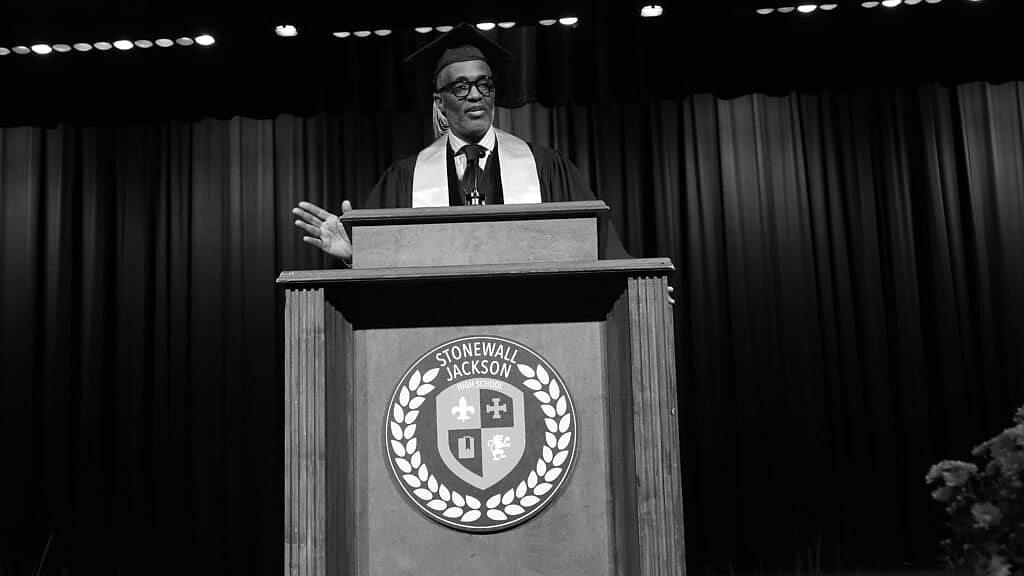

It’s crazy that one of the stars of this episode is Kevin Samuels, the controversial YouTuber who died just days before this episode came out. Whatever you think of him, in this gig, he does a great job giving us an eccentric Blackcentric millionaire. I loved his line readings—“I didn’t say what happened to that boy at Lennox Mall? I said what happened to that boy at Lennox Mall…”

I totally believed him in the role, and that’s impressive because he was not an actor. Tyriq Withers is also a YouTube celebrity, so that’s a sort of sub-theme of this episode.

I have to admit that I personally didn’t get some of the tribunal’s questions—what mixes with Hennessy? I don’t know. I’m a wine drinker. How long can chicken sit on the stove? I’m not much of a cook, so I don’t know, I’d have to call my mom. I saw the Five Heartbeats a long time ago, so I don’t recall why they broke up. I’m sure that I would pass their test. I’m all about Black culture, but I’m not sure my cultural references will exactly line up with those of these brothers. I’m uncomfortable with the idea that you could have a test of cultural Blackness that a person of any racial background could conceivably pass if they have Black family and friends, but if a lot of people of another race could pass that test, then that’s proof that the test is flawed. But that doesn’t mean that every person with Black parents should be able to pass it.

The beauty of their questions, to me, is that they didn’t go after political questions. They went into the minutiae, the nitty-gritty of Blackness—”the Holy Spirit or the Holy Ghost?” It’s not really a test you could study for like it’s Black Jeopardy. You would have to be in Black culture in order to know this stuff. Samuels’s big line comes near the end—“Getting shot by police is the Blackest thing anybody can do.” It’s funny, but I’m sorry, no. If that’s true, then the power to define who’s Black lies with the police and that’s crazy. However, as a plot twist, it’s brilliant. The Black kid gets shot, and the white-looking kid does not (of course), which leads to the Black kid being forgiven (by the Black power structure) while the white-looking kid is not, which leads to him going to jail where (of course) he falls deeper into his Blackness. He comes out with a haircut, a chain and a mouth that make his Blackness clear. Now that he’s much more rooted in his Blackness when his cute white ex-girlfriend swings by, he says he’s never been more attracted to her. Is it a reference to Black men liking white women or him feeling comfortable to spit game because he’s feeling himself as a Black man? Whatever it is, Aaron is a new man, one who does not want to be mistaken for white. His life has been changed forever—which is exactly what you’d expect in the Twilight Zone.

Touré hosts the podcast “Touré Show” and the podcast docuseries “Who Was Prince?” He is also the author of seven books.

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku, and Android TV. Please download theGrio mobile apps today!