I decided to take the plunge. After years of watching upbeat, inspirational commercials and listening to long tales over the dinner table about my family lineage, I was ready to get a DNA test. As the only child of two pretty skeptical parents (“You can’t trust anybody!” is my Bronx-born mother’s favorite saying), turning over a sizeable sample of my genes to an outside company was a pretty large act of trust. But sometimes in life, your questions outweigh your fears. There are just things you need to know, and in this case, only spitting into a test tube could give them to me.

The questions I hoped to answer by getting a DNA test were fairly common ones for a lot of Black Americans whose ancestors survived the Middle Passage only to be scattered across the United States and forced into brutal labor on this land — where did my African ancestors actually come from? What regions of America did we all end up in? And did I really have those Cherokee Native American ancestors my daddy’s side of the family claimed to have? There was a time when these answers were all known to Black families. In fact, the term “griot” means storyteller. In West Africa, the griot was a revered person who was the keeper of community histories and kept them alive through oral storytelling.

I knew through the stories passed down on my father’s side that we were originally from South Carolina and Florida; a family that migrated north like many African Americans in the early 1900s. But my story was made much more complicated by my mother’s side. My mother is Puerto Rican, a Nuyorican (or New York Puerto Rican) by birth. Puerto Ricans are commonly (and to some critics mythically) believed to be a “mix” of many races and groups — white European colonizers from Spain; indigenous Taino natives who originally inhabited the island, and African ancestors who were stolen, enslaved, and forced to work the island’s land against their will. Some Puerto Ricans are no mix — just straight up Black and straight up white Latinos — but in the case of my mother, she actually was what some call a mestiza.

So what would I learn about my mother’s contribution to my DNA and given how racially ambiguous she looked, what would be the percentage breakdowns of her background? How much African ancestry did she, too, carry in her blood?

After taking two DNA tests, one from AncestryDNA and one from 23andMe, I finally got my answers. And the experience has provided me with some important pieces of advice for anyone who wants to take this journey on their own. Here are my top takeaways:

- Your DNA results may turn prized family stories into myths.

All my life, I’d heard that we had a long-lost ancestor who was Cherokee and had married into our Black family. While this ancestor may have existed, when I actually looked at DNA results, I didn’t personally have Indigenous North American ties showing up.

Nicka Sewell-Smith, a genealogist from Ancestry.com who helps people find their family stories, says this is common.

“‘She could sit on her hair. She had high cheekbones…’ That’s like the most pervasive story I hear,” says Sewell-Smith of some African Americans who recount family stories about their past ancestors.

While some of these stories are definitely true for certain individuals, confirming your family’s story allows you to know what’s actually true for you and your bloodline.

While I may not have had Indigenous North American DNA, what I did have was nearly a tenth of my DNA from Indigenous Puerto Rico, which points back to the Taino people who’d been killed in large numbers by the Spanish. Sometimes there’s more to be found in the surprises than confirming what we thought we knew.

- Historical documents are just as important as your DNA.

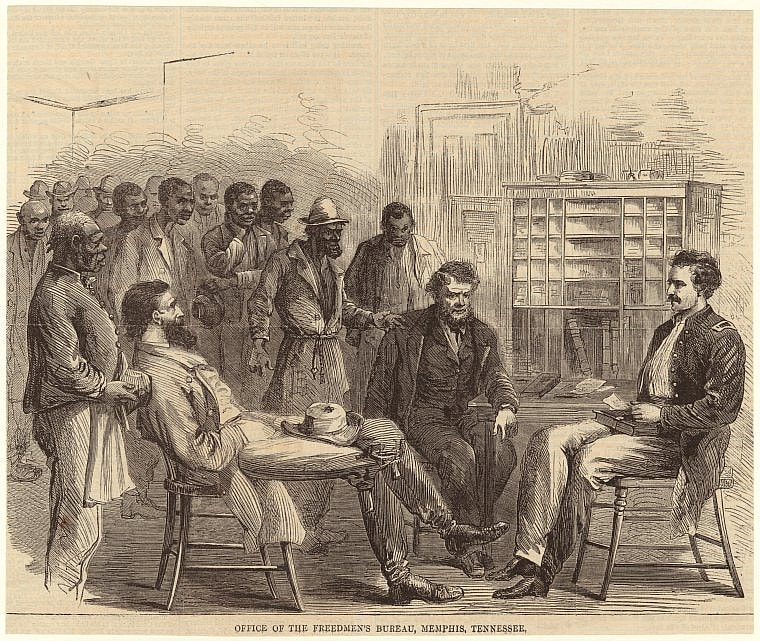

While most of our ancestors didn’t spit into a tube to take DNA tests, they did leave behind important historical records of their existence: death certificates, birth certificates, marriage certificates — and in the case of some of the enslaved people who lived through Emancipation — Freedmen’s Bureau contracts.

Sewell-Smith discovered that one of my ancestors purchased land for the first Negro school in his Florida town. She also found my ancestor Beachmon Alford worked on the M.B. Gandy plantation in Darlington, South Carolina. Beachmon’s name appears right on a Freedmen’s Bureau contract that lists strict rules he must follow in order not to be financially punished by having to give up bushels of crops. The revelation was incredible — something I never would’ve known without the skill of a researcher helping me find that document.

It would lead to the discovery of his death certificate and other documents that helped me know he was in fact here and he mattered. Which leads to point No. 3…

- You may experience emotions you weren’t expecting.

Learning that my ancestor was enslaved only confirmed what I’d logically concluded about my British surname, Alford. This young man had been stripped of choosing his name or destiny to work for a European slave master, and yet his blood still lived on through me. I felt both hurt for his suffering, proud of his resilience, and angry at the injustice of what he lost all at once. It’s one thing to talk theoretically about descending from enslaved Black people — it’s another thing to share a name with a human being you can name.

Issues like reparations, housing, and the criminal justice system all carry new meaning. I feel like I am walking through the world with the right set of prescription glasses and 20-20 vision after years of only seeing close enough and being fine with it.

Be prepared to go through your own journey after having your eyes opened to your family’s past and ensure you have a support system to lay it all out on the table.

- You may find relatives you didn’t know existed — or always hoped did exist.

Another reality of DNA testing is that you may find people in the present day who you are related to. That goes for cousins, nieces, great-aunts, great-uncles…but also sometimes family members who are way closer.

“People discover siblings, parents, all of that,” says Sewell-Smith, pointing to the DNA tab on Ancestry which displays DNA matches. “What it does is it takes your kit and it compares it to all the 22 million-plus people who already tested on Ancestry, and it gives you a degree of relatedness between you and all those folks.”

In the case of an individual looking for a long-lost parent, this can be a dream come true. It can also mean seeing yourself in a whole different way. Similar to social platforms like Facebook, you can connect with and send messages to newly found family members if you wish to be contacted. So be ready to meet a whole host of new first, second and third cousins you can invite to the BBQ this summer!

- Your DNA percentages may tell the story of how Africa was colonized.

One of the most striking realities of taking a DNA test is seeing the various countries and regions in Africa that are represented in your blood. While being in America has made many of us without a specific homeland choose the umbrella term of “Black,” your DNA can show you how your Blackness breaks down.

In my case, the majority of my DNA comes from Nigeria, Cameroon, Congo, Senegal, Ivory Coast and Ghana.

It’s a historical reality that comes from the transatlantic slave trade, where an estimated 13 million Africans from all over the continent were stolen and trafficked, with 2 million dying in the process.

People who live in Africa today and have taken DNA tests, provide the modern-day “match” so to speak, that confirms our relation.

“Most people, when they think about DNA testing, they think about the percentages,” Sewell-Smith tells theGrio. “The breakdown from different regions across the world — that’s one aspect of the DNA testing, which uses reference panels and additional research that is done based on the people who have tested. And it zeroes in on certain locations across the world that your ancestry comes from.”

While we have current-day maps and strict geographical divisions by country, Sewell-Smith says that wasn’t always the case.

“These areas, these countries, were less rigid and more fluid. People also migrated to different places,” she says, explaining why some people’s DNA percentages appear over wide regions of Africa.

As more individuals take DNA tests, percentages on your DNA report may shift slightly to reflect the more detailed DNA dataset.

“It’s going to get more refined,” Sewell-Smith tells theGrio. “As more people test and as we study the database more, it’s going to drill down much more precisely on a respective region.”

Overall, no matter what you find, just know that by contributing your DNA, you may be helping someone else find their full story, too. Either in the present day or the far-away future when they are looking back to see the kind of ancestor you were.

Knowing where I come from on both sides of my family has given me both answers and an increased confidence in myself because of all they’ve endured.

“The victory is the fact that we can tell their stories now,” says Sewell-Smith. “Despite the fact that they may not have been able to read and write, we can now we have platforms like this one where we can shout their names out.”

“We can talk about these names that maybe were lost to time, but they were always embedded deep inside of our hearts…As we find the information, that one thing that we owe them is to keep their names in the mouths of our family members and to pass it down to future generations.”

Natasha S. Alford is VP of Digital Content and a Senior Correspondent at theGrio. An award-winning journalist, filmmaker, and TV personality, Alford is writing her forthcoming book “American Negra.” Follow her on Twitter and Instagram at @natashasalford.

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku, and Android TV. TheGrio’s Black Podcast Network is free too. Download theGrio mobile apps today! Listen to ‘Writing Black’ with Maiysha Kai.