Both May 31 and June 1 mark the 101st anniversary of the Tulsa Race Massacre, one of the country’s most renowned instances of a white mob destroying a prosperous black neighborhood and slaughtering Black people.

But the carnage that took place in the Greenwood neighborhood proved to be the culmination of unrest that began two years before. The Red Summer of 1919, which got its name from all the bloodshed, saw 25 race riots engulf the United States.

Racial tensions brought on by several factors caused that violent period in time, David F. Krugler, a professor of history at the University of Wisconsin-Platteville, told theGrio.

Black people were migrating from the south to the north. Black soldiers were coming home from WWI, and white soldiers were angered that the factory jobs they once held were now in the hands of Black workers.

White leaders were determined that “Even though African Americans contributed to the mission to make the world safer for democracy, they were not going to get democracy at home,” said Krugler, who wrote the book “1919, The Year of Racial Violence: How African Americans Fought Back.” Those leaders would use whatever method they needed to, “including mob violence.”

The first violent event of the Red Summer occurred on April 14 near Millen, Georgia, according to the National Archives. A newspaper report said white police officers stopped a car containing a group of Black men headed to a church, but someone opened fire. When the shooting stopped, six people – four Black men and two whites – were dead.

The riots happened in large cities (Washington, Chicago, Philadelphia) and small ones (Vicksburg, Mississippi; New London, Connecticut; Annapolis, Maryland). Krugler, in his discussion with theGrio, mentioned several incidents that encapsulated that deadly summer.

“The police wouldn’t protect African Americans, so I think that’s a notable feature of all the 1919 racial violence, this armed self-defense that African Americans carried out.”

Washington, D.C., July 21-25

The incident started with an allegation (with no proof) that two Black men attempted to steal a white woman’s umbrella. Police arrested a suspect. Furious, a mob of angry servicemen, armed with pistols, pipes, and more, went into an all-Black neighborhood and started beating people. Black people across the district fought back, and for four days, the nation’s capital was under siege.

“The Washington, D.C., violence is notable because it’s in the national capital,” Krugler said. “It gets a lot of attention. Here in the United States, just coming back from this war to make the world safer for democracy and it can’t ensure it for its own people because of race.”

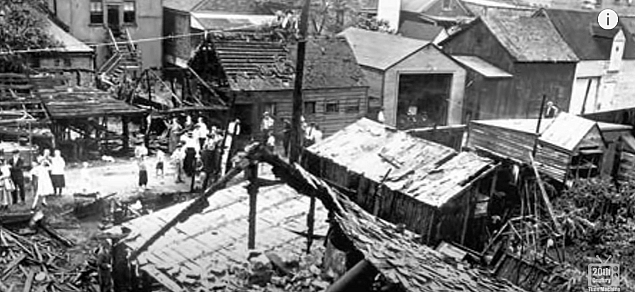

Chicago: July 27-31

Toll: 38 dead, 537 injured, scores of businesses burned or bombed, 1,000 Black families homeless.

The violence began after a white mob stoned to death a Black man swimming in Lake Michigan who drifted into an area supposedly reserved for whites. The police refused to intervene, sparking confrontations between angry residents of both races.

“In Chicago, there was a lot of white violence against Blacks. It centered in the packing houses on the South Side, with white gangs determined to terrorize Black workers and kill them. And they do, to drive them from those jobs,” Krugler said. The mobs also drove “African Americans from white neighborhoods on the border with the so-called Black Belt. Very targeted evictions that sparked the week-long violence in Chicago,” he said.

When it was over, historians called Chicago the worst race riot of 1919.

Knoxville, Tennessee, Aug. 30-31

Toll: Two dead, hundreds wounded

After a white woman was shot in her bedroom, police quickly identified a well-known Black man, Maurice Mayes, as the suspect. Angry white mobs formed, and members of the National Guard, charged with quelling the disturbance, joined in. The group started shooting into buildings that contained Black people, who fought back. On the morning of Aug. 31, several hundred additional Guardsmen restored order. While the official death toll stands at two, historians believe it to be much higher.

“That’s part of the pattern of 1919, this white rage that is met with Black defense and an effort to protect lives and property,” Krugler said.

Omaha, Nebraska, Sept. 28-29

Toll: 3 dead

A crazed mob broke into a courthouse on Sept. 28 to go after Will Brown, a Black man accused of raping a white woman. Reports of the alleged crime agitated the crowd, containing as many as 15,000 people. The group set upon the courthouse, looted nearby stores, and grabbed Brown. They lynched him, shot him, tied his body behind a car, and set it on fire. Two white men died in the riot.

Elaine Race Massacre, Arkansas, Sept. 30- Oct. 7

Toll: Est. 237 dead

Black sharecroppers wanted to unionize for better wages and working conditions, and that became the catalyst for the slaughter in Phillips County, Arkansas, known as the Elaine Race Massacre.

A group of white men showed up at a union meeting and fired shots, which were returned. One white man died and another was hurt, resulting in an angry mob targeting Black sharecroppers. The governor called in 500 soldiers from Camp Pike and gave them the OK to shoot to kill if necessary.

During that week, authorities, supplemented by vigilantes, rounded up men, women, and children, took their weapons so they were defenseless, and gunned them down.

“When the governor called in the troops, they’re basically given the order, do whatever you have to do, and they take that as a license to murder African Americans,” Krugler said.

The last riot of that year, according to the Archives, occurred on Nov. 30 in Lake City, Florida. A Black man alleged to have attacked a white woman was found hanging from a tree.

But flipping the calendar to 1920 didn’t end the violence and set the stage for Tulsa, which Krugler said was a culmination of what happened two years earlier.

“It reflects the pattern we see in 1919, extending in 1920, and Tulsa,” he said. “There is an incident, a fictionalized one, that stirs up white anger. So we have that parallel. “

But there’s more.

“The real target of white anger is Black prosperity, and that also occurs in 1919,” Krugler said.” One of the factors in Washington, D.C.’s violence is this white resentment that there’s an emergent Black middle class. And there were just a lot of whites who couldn’t stand that.

“That’s what’s going on in Tulsa. They want to burn Greenwood to the ground because of Black prosperity,” he said.

The National Archives has a number of tools that show the history of the Red Summer, including a timeline and an interactive map.

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku and Android TV. Also, please download theGrio mobile apps today!