Editor’s note: The following article is an op-ed, and the views expressed are the author’s own. Read more opinions on theGrio.

(Warning: Contains major spoilers for “Wakanda Forever.”)

I understand that the whole “Black Panther” movie franchise is a quasi-religious experience for Black people and thus it is not to be criticized. But it’s a movie, and I have a critique. But no, I can’t possibly say anything about “Wakanda Forever” that’s not complete praise because we are so deeply invested in the story of these characters that we love them like sisters and brothers and aunts and uncles.

The first “Black Panther” was such a gigantic cultural event that it imbued this series with a power that’s unusual in the world of culture — that film was more than a movie to us. It gave us images we needed to see of Black power, Black brilliance, Black beauty. The story of an African nation as a global superpower imbued us with a greater sense of pride and self-love to the point where the chronicles of Wakanda were like an important spiritual fuel for Black people. It was as if watching the story of this amazing African nation helped heal some of the intergenerational trauma of being stolen from Africa. I’m with you on all of that. I have worshiped at the church of “Black Panther,” and I continue to. But in “Wakanda Forever,” something is awry.

No, forget it. I can’t possibly say anything is amiss in a movie like this, one that takes on extra significance as it beautifully honors both Chadwick Boseman, a great actor, and King T’Challa, an extraordinary and beloved character. Rarely has a movie had a real-life death hovering over it like this one, and that’s why “Wakanda Forever” is probably the saddest action movie you’ll ever see. That’s not a criticism. That’s just real. (I’m still working up to the critique.) You’re meant to cry in the beginning as they say goodbye to T’Challa, and you’re meant to cry when Queen Ramonda dies, and you’re meant to cry when T’Challa’s son arrives. I did. It’s a powerful choice to make sadness such a crucial part of this important film — sadness can envelop an audience like few other emotions, and it can deepen our attachment to the characters.

I loved “Wakanda Forever” and will see it again, but I do have an issue. At the heart of “Black Panther,” the first film, was an ideological and physical battle between T’Challa and Killmonger, which was symbolic of the Black community arguing and/or warring in the 1960s over what tactics we should use in the battle against white supremacy. They were like Dr. King and Malcolm X tussling over how to get free. They were arguing over whether or not to approach the world from a diasporic point of view. That intraracial argument about “where do we go from here?” was powerful and instructive. It was Black people working out what our future would be and growing from the conversation.

In “Wakanda Forever,” the major conflict comes from outside the community, and there’s a battle between Wakanda and Talokan. When we are introduced to the amazing underwater community of Talokan we see the many Mesoamerican elements of Talokan. The nation is filled with people who were forced out of Central American countries by colonizers. They are played by actors from Mexico, Venezuela and other Central American countries. Talokan’s leader, Namor, speaks in the ancient Mayan language. This is partly about diversity — bringing in Latin American characters and influences in order to welcome in that audience, setting up a future movie that focuses on Talokan, which the studio would expect to do very well with Latino and Hispanic people. That’s cool, but the path to that diversity means having Wakanda and Talokan be at war for a large portion of the movie.

Watching this war, I couldn’t help but think that “Wakanda Forever” was, in part, about a war between Black and brown people. People of color at war with each other? Really? That’s what they chose to give us? Even though the film itself provides ample reasons for Wakanda to be angry with Western nations? What?

This is a movie that includes references to the history of major Western nations stealing from African nations. Early on in “Wakanda Forever,” we see French soldiers invading Wakanda in a brazen attempt to steal vibranium, which recalls the way France, England, Spain, America and others have stolen critical resources from the nations of the diaspora. The colonizers are working hard to steal from and to destabilize Wakanda. Yet the film does not have Wakanda truly confront the colonizers. Wakandans call themselves the most powerful nation in the world, yet their response to being invaded by France is performative — they parade the captured soldiers into the United Nations to show their power and their mercy. This is not what a major nation would do. If some nation sent soldiers into the United States to steal something — we don’t actually make anything worth stealing, but it’s a metaphor; stick with me — that act of aggression would be met much more forcefully. The film makes it clear that colonizers are bad, they’re thieves, and they’re duplicitous, but Wakandans don’t even consider fighting against them or teaching them a lesson. This is a strange omission.

I also find it discomforting that the main American character in the “Black Panther” series is a friendly CIA agent. What? An intelligence operative who Black people can trust? Huh? This runs counter to the history of how the CIA and the FBI and the American government have treated Black revolutionaries and African nations for decades. They have basically waged war on us, but “Black Panther” is teaching us that there are some CIA agents that you can believe in. In many ways, the CIA and the FBI are high-level cops and surely Ryan Coogler who made “Fruitvale Station” agrees with us when we chant ACAB. But his films say well, not all cops…

I just want every bit of the stories about Wakanda to truly live up to the revolutionary tone of the films. Making Africa and Africans look so beautiful and powerful and brilliant on the silver screen is a truly subversive act that helps liberate Black minds. “Wakanda Forever” is, like “Black Panther,” a film we need in our soul, and while most of it is empowering, there are some script choices that could’ve been sharper.

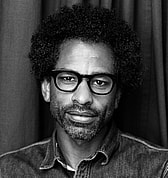

Touré is a host and Creative Director at theGrio. He is the host of the podcast “Toure Show” and the podcast docuseries “Who Was Prince?” He is also the author of seven books including the Prince biography Nothing Compares 2 U. Look out for his upcoming podcast Being Black In the 80s.

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku, and Android TV. Please download theGrio mobile apps today!