How the GOP’s presidential hopefuls could benefit from the Black histories they’re banning

OPINION: If these politicians are, in fact, fighting for a "more perfect union," there is no education more powerful than Black history for enabling the imagination to envision the society that could be.

Editor’s note: The following article is an op-ed, and the views expressed are the author’s own. Read more opinions on theGrio.

In the GOP’s rebuttal to President Biden’s State of the Union speech earlier this month, newly elected Arkansas governor, Sarah Huckabee Sanders, declared, “It is time for a new generation of Republican leadership.” Explaining just what direction this new generation ought to be taking, she proudly announced some of her first executive orders upon taking office, orders that would in her words, “ban CRT, racism and indoctrination in our schools.”

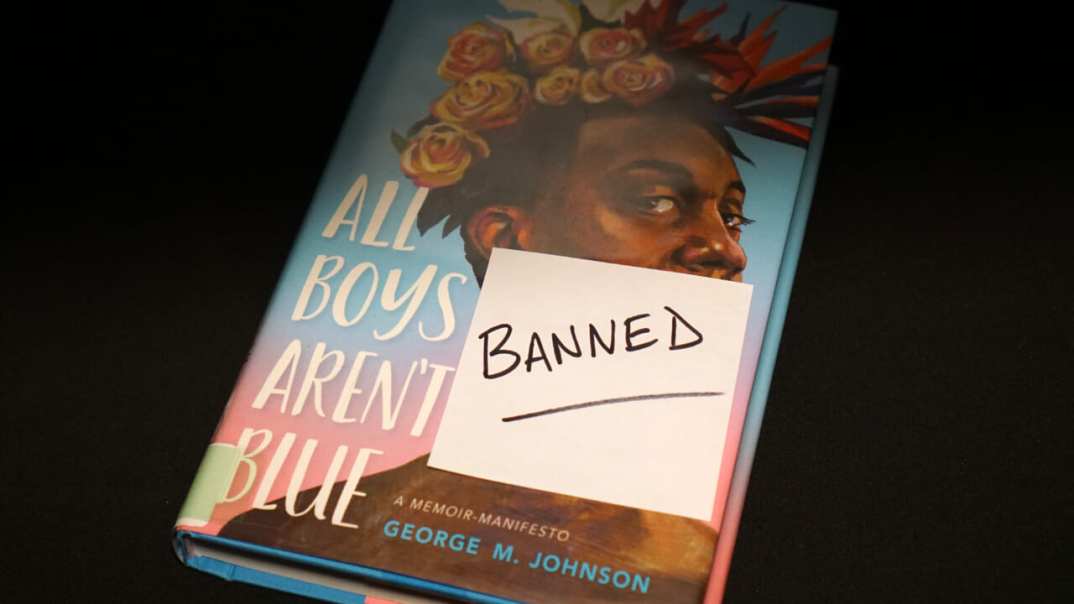

In fueling the “anti-woke” culture war, Gov. Sanders joins GOP figures like Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis and former South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley who are angling for the Republican nomination to the presidency by playing up the alleged threat of racial education. Haley herself tweeted on Jan. 30, “CRT is un-American,” warning, “Critical race theory is going to hold back generations of young people.” Meanwhile, DeSantis has proudly proclaimed Florida’s Stop-W.O.K.E. Act as the model for prohibiting education that would make students “feel guilt, anguish or any form of psychological distress” and promised to prevent funding for college programs on diversity, equity and inclusion. Through these political maneuvers, it is unclear whether celebrations of Black History Month itself are even permissible.

Yet the right-wing “anti-woke” culture war did not begin with the recent moral panic around racial education. In my forthcoming book, “The Struggle for the People’s King: How Politics Transforms the Memory of the Civil Rights Movement” (Princeton University Press), I find that limiting the public’s understanding of the racial past is a long-standing political strategy catalyzed through the backlash to the gains of the civil rights movement. Historical revisionism is a central way that right-wing groups have worked to preserve their system of power.

Increasingly since the 1980s, white, right-wing social movements, from family values coalitions to alt-right groups, have distorted and remade the story of the racial past by voiding it of its context, meaning, and power. Through a revisionist past, right-wing groups can portray themselves as the newly oppressed minorities under multicultural democracy. These revisionist histories weaponize the racial past, targeting and discrediting education in racial and social justice as forms of so-called “reverse racism.”

Revising the racial past has not only been a rhetorical move. It has been used to justify the rollback of civil rights gains, from the repealed provision of the Voting Rights Act (Shelby County v. Holder) where Justice Scalia called the provision protecting minority voting rights a “racial entitlement” standing in the way of the political process, to attempts to repeal affirmative action in college admissions (Fisher v. University of Texas Fisher v. University of Texas, and the current cases before the Supreme Court, Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard and Students for Fair Admissions v. University of North Carolina). Through this alternative reality, merely learning about America’s racial history — learning about the persistence of racism — can itself be framed as victimizing white Americans.

These political strategies have already had consequences. Even before the anti-CRT bills of late, school curricula across the nation intentionally wrote out or revised American legacies of settler colonialism and chattel slavery. A 2018 report by the Southern Poverty Law Center identified disturbing patterns in youth knowledge of America’s racial past. Only 8% of high school seniors could identify slavery as a central cause of the Civil War. Many did not know slavery ended with an amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Less than half understood that slavery was legal in every colony during the American Revolution.

The histories we learn are central to the stories we tell ourselves as a society about how we arrived at this moment and where we go next. The irony of the GOP’s performative battle against educating children in America’s full and complex racial past is that these presidential hopefuls themselves would benefit from understanding the Black histories they are working to ban.

The legacies of Black history show us that a critical education expands our conception of what is possible. A critical education teaches us how to understand our individual experiences within a larger sociohistorical context, illuminating our interconnectedness to one another across boundaries, borders, and time. If these politicians are, in fact, fighting for a “more perfect union,” there is no education more powerful than Black history for enabling the imagination to envision together the society that could be. Ultimately, the stakes of distorting the racial past are not only the strength of our social fabric and the viability of our democracy. The stakes are also our collective survival. As Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. said in a 1964 sermon, “Nothing in the world is more dangerous than sincere ignorance and conscientious stupidity.”

Hajar Yazdiha is an Assistant Professor of Sociology, University of Southern California Dornsife College of Letters, Arts, and Sciences. Her research examines the mechanisms underlying the politics of inclusion and exclusion as they shape intergroup boundaries, ethno-racial identities, and intergroup relations.

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku, and Android TV. Please download theGrio mobile apps today!