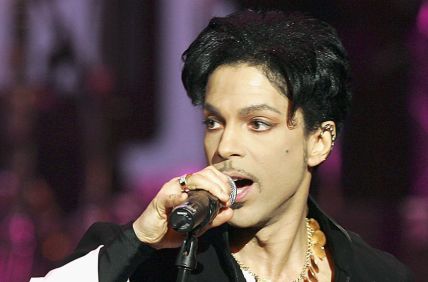

Prince and hip-hop: A ‘strange relationship’

OPINION: Part Two of theGrio’s four-part series on Prince examines the complexities of the iconic artist’s reaction to hip-hop and rap during his career.

Editor’s note: The following article is an op-ed and the views expressed are the author’s own. Read more opinions on theGrio.

When one thinks of Prince, one will tend to recall a master of music who could fluidly speak the dialect of various genres and subgenres that make up the language of music. Does one think of hip-hop when thinking of Prince? Not likely.

Prince’s androgynous nature was in direct contrast with hip-hop’s outward masculinity. In truth, Prince and hip-hop culture had much more in common than one would think. Aside from maintaining a confident sense of masculinity and virility, Prince approached music the same way those in hip-hop did.

Prince himself expressed that he wanted no part of hip-hop at first. But as history illustrates, it was a relationship that he could never fully accept nor entirely ignore.

In 1983, Russell Simmons was in a recording studio with Run-DMC and producer Larry Smith recording a song called “Sucker M.C.s.” Built on just a drum beat and no melody accompaniment, Simmons said this is the song. The following year, Prince was in a studio recording “When Doves Cry.” After listening back, he removed the bass. Two pivotal moments in music history were created from the same sense of creative insurrection against Black music tradition.

Perhaps without knowing, Prince possessed the intangibles associated with hip-hop: rebellion, ingenuity and brash confidence. Aside from these elements, his production style paralleled a direction that rap music and hip-hop were heading toward.

Prince dabbled in hip-hop during the early 1980s. Perhaps while noticing the underground phenomenon of rap, he saw fit to challenge himself somewhat or just wanted to try something new for the sake of a lark. He rapped on his 1983 B-side “Irresistible Bitch” and produced Sheila E.’s “Holly Rock,” featuring her rapping throughout the song.

Aside from the rapping element, Prince’s expertise in drum programming on the Linn LM-1 drum machine was a precursor to where rap production would wind up later in the decade. The repetitive programming on “When Doves Cry” certainly informed the kind of patterns that producers like Marley Marl would do in the late 1980s. Meanwhile, the skittish hi-hats and heavy bass drums on songs like “Something in the Water (Does Not Compute)” and The Time’s “777-9311” would predict what trap music would sound like in the 2000s.

The concurrent development of Prince and hip-hop music found both entities traversing similar pathways, though mostly in spirit. However, shortly after the release of his acclaimed 1987 double album “Sign ‘O’ the Times,” Prince began to veer away from hip-hop as he noticed popular music trends were changing.

By 1987, rap music had infiltrated mainstream music. With Run-DMC, Eric B. and Rakim, LL Cool J and others getting praise from the public for their innovation, Prince, who was experimenting with rap just a few years before, violently dismissed it. Late that year, he made plans to release “The Black Album” as the follow-up to “Sign ‘O’ the Times.” While the album was shelved at the last minute, it became a bootleg classic, revealing a diss against hip-hop:

“Riding in my Thunderbird on the freeway

I turned on my radio to hear some music play

I got a silly rapper talking silly s–t instead

And the only good rapper is one that’s dead… on it.”

L. Londell McMillan, Prince’s former lawyer and organizer in his estate, explained that Prince’s competitive nature fueled his aversion to rapping and hip-hop production, especially as the genre’s popularity increased.

“Prince is very competitive,” McMillan told theGrio. “He’s a musician’s musician, and a lot of hip-hop came by the turntables, digital tech, technical production more so than initially with the instrumentation.”

Soon enough, Prince would come around again via his inner circle. Tony M., a dance and choreographer with Prince in the early 1990s, played Digital Underground’s “The Humpty Dance” during rehearsal, rapping it word for word as Prince walked in. Something about that song piqued Prince’s interest. Shortly after, Tony M. was Prince’s featured rapper in his band, the New Power Generation.

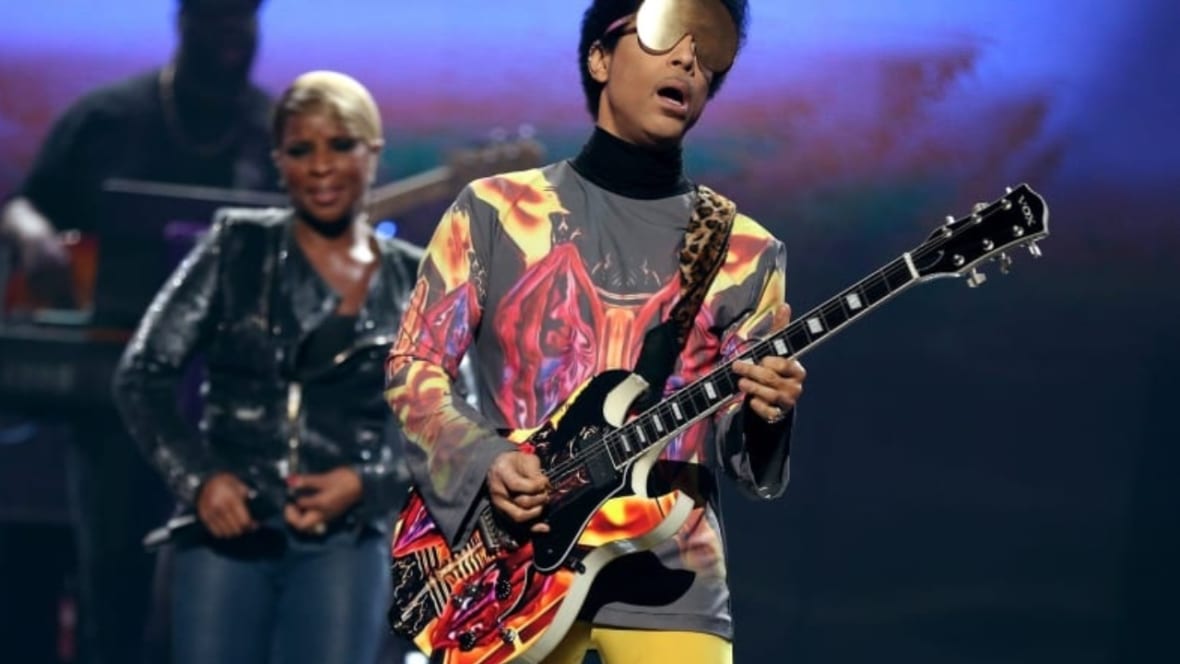

Prince’s interpretation of rap and hip-hop culture and aesthetics blossomed on his 1992 “Love Symbol” album. He fully committed to making rap on songs like “My Name is Prince,” “Sexy MF” and “Pope” from his 1993 compilation set, “The Hits.” He even experimented with sampling, using his own “I Wanna Be Your Lover” and a section of Bernie Mac’s “Def Comedy Jam” routine on “My Name is Prince” and “Pope,” respectively.

Wearing a hat with chain links covering his face while rhyming into a microphone shaped like a handgun might have been seen as peculiar to the hip-hop community, but Tony M. offered context at Paisley Park’s Celebration 2023. He stated that Prince advised him to avoid mimicking New York or West Coast rap since Tony was from northern Minneapolis. Prince instructed him to find his identity, giving the unorthodox cadences of him and Prince in “Willing and Able,” “My Name is Prince” and “Sexy MF” much more meaningful context.

Chuck D, who spoke about his relationship with Prince at Celebration 2023 on Friday, mentioned that the lyrics from the “Sign ‘O’ the Times” single informed his approach to rhyming when crafting the classic Public Enemy albums “It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back” and “Fear of a Black Planet.”

“A sister killed her baby,

‘Cause she couldn’t afford to feed it,

Yet, we’re sending people to the moon,

In September, my cousin tried reefer for the very first time,

Now he’s doing horse; it’s June.”

The Public Enemy frontman said that “Sign O’ the Times” lyrics caused him to “maximize my intent” when writing. Soon enough, Chuck D and Prince would meet and become friends.

Chuck D explained that Prince would ask him about rap and what made it so potent to the public. Chuck schooled Prince, telling him, “Hip-hop is an umbrella of creativity,” breaking down how rap is only an element of a larger art form.

“Prince had a very unique relationship with hip-hop,” said McMillan. “He didn’t initially embrace it as much at first, but he later became much more of a supporter of the art form in the culture.”

Once Chuck D — and later, Doug E. Fresh — helped Prince understand the elements of hip-hop culture more fully, he could put the music in context and embrace it more organically. Chuck would rap on his 1999 album, “Rave Un2 the Joy Fantastic,” while Prince would sample Craig Mack’s “Flava in Ya Ear” on the album’s lead single, “The Greatest Romance Ever Sold.”

Prince even included Digital Underground frontman Shock G’s remix of his “Love Sign” on his 1998 “Crystal Ball” album — a full-circle moment from when Tony M. played “The Humpty Dance” for Prince years before.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s onward, Prince continued to implicitly put live musicianship and singing on a pedestal compared to hip-hop. In interviews, he would criticize rappers and R&B singers who lip-synced and depended on sampling too heavily. So, even with his education from the pillars of the culture, Prince still resisted the genre.

Despite Prince’s public commentary on the subject, he was still greatly admired by hip-hop artists like Chuck D, Doug E. Fresh and Nas, who said Prince educated him on the importance of owning your masters.

“They loved him and supported him,” McMillan said. “Not just because of his music and how special his music was, but also because of what he stood for culturally, something that hip-hop has always stood for, which is being rebellious, innovative and free.”

Prince’s relationship with hip-hop may have never been entirely resolved when he died. Regardless, his incorporation of hip-hop and rap elements in his music during crucial transitional periods of his career showed that he was still open-minded when exploring all facets of music.

Matthew Allen is an entertainment writer of music and culture for theGrio. He is an award-winning music journalist, TV producer and director based in Brooklyn, NY. He’s interviewed the likes of Quincy Jones, Jill Scott, Smokey Robinson and more for publications such as Ebony, Jet, The Root, Village Voice, Wax Poetics, Revive Music, Okayplayer, and Soulhead. His video work can be seen on PBS/All Arts, Brooklyn Free Speech TV and BRIC TV.

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku, and Android TV. Please download theGrio mobile apps today!

More About:Entertainment