Editor’s note: The following article is an op-ed, and the views expressed are the author’s own. Read more opinions on theGrio.

As the Emmett Till Antilynching bill moves toward becoming law, I want to remember some of the people who were critical to ensuring that Till’s death wasn’t forgotten. Thousands of people were brutally murdered by white mobs, and some stories are more gruesome than Till’s tragic end. But most of their names are lost to history, while Till’s story has affected millions because of the people who made sure the world knew what happened.

Four days before she got on the bus that would make her a hero, Rosa Parks went to a packed meeting at a local Baptist church where they heard about the trial of Emmett Till’s killers and their speedy acquittal—the jury deliberated for about an hour. What Parks heard about the case shook her to her core. Days later, on the bus, when she was ordered to give her seat to a white person, she refused but not because she was physically tired. It was because of Till. “I thought of Emmett Till,” Parks said, “and when the bus driver ordered me to move to the back, I just couldn’t move.”

Parks knew that there had been others like Till. The custom, she said, was, “to keep such things covered up…There were several cases of people that I knew personal who met the end of their lives in this manner and other manners of brutality without even a ripple being made publicly by it.”

Parks could not stand by even one more time.

The reason why Parks knew who Till was is because of his mother, Mamie Till. When she got her son’s mutilated body back from the state of Mississippi, his coffin was locked. People had signed papers agreeing to keep it closed, but Mamie Till demanded the undertaker open it. When she saw what Till’s murderers had done, she said, “Let the world see what I’ve seen.”

She refused to let a mortician touch up the body, and she ordered the casket be open. The body lay in the church for four days as tens of thousands of people paid their respects. She wanted the world to know what had happened. I cannot imagine the pain she felt. I cannot imagine the anger she felt. I cannot imagine leaving a coffin open when my baby’s body has been mutilated by racists. But Till stood up to them by letting the world see exactly what happened. It was her courage, strength, anger, defiance, resolve, and power that made all the difference—that and her reaching out to Black media.

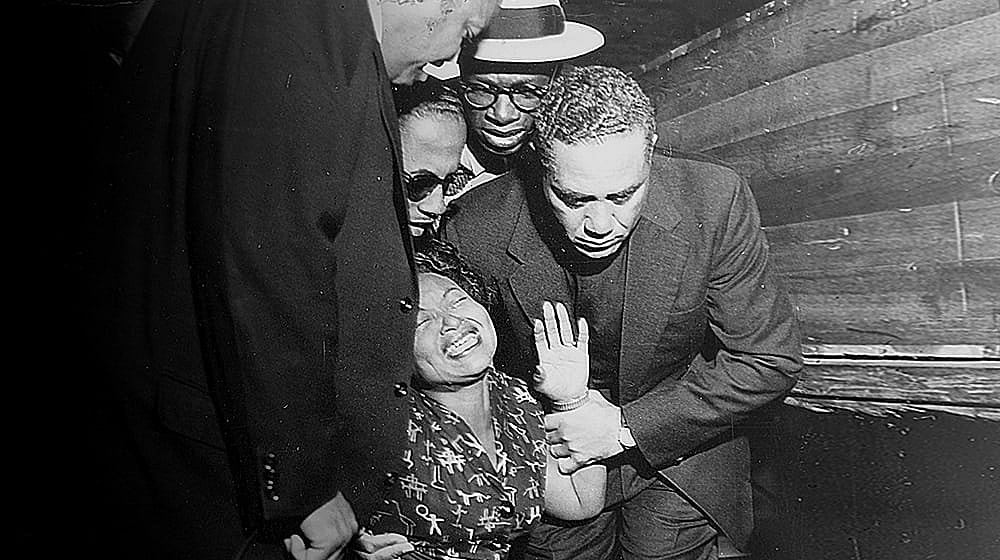

Till called several Black media publications and implored them to come and take pictures. Back then, Jet magazine was in almost every Black household—both of my grandmothers were loyal subscribers. Jet photographer David Jackson took the famous image of Till in the coffin as Mamie Till cried out, “Darling, you have not died in vain! Your life has been sacrificed for something!”

At the time, no white media organization printed the image of Till. Americans were usually spared from seeing potentially traumatizing images of violence—decency called for looking away out of respect and a desire to maintain decorum—but over at Jet, Jackson’s editors recognized what Mamie Till saw. This was violence that had to be seen. The only way to show respect to Emmett Till was to see what was done to his body. The gruesome image ran in Jet and seeing it changed people. It shook them. It added a new sense of imperative to the civil rights movement. This is why it’s critical to have Black-focused media organizations—they will make choices that white organizations won’t, choices rooted in the notion that Black lives matter.

I do not believe in the notion that everything happens for a reason. I think humans are good at finding reasons for everything, especially if you apply a long enough timeline. But if you believe in that notion, then perhaps you can say Emmett Till did not die in vain; perhaps you can even look at Till as a Jesus-like figure in that he’s someone who was crucified by the powerful so that millions of oppressed folks could live a better life. But Till’s life would not have had a galvanizing, historic impact without an unflinching photographer and his steely mother who insisted that the world see reality.

Touré is the host of the podcast “Toure Show” and the podcast docuseries “Who Was Prince?” He is also the author of seven books.

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku, and Android TV. Please download theGrio mobile apps today!