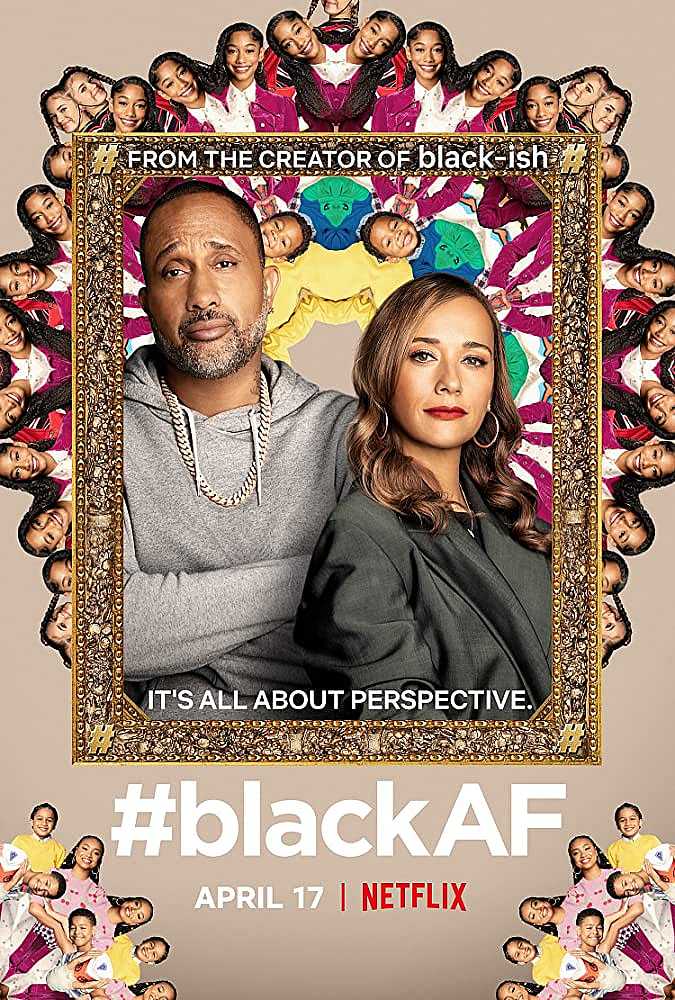

You don’t have to watch beyond the trailer to know that Kenya Barris’ new Netflix show #BlackAF is a reboot of his ABC show black-ish.

Formerly titled #BlackExcellence, black-ish-er is a mockumentary-style series which follows Barris, who plays himself, and a fictionalized version of his family as they deal with various new-money Black people problems.

In December 2019, when Netflix debuted the #BlackExcellence title paired with the cast photo of light-skinned Black people with loose-curl hair patterns — just like the casts of his black–ish, mixed-ish and grown-ish series — Barris was dragged to hell on Twitter. In since-deleted tweets, he defended his hyperfocus on the plight of mixed-race Black people and derided discussions of colorism as “divisive.”

READ MORE: Kenya Barris on facing his fears with Netflix series #blackAF: ‘It was terrifying’

“I really appreciate ur comments & I hardly ever react to social media but this cut me a little,” Barris tweeted of the backlash. “These kids look like my kids. My very Black REAL kids & they face discrimination every [d]ay from others outside our culture and I don’t want them to also see it from US.”

He later changed the show’s name to #BlackAF, which could be seen as a doubling down rather than an engagement with the critique that his multiple shows consistently exclude versions of Blackness that don’t conform to the typical paperbag Hollywood aesthetic for Black people — Black women and girls in particular.

Instead, Barris is knocking down a straw man: that mixed Black people’s Blackness is being questioned. In fact, the consistent critique of Barris’ work is that there is more to Blackness than the struggles of Black people whose mixed-race heritage is apparent, and there is way more to Black storytelling than explaining that version of Blackness to white people.

Which begs the question, who is #BlackAF for? To whom is Barris trying to prove Blackness? And when half the writers’ room is made up of white people, what does “Black AF” even mean?

The series provides conflicting answers to the first two questions, and despite several scenes showing white writers in a writers’ room of the character Kenya’s Black show, the implications of that are never addressed.

But episode five — a microcosm of the entire series — attempts to at least answer what is, for Barris, the ultimate question: what does it mean to be Black?

READ MORE: ‘Insecure’ recap: Issa and Condola’s ‘Sisters Before Misters’ energy

Written by one of the show’s EP’s, Hale Rothstein, the episode follows Kenya, his wife Joya (Rashida Jones) and daughter Drea as they screen a new movie by a Black filmmaker. Kenya and Drea hate it, but everyone else seems to enjoy it. Kenya is asked to moderate a Q&A with the director of the film and he wrestles the entire episode with whether he should do it.

Does being Black in Hollywood mean “rooting for everybody Black,” despite the content, quality and impact of the things they produce? Or does it mean telling Black content creators the truth in order for their work to progress and Black people to progress as a whole?

To answer these questions, Kenya enlists the help of his extended Black family members. He doesn’t usually see his extended family, but Joya forces Kenya to invite them over for a barbecue once she discovers that the Barris kids don’t identify as Black, don’t shoot their NERF guns sideways like in Boyz N the Hood, and, worst of all to Joya, can’t dance.

Because that’s “Blackness.”

This telling B plot continues with Kenya hiding all of his valuables before his extended family arrives. When Joya asks him why he’s hidden laptops in the dryer, he responds with disgust, “You are so mixed.” “Real” Black people know why he needs to take his valuable paintings off the wall when other Black people come over, I guess.

The tropes continue when the family arrives, featuring the drunken auntie (Kym Whitley) and the ex-gang-banger cousin (Melvin Gregg).

“If you haven’t gotten it by now, my dad doesn’t love being around his family,” Drea narrates, and one can’t help but wonder if the family is a stand-in for Black people as a whole.

When the Black family also loves the movie that Kenya hates, he moves on to the opinions of his writers’ room staff. The sole Black woman in the room voices her concerns about letting the white writers, who make up half the room (just like on the real #BlackAF staff), share their opinions on the Black movie.

Kenya — who states the obvious, that he’s “obsessed with the white gaze” — ignores the Black woman’s plea and continues to indulge the white writers as they shit-talk the film. Kenya concludes that white critics are too afraid to honestly critique Black art, and therefore, Black art suffers.

Black critics don’t seem to exist in this world, or, if they do, they’re ignored by Kenya, much like the Black woman in his writers’ room.

To overcome his obsession with white approval, Kenya goes to the man with no writers’ room whom he believes has mastered the art of ignoring white critics: Tyler Perry. Playing himself, Perry gives Kenya advice on “super-serving” his niche Black audience and blocking out the trappings of white Hollywood approval. Perry, whose work has also been heavily criticized by Black critics for years, also has nothing to say about Black critique.

In the most worthwhile scene of the entire series, Kenya assembles what he hopes to be a Black High Council of creatives on a video conference call. His goal is to open up honest communication with other successful Black creatives so that they can all produce better work. After hearing the mildest critique of black-ish, however, Kenya goes into full-on attack mode and the others on the call fire back. The conversation quickly devolves into insults.

The point seems to be that successful Black creatives don’t feel comfortable critiquing their friends, even in private, fearing damage to relationships and career opportunities. Even Drea bleeps out the name of the fictional Black filmmaker they’re criticizing in the episode because she “hopes to work in the industry one day.”

As Barris erases the role Black critics and journalists play in promoting growth and keeping Black Hollywood accountable, he’s accidentally describing our plight.

Black journalists already have to fight to get access to Black entertainers — especially those with gatekeeping white publicists. It’s not hard to imagine that access becoming more limited or cut off altogether if a Black critic produces a less-than-glowing review. The only acceptable version of “rooting for everybody Black,” for some in this industry, is unadulterated praise.

READ MORE: Netflix unveils ‘Hollywood’ trailer starring Laura Harrier

As Black journalists get laid off and Black publications fold — pre-Corona, let alone now —the far more interesting conversation this episode could have explored is how important it is to protect and support Black critics and Black critique as a profession.

In answering the question of what it means to be Black in Hollywood, the episode could have explored how Black creatives can better engage with Black critique and each other without the fear of damage to careers that Drea mentions.

Still, Kenya is on to something: What do Black Hollywood creatives owe to each other? What if every Black creative had a trusted group of Black people who love other Black people and are not afraid to tell them the truth? What if that Black High Council were to have read even the synopsis of #BlackExcellence in its early stages? Hopefully someone could have pointed out the colorist casting pattern, at least.

A Black Council could have read these scripts and told Barris that the series lacks a coherent thesis. It could’ve told him that the constant attacks on Joya as a “terrible mother” in every episode come across as petty and mean, considering his recent in-real-life divorce. It could’ve told him that “obsession with the white gaze” is boring if you never do the work to heal from it. It could’ve told him that most of these issues could be better worked out in therapy rather than on screen.

READ MORE: Netflix shows ‘Nailed It’ and ‘#blackAF’ worth binging in April

But one would also have to be receptive to criticism.

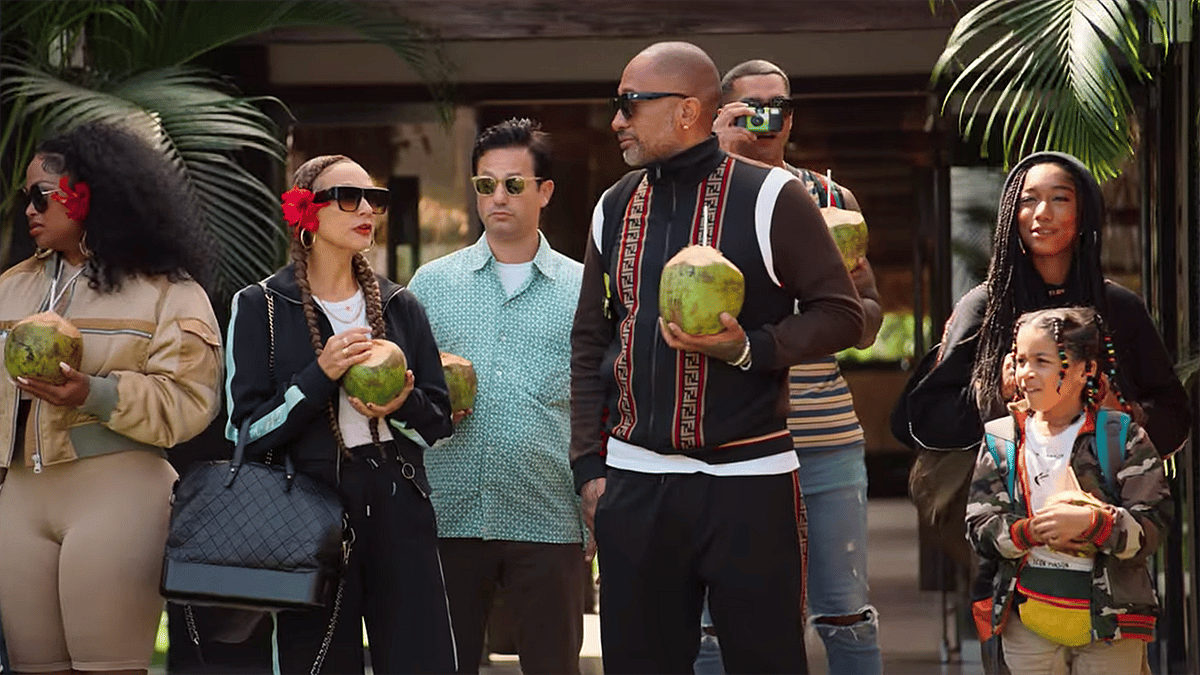

In the series finale, the Barris family goes on vacation to Fiji, where Kenya continues to be awful to Joya. It’s only when he watches an episode of black-ish that he learns the importance of not being a dick to his wife and somewhat changes his behavior. It may be the most incredible example of naval-gazing inception ever filmed.

It seems that the only critique that Kenya can engage with is the one he writes himself.

“Isn’t there a better Black filmmaker that needed their movie to get made but that movie got made [instead]?” Kenya asks his writers’ room. “Am I trash and nobody will tell me?” Kenya asks Joya. “Are we all being trolled?” I ask myself.

But the biggest troll of all might be reserved for Netflix.

After all, each of the episode titles is a variation of “because slavery.” Getting a $100 million Netflix deal to rehash the same tired tropes and ask the same shallow questions for the fourth time, then, might be reparations. So, why not just phone it in? As the #BlackAF theme song proclaims: “Fuck everything else; win, win, win, win.” In that case, congratulations.

Brooke Obie is an award-winning film journalist and author of the Black revolution novel “Book of Addis: Cradled Embers.’