How American racism changed the map of Africa

The U.S. establishment of Liberia is emblematic of the pervasiveness of American anti-Blackness

American anti-Blackness is so pervasive that its impacts have devastated communities at home and abroad. The U.S. establishment of the West African nation of Liberia is a case in point.

From the late 18th to early 19th centuries, the U.S. government was obsessed with what it called “The Negro Problem.” Namely, how to manage the presence of the free population of African Americans, whom it had no desire to integrate into society as equal citizens.

During this period, American leaders wrestled with the contradictions between the ideals of freedom, justice and equality — which drove the American Revolution — and the capitalist and white supremacist ideals that justified slavery and deemed Black people inferior, undesirable and dangerous.

Read More: Africa is slowly peeling apart as new ocean forms, scientists say

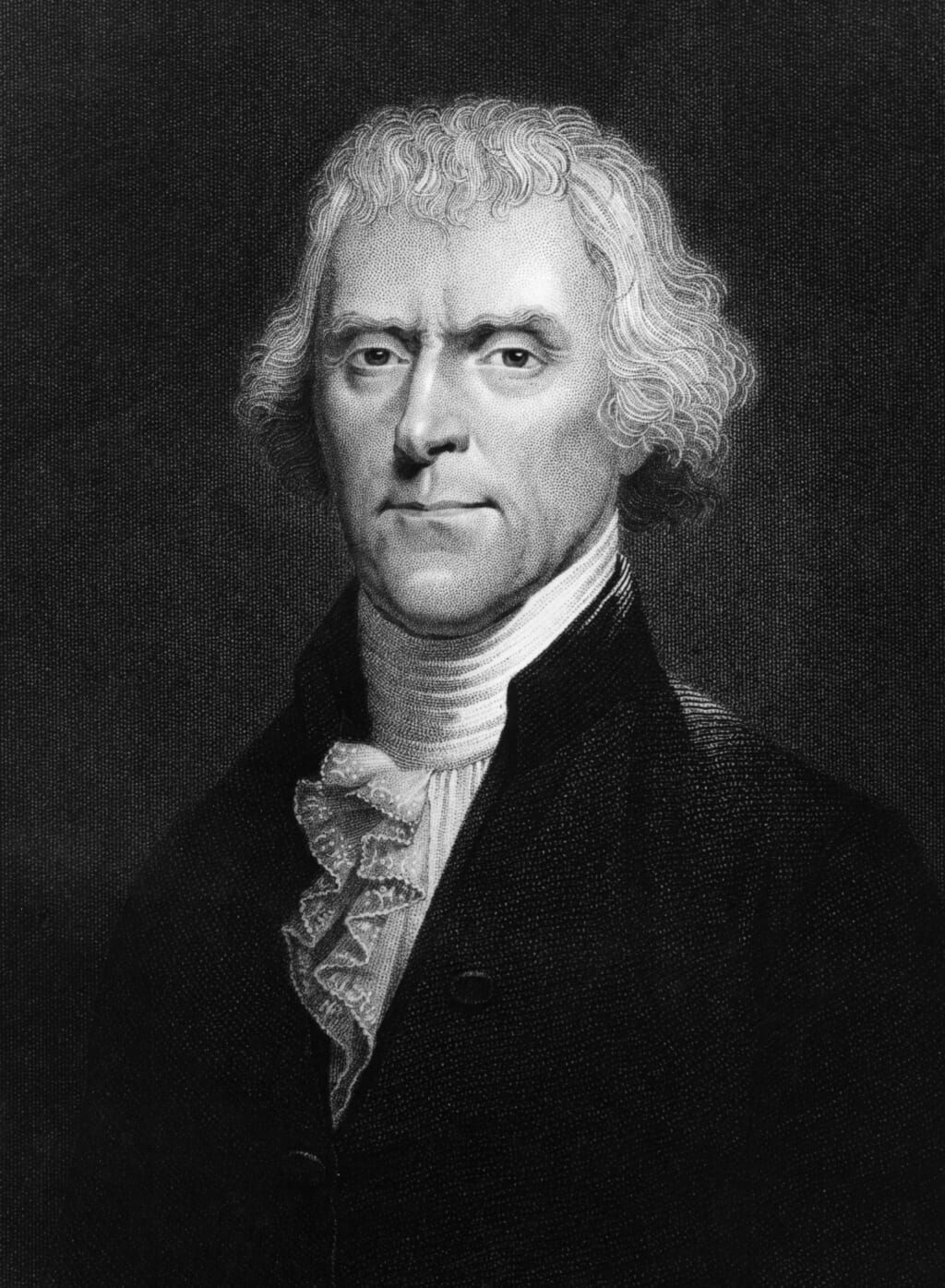

Thomas Jefferson offered a poetic summation of the tensions between slavery and freedom for African Americans when he remarked:

“But as it is, we have the wolf by the ear, and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go. Justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other.”

Jefferson was not alone. His words evoked the fears of many white Americans — slaveholders and non-slaveholders alike. To their minds, free Black people were a threat to the balance of society — as seekers of revenge for mistreatment; as examples of the agency to those enslaved; as competitors for low wage labor with white counterparts; and for the prospect of racial mixing.

The surge of Black resistance to slavery nationally and internationally — heightened these fears. The Haitian revolution (1790-1804) overthrowing France sent shockwaves throughout U.S. slaveholding society — for its potential to inspire widespread rebellion among the enslaved.

Read More: Caribbean nations selling citizenship to Americans due to tourism decline

This potential became reality as a series of revolts took place in the following decades, including Gabriel Prosser’s rebellion in Virginia (1800); the German Coast Uprising in Louisiana (1811); Denmark Vesey’s revolt in South Carolina (1822); and Nat Turner’s insurrection in Virginia (1831).

These turbulent times galvanized support for an idea that Thomas Jefferson expressed in his Notes on the State of Virginia, and again proposed to him by Virginia Governor James Monroe in 1800 following Prosser’s rebellion. Believing that free Black people and whites could never peacefully co-exist in America, the proposal called for the deportation and resettlement of African Americans to a colony in West Africa.

In 1816, a group of prominent white Americans convened to establish the American Colonization Society (ACS) which “hoped to rid the United States of both slavery and black people.” The ACS planned to achieve this by identifying and securing territory in West Africa for the purpose of resettling free African Americans, and those who would become free.

The society was also responsible for garnering political support for the undertaking, and the funding to transport settlers to the new colony, along with the necessary provisions.

The Society’s founders, Virginia politician Charles F. Mercer and Reverend Robert Finley — director of Princeton’s Theological Seminary — had no problem obtaining political support for the endeavor. From the beginning, ACS membership was comprised of leading figures in American society.

These would include Presidents Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, and Lincoln; Secretaries of State Henry Clay and Daniel Webster; Supreme Court Justice Bushrod Washington; and lawyer and poet Francis Scott Key.

Initial financial support for the ACS was provided by President James Monroe, who facilitated a congressional allocation of $100,000 to the Society in 1819. With cash in hand, the Society still struggled to obtain land in West Africa — where the indigenous people in what was then known as the “Pepper Coast” resisted the American resettlement scheme.

In 1821, the U.S. Navy stepped in to coerce local leaders in West Africa to sell a strip of land to the Society. That same year, several dozen free-born Black settlers were brought to the territory, marking the beginning of a violent and contentious relationship between themselves and the indigenous people of the region. It would be established as the independent Republic of Liberia on July 26, 1847.

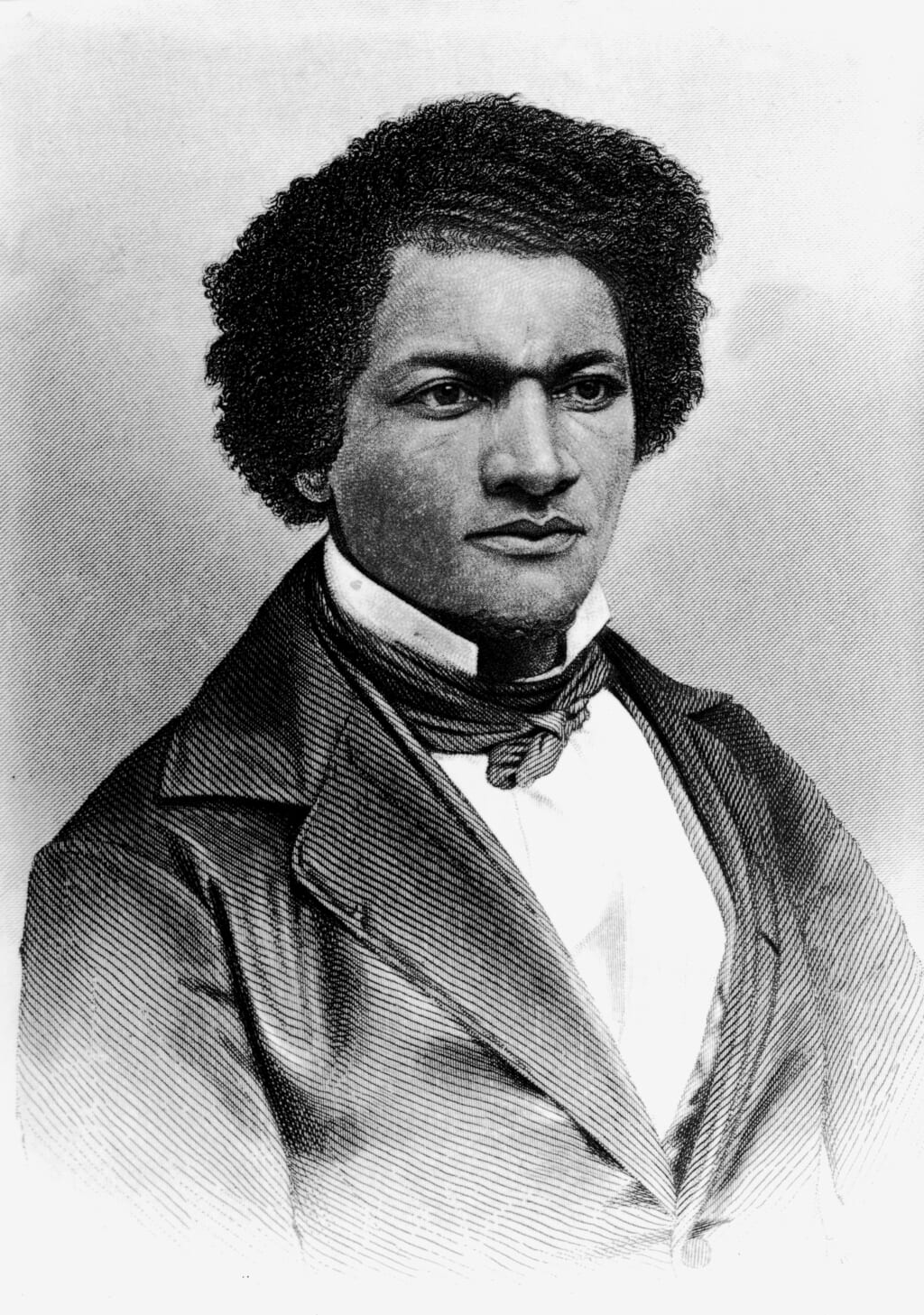

While some African Americans embraced the idea of being sent to Africa, under the belief that Black people would never receive just and equitable treatment in the United States — the majority rejected the idea — claiming the U.S. as the only home they knew. Famed abolitionist Frederick Douglass gave voice to these sentiments when he stated:

Read More: Frederick Douglass statue torn down in New York

“Shame upon the guilty wretches that dare propose, and all that countenance such a proposition. We live here – have lived here – have a right to live here, and mean to live here.”

Colonization was ultimately a failed experiment losing economic and political support domestically — and resettling little more than 13,000 African-Americans in Liberia.

It laid bare the racist ideologies that would stifle the growth of American democracy and exported them to West Africa where the legacy of American racism led to a history of conflict between the settled and the indigenous populations and a history rooted in repression, inequality, and civil war.

Travis L. Adkins is a Lecturer of African and Security Studies at the Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University, a media contributor on issues of social justice and African Affairs, and the host and creator of the On Africa podcast. You can find him at @TravisLAdkins on Twitter.

Have you subscribed to theGrio’s new podcast “Dear Culture”? Download our newest episodes now!