What happened to Robert F. Kennedy Jr., and why isn’t he more like his father? A prominent anti-vaxxer—son of the late former U.S. attorney general, senator and presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy and nephew of slain President John F. Kennedy—RFK Jr. is spreading misinformation about vaccines and exploiting the Black community in the process.

Although anti-vax sentiment in the COVID era—including anti-vax conspiracy theories and snake-oil hustles and miracle cure-alls promoted on social media—is most often associated with rightwing organizations and individuals, Kennedy has established himself as a leader in this dangerous and fraudulent movement. While the Kennedys have maintained a liberal-to-progressive brand name over the years, RFK Jr. shares common cause with such unhinged, extremist and anti-democratic figures as Roger Stone, Michael Flynn and InfoWars’ Alex Jones.

Kennedy has faced much-deserved criticism for his anti-vaccination documentary, Medical Racism: The New Apartheid, which spreads lies about vaccines and targets Black people to make its points—and a lot of money. Particularly sinister is the reality that Black people, who have suffered from a long legacy of medical racism, disproportionately suffer and die from a host of diseases, including COVID-19. The film claims vaccines are harmful to the health of Black people and compares the “dangerous experimental” vaccination of Black people in Haiti, Africa and the U.S. to the infamous Tuskegee syphilis experiment. In Tuskegee, the U.S. government used Black men as guinea pigs, leaving their syphilis infections untreated and allowing them to suffer and die from the disease. Penicillin would have treated those Black people, just as the COVID vaccine is saving Black lives today—a vaccine Kennedy believes Black people should not take.

A wealthy white man and member of a political dynasty, Kennedy uses his family name and civil rights legacy to raise money for his anti-vax nonprofit, Children’s Health Defense. Even as many nonprofits have struggled during the pandemic, CHD is raking in millions of dollars and attracting millions of people to its website. Kennedy, who has a social media presence on Twitter and Facebook, was banned from Instagram for spreading misinformation. And while Kennedy pedals anti-vax conspiracy theories, guests invited to his home for a holiday party were urged to be vaccinated or tested for COVID-19, only bolstering arguments that Kennedy is at best grifting on the backs of Black folks. Kennedy blamed his wife, actress Cheryl Hines, for the pro-vaccination invitation.

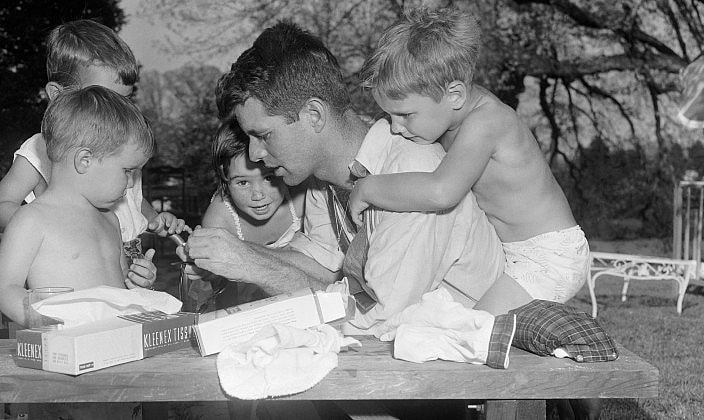

In contrast, Kennedy’s father, Robert F. Kennedy Sr. was adored and revered in the Black community and one of the most beloved white men in Black America. But the senior Kennedy, like many white people, started out clueless about race. Early in his career, he worked for the maniacal Sen. Joseph McCarthy, whose House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) had investigated prominent Black figures such as Lena Horne, Paul Robeson, Ruby Dee, Ossie Davis, Langston Hughes, Richard Wright and others for alleged Communist ties.

The beginning of Kennedy’s transformation came when James Baldwin arranged for him, then the attorney general, to meet with a group of Black artists, civil rights leaders and academics at the Manhattan apartment of Kennedy’s father. In attendance were people such as playwright and writer Lorraine Hansberry; Harry Belafonte; Lena Horne; Clarence Jones, an adviser to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.; psychologist Kenneth Clark, and young Southern freedom activist Jerome Smith, who was in New York to receive medical treatment for the police beatings he had sustained in the South.

Kennedy Sr. touted the administration’s accomplishments on civil rights but warned that they could not alienate conservative Democrats in the next election and asked the group why so many Black people were drawn to the scary Malcolm X and the Black Muslims. He spoke of his own history of oppression as an Irish American and thought the country would elect a Black president within 40 years. Kennedy expected gratitude and Black respectability, but what he got instead was Black rage.

“I’ve seen you guys [from the Justice Department] stand around and take notes while we’re being beaten,” Smith told Kennedy. Smith warned the threat was not from Black Muslims but from people such as himself, whose patience wore and was losing faith in nonviolence. Smith envisioned a need for him to use a weapon against the police and also told Kennedy that Black young people would not go to war for America.

Hansberry told the attorney general they wanted a moral commitment from him and said, “the only man you should be listening to is that man [Jerome Smith] over there.” The author of A Raisin in the Sun also told Kennedy “I am very worried…about the state of the civilization which produced that photograph of the white cop standing on that Negro woman’s neck in Birmingham.”

Baldwin—who had blamed the Kennedy administration for failing to intervene and stop the white violence against Black people in the South—recalled the meeting. “From the point of view of the man in the Harlem barbershop, Bobby Kennedy only got here yesterday, and he’s already on his way to the presidency. We’ve been here for four hundred years, and now he tells us that maybe in forty years if you’re good, we may let you become president,” Baldwin said in his legendary University of Cambridge debate with William F. Buckley in 1965.

The meeting shocked and angered Bobby Kennedy. However, he began to look at race in a different way. He began to care about hunger and poverty, championed the plight of poor Black, white, Latinx and Native American people, opposed the Vietnam War and stood with striking Mexican-American farmworkers in California. In his 1968 presidential campaign, Kennedy managed to forge a coalition of working-class Black and white voters.

In April 1968, at a rally in the heart of the Black community in Indianapolis, Kennedy announced that King was dead. “For those of you who are Black and are tempted to fill with—be filled with hatred and mistrust of the injustice of such an act, against all white people, I would only say that I can also feel in my own heart the same kind of feeling. I had a member of my family killed, but he was killed by a white man,“ Kennedy said, referring to the assassination of his brother and calling for love, wisdom and compassion in America rather than violence and lawlessness. “So I ask you tonight to return home, to say a prayer for the family of Martin Luther King—yeah, it’s true—but more importantly to say a prayer for our own country, which all of us love—a prayer for understanding and that compassion of which I spoke.”

Bobby Kennedy had become the most loved white man in Black America, an heir to the civil rights mantle who sought racial healing, and one of those few white leaders who spoke out for Black, Brown and poor people. Only a few months after Dr. King was assassinated, Bobby Kennedy was shot to death.

“But suppose God is Black? What if we go to Heaven and we, all our lives, have treated the Negro as an inferior, and God is there, and we look up, and He is not white? What then is our response?” Bobby Kennedy once said.

This is why old-school Black households have portraits of Martin Luther King, John F. Kennedy and Bobby Kennedy hanging on their wall. And this is why Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is nothing like his father. The father wanted to bring people together, while the son exploits Black people through racism and disinformation in the age of Trump.

David A. Love is a journalist and commentator who writes investigative stories and op-eds on a variety of issues, including politics, social justice, human rights, race, criminal justice and inequality. Love is also an adjunct instructor at the Rutgers School of Communication and Information, where he trains students in a social justice journalism lab. In addition to his journalism career, Love has worked as an advocate and leader in the nonprofit sector, served as a legislative aide, and as a law clerk to two federal judges. He holds a B.A. in East Asian Studies from Harvard University, and a J.D. from the University of Pennsylvania Law School. He also completed the Joint Programme in International Human Rights Law at the University of Oxford. His portfolio website is davidalove.com.

Have you subscribed to theGrio podcasts “Dear Culture” or “Acting Up?” Download our newest episodes now!

TheGrio is now on Apple TV, Amazon Fire and Roku. Download theGrio.com today!