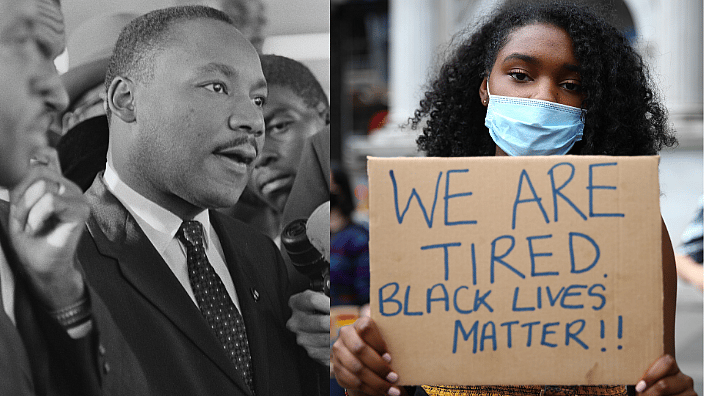

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. — who was assassinated on April 4, 1968, in Memphis, Tennessee while helping striking sanitation workers — left a deep and lasting impact on America through his activism and his advocacy, his philosophy of nonviolent civil disobedience and his radical vision of a just society free from racism, militarism and poverty.

And although we tend to focus on the impact on his life’s work, rarely do we focus on the effect of Dr. King’s death on the community — specifically the ongoing trauma of Black America, and the impact on the movement for Black lives.

Read More: Bernice King maintains father’s assassination was government ‘conspiracy’

Black America mourned King with grief, anger, hopelessness and a range of emotions. His assassination altered the lives and psychology of Black people and arguably continues to impact the community today.

“King’s assassination was an example of a shattering experience that propelled Black people into becoming more politically active and into searching for a deeper understanding of the Black Power movement,” Kevin Cokley wrote in the Dallas Morning News, calling his death the inheritance of current social movements.

“Black people realized that being patient and trusting the country to eventually do right by Black folks was a dream at risk of being permanently deferred. Blacks did not have the luxury of sitting on the sidelines in the pursuit of civil rights. For many, King’s assassination aroused what had been a sometimes muted yet simmering anger fueled by injustice toward Black Americans,” Cokley added.

The death of the civil rights leader sparked the urban rebellions of 1968, although there were other factors at play, such as unemployment, housing segregation and police brutality and harassment — the factors of Black grievance that incited the uprisings across America the year before. Close to 50,000 federal troops occupied American cities in this, the largest unrest of the 1960s, where 39 people were killed and 3,500 were injured.

Further, the loss of Dr. King was a devastating blow to the civil rights movement, raising questions about the effectiveness of nonviolence. On the night of the assassination, Floyd McKissick, director of the Congress of Racial Equality, proclaimed that nonviolence was a “dead philosophy” because white racists killed it.

“When white America killed Dr. King last night, she declared war on us. It would have been better if she had killed Rap Brown … or Stokely Carmichael,” said Black Power activist Stokely Carmichael, later known as Kwame Ture. “But when she killed Dr. King, she lost it … He was the one man in our race who was trying to teach our people to have love, compassion and mercy for white people.”

The Civil Rights Movement and movement for Black lives were both triggered by Black murders, notes Aldon Morris, Leon Forrest Professor of Sociology and African American Studies at Northwestern University and president of the American Sociological Association. Sustained protests resulted from the systemic wounds of Jim Crow segregation, not unlike the present-day devaluation of Black people that gave birth to the Black Lives Matter movement.

Read More: #MLK50: How did Martin Luther King Jr. view death in the face of activism?

“A more pertinent lesson was that overreliance on one or more charismatic leaders made a movement vulnerable to decapitation,” said Morris. “Similar assaults on leaders of social movements and centralized command structures around the world have convinced the organizers of more recent movements, such as the Occupy movement against economic inequality and BLM, to eschew centralized governance structures for loose, decentralized ones.”

Contrary to the present-day whitewashing of King as a dreamer who gave great speeches, King articulated a “fierce urgency of now” that speaks to the rage and frustrations of his time and resonates with our present-day realities.

“Many are now hearing for the first time King’s quote that ‘a riot is the language of the unheard’” said Omid Safi, professor of Islamic Studies at Duke University, who noted King’s position during social unrest was far from moderate. After all, King said “Freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed,” and he expressed his disappointment with white moderates he viewed as more of an impediment to Black progress than the Ku Klux Klan.

Read More: 7 inconvenient truths white people must understand about Martin Luther King Jr.

“The question today is whether the white liberal (and their allies) will overcome their own privilege and listen to the rage of the Black folk who are shouting that they too cannot breathe,” Safi added.

Understanding Black America’s response to King’s assassination requires a grasp of the role of trauma in the Black community. Kidnapped from our homes and sent across the Atlantic in deadly slave-ship dungeons, only to face hundreds of years of torture and enslavement in forced labor camps — followed by Jim Crow segregation and institutional racism — we suffer from intergenerational trauma linked to fatal tragedy.

And the “gruesome public spectacle” of lynchings traumatized Black people. White people brought their children to lynchings with picnic lunches, attended as spectators to a sporting event, and participated in the murders and claimed Black body parts as souvenirs.

This intergenerational curse of trauma has compromised Black health over the centuries. As James Baldwin asked in Go Tell it on the Mountain, “Could a curse come down so many ages? Did it live in time, or in the moment?”

And Black children experience that trauma today, on a variety of levels. “Seeing Black men die on TV — that produces complex trauma. It is interwoven in an interpersonal yet indirect way that gets into your psyche,” said Merland Baker, a mental health counselor licensed in Georgia and Florida.

In addition, the psyches of Black students are damaged when they are rendered invisible academically, yet very visible through police surveillance, says educator and activist Dena Simmons.

“When Black students experience a world that devalues their humanity — including through curricular content that perpetuates narratives of inferiority and excludes their lives and full histories — and when they witness people who look like them being beaten or slain in the media, they are subject to the trauma of being made to feel worthless and unseen, of being made inhuman,” Simmons said.

Experiences with racism range from common yet vague microaggressions to blatant hate crimes and physical violence, says Monica T. Williams, Ph.D. “The unpredictable and anxiety-provoking nature of the events, which may be dismissed by others, can lead to victims feeling as if they are ‘going crazy.’ Chronic fear of these experiences may lead to constant vigilance or even paranoia, which over time may result in traumatization or contribute to PTSD when a more stressful event occurs later.”

Further, it is painfully clear the grief-stricken souls who witnessed George Floyd’s murder by Minneapolis police Officer Derek Chauvin grapple with trauma and survivor’s guilt. In a year marked by collective grief over lives lost to COVID and police violence, the public mourning of individuals such as Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbury and Black Panther actor Chadwick Boseman has unearthed our unaddressed collective Black trauma. At a time when the pandemic of racism remains, are we still mourning Martin Luther King’s death?

The George Floyd protests were wrapped in the COVID-19 pandemic and the racially disproportionate impact on health and economic devastation.

“I think all of that creates a sense of social unease and social unrest, that when you layer on top of the pandemic another, yet another episode of … just cruel violence against an unarmed black man posing no threat, that the two came together and exploded,” said Monica Peek, MD, MPH, an internist at the University of Chicago Medicine who researches health disparities.

From King to Langston Hughes, Black activists have documented the effects of “long-term poverty and hopelessness and disinvestment within the African American community and what that does to the emotional psyche of a people,” Peek added.

Peniel E. Joseph of the University of Texas at Austin believes the King assassination reverberates even today in small and large ways. Just as the 1960s witnessed the long, hot summers of unrest and protest, culminating in the urban rebellions after Dr. King’s murder, people have taken to the streets following the deaths of Black men by police half a century later.

“In many ways our nation is still trying to recover from King’s death and the opportunities for racial equality, economic justice and peace — what King referred to as a ‘beloved community’ — that seemed to recede in its aftermath,” Joseph wrote in The Washington Post, arguing Black Lives Matter — with its intersectional approach linking race, class, gender and sexuality — reflects the radical protest environment of 1968.

“Fifty years after King’s assassination, struggles for racial equality appear as acute now as they did then, except the juxtapositions between signs of racial progress and the reality of continued racial injustice are even more stark,” Joseph said.

The 2020 protests of the murder of George Floyd resulted in the most cities under curfew since the King assassination, and the largest nationwide protest over the murder of a Black man since 1968 — not to mention the largest mass protest in U.S. history with 15 to 26 million participants. Last June, then-Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden insisted the killing of George Floyd had more of a worldwide impact than the assassination of Dr. King. Biden may have a point.

Meanwhile, Black Lives Matter continues the struggles Martin Luther King and the civil rights movement waged to end white supremacy and systemic racism, this time led by Black women. Times have changed, but in many ways, things remain the same. Black America still carried the trauma it experienced when King died, because America still suffers from the pandemic of racial injustice and white supremacy, with no vaccine in sight.

Follow David A. Love on Twitter at @davidalove

Have you subscribed to theGrio’s podcast “Dear Culture”? Download our newest episodes now!

TheGrio is now on Apple TV, Amazon Fire, and Roku. Download theGrio today!