Bad air kills Black people.

That’s what the federal government says. Black people, far more than their white counterparts, live not only in poorer and noisier conditions, but with higher levels of pollution, leading to a host of maladies and death. Worse, deliberate federal racist policies — a history of practices the United States acknowledges —go unchecked by Congress that allows the lethal circumstances.

These pollutants, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, lead to health problems that include heart and lung disease. And that’s not all. Researchers believe there’s a link between air pollution and type 2 diabetes — a disease that half of Black people stand a chance of developing.

Black people choking on filthy air know all of that. So do the officials who created the conditions. There’s research that shows it – yet, there’s still Africatown.

Historic Africatown, home to the last known slave ship to sail to America, sits along Mobile, Alabama’s African American Heritage Trail and has been named a world preservation site by the World Monuments Fund.

Africatown has another distinction: A sickening smell.

“The air stinks awful,” said Ramsey Sprague, president of the Mobile Environmental Justice Action Coalition,

Africatown, sadly, mirrors too many Black communities across the country. Whether it’s zip codes in St. Louis, Detroit, or tiny enclaves like Piney Woods, Mississippi, a legacy of systemic racism has resulted in Black people breathing air far dirtier than any other demographic group.

The Environmental Protection Agency has ramped up its environmental justice efforts but its impact is limited by Congress. The EPA can enforce regulations and penalties and strengthen oversight. But it can’t make laws designed to reduce emissions in poor, Black neighborhoods, improve the air, and make breathing easier.

Congress, so far, has not acted in any meaningful way.

Consequently, there’s a countrywide, grassroots movement to rally support and raise awareness on how traffic jams and factories can impact the health of a community’s disenfranchised residents. These organizations, like the Mobile action coalition, South Bronx Unite, and the Climate Reality Project, push for change in clean air and water regulations that local, state, and federal governments have been slow to strengthen.

“What passes as environmental justice policy is not much more than declarations of good intentions,” said Paul Mohai, one of the country’s leading environmental justice experts and a professor at the University of Michigan.

“Decades of bad discriminatory policy decisions … “

Many observers point to a 1982 Warren County, North Carolina, protest over a proposed landfill as the start of the environmental justice movement. But the decisions that led to the movement started decades before and link back to racist policies that continue to affect Black and brown people.

“The disparity in terms of who is being hit first and worst by our growing environmental and climate crisis (is) not just happenstance, right?” William J. Barber III, director of environmental and climate justice for the Climate Reality Project, said. “These are all manifestations of decades of bad discriminatory policy decisions.”

Former Vice President Al Gore, in 2005, founded the Alliance for Climate Protection, which later became the Climate Reality Project. which Barber helps spearhead climate justice efforts. The nonprofit group, based in Washington, D.C., seeks to bring awareness to climate challenges across the globe by focusing on three main areas — build support for addressing climate change, transition to a clean energy economy and reduce emissions.

Unlike most of the community-based efforts, Climate Reality has a big-name founder and chairman (the former vice president), which gives it immediate gravitas. Its $20 million-plus annual budget, from grants and contributions, allows it to maintain a worldwide network of activists to help meet its objectives.

Among a number of environmental issues, the group focuses on bad air that traces back to the government’s redlining policies of the 1930s. Richard Rothstein’s book, The Color of Law, recounts how government-backed policies kept America segregated. Rothstein is also a senior fellow (emeritus) at the Thurgood Marshall Institute of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.

The Federal Housing Administration refused to back mortgages in Black areas and neighborhoods near Black communities. Its Underwriting Manual explicitly said so.

This is true because of the opposite effects produced on the economic life estimate and on the Location rating by threatening or possible encroachments of nonconforming land uses and by threatening or possible infiltration of inharmonious racial groups. The possibility or imminence of such encroachments or infiltrations will always result in low ratings of some of the features in the Location category. – FHA Underwriting Manual, 1936

Nonconforming land use, simply put, means structures that were fine under original zoning laws but wouldn’t be acceptable under updated rules.

Lenders color-coded neighborhoods to indicate those that were good and bad mortgage risks. Black areas were designated red, hence the term redlining. Redlining made it easier for factories to open in “undesirable” areas with cheap land serving as a lure to polluting businesses. A study published in the journal Environmental Science & Technology Letters draws a direct line between redlining and higher levels of air pollution.

Fast-forward to 1956, when the Federal Aid Highway Act passed so that America could build 41,000 miles of interstate highways. Government planners, often purposely, designed highways to go through Black neighborhoods, tearing down churches and homes and upending businesses.

“The highways tore through once-vibrant communities, ripping the social fabric and inflicting psychological wounds on those who were forced to leave their homes and those who were left behind,´ Deborah N. Archer, a New York University law professor, wrote in her article “White Men’s Roads Through Black Men’s Homes: Advancing Racial Equity Through Highway Reconstruction.”

The highways brought more polluting trucks and heavy vehicles through, or near, Black neighborhoods, filling the air with exhaust fumes.

Now, 86 years removed from the government’s official redlining policy, new studies show how racism of the past is still making Black people sick.

“Highways are a significant source of air pollution, with communities of color,” said Barber, a longtime community organizer and son of the Rev. William Barber II, a social justice activist who is co-chair of the Poor People’s Campaign. “The same communities that were redlined are being disproportionately exposed to air pollution from your trucks, from your cars, from the general traffic.”

One 2019 study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, looked at the effects of the “pollution burden,” defined as “the potential exposures to pollutants and the adverse environmental conditions caused by pollution.” The study said Black people’s pollution exposure is 56% greater than that of whites. It’s even worse for Latinos – 63%.

Simply put, it means people of color breathe much dirtier air.

That has health consequences. Black adults are twice as likely to develop type 2 diabetes, which can lead to kidney and heart disease and death. The EPA says there’s a link between air pollution and diabetes.

Air pollution also could contribute to higher levels of asthma in some children of color, according to the National Center of Biotechnology Information. About 26 million Americans, including 7 million children, suffer from asthma. The CDC also notes that the prevalence of asthma among Black children is nearly twice that of whites.

“Poor communities and communities of color don’t simply choose to live in areas that are exposed to more pollution, and they don’t simply just choose to stay,” Barber said. “It’s been bad policy decisions, often rooted in structural racism, political exploitation, and economic exclusion that have put entire communities into highly impacted, highly exposed locations for generations. And when we see it, you know this.”

“It sucks.”

When Bronx resident Daniel Chervoni wants to breathe well, he goes to his garden.

There, surrounded by a few trees in a densely populated and poor neighborhood, Chervoni can at least get a few hints of fresh air. Otherwise, he said of the pollution, “It sucks.”

“I’m an asthmatic,” Chervoni said. “I have COPD. I have bad lungs. When I caught COVID in February of last year I was hospitalized for three months. When the pollution is bad, my lungs get tighter, and I have to use my albuterol pump more often. I have to find a place where there’s not too many vehicles going by.”

But the Brook Park Community Garden sits in the Mott Haven section in the South Bronx, New York. The Bronx – the third most densely populated county in the country – has some of the highest incidences of asthma in the United States. The asthma hospitalization rate eclipses the national average by 21 percent, and residents there are more than three times more likely to die of asthma than other New York State residents.

That’s why residents – nearly all Black, Latino and poor – dubbed Mott Haven Asthma Alley.

“Can it be any clearer there’s an injustice taking place in itself? That’s what we’re saying,” resident Mychal Johnson said.

Johnson is a founding member of South Bronx Unite, a nonprofit group that focuses on environmental, economic and social justice issues in the area. Over the years, the group has fought against the relocation of an online grocery-delivery company, Fresh Direct, from the borough of Queens to the South Bronx.

The group’s work examining the noise, pollution and traffic congestion caused by large warehouses has been published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.

They do all of this, and more, with three paid staff and a five-member board who tirelessly advocate for their community.

Johnson walked through all the environmental burdens that Mott Haven has had to endure over the years. The area contains four natural gas power plants and nine waste transfer stations. Some 1,000 trucks from a 400,000-square-foot Fresh Direct warehouse that opened in 2018 increased traffic flow, by as much as 40 percent, and black carbon air pollution. FedEx has a shipping center in the area, too.

Even worse, Mott Haven sits less than three miles from Hunts Point, home to the Hunts Point Market, which sends as many as 16,000 truck trips a day through the city. The nearest highway, the Bruckner Expressway, essentially splits Hunts Point from Mott Haven.

Fresh Direct and FedEx Ship Center can be seen at the bottom left.

Mott Haven’s story illustrates William Barber’s remarks that polluting factories operate in poor neighborhoods split by highways that bring in more traffic and pollution.

But Johnson notes something that’s disturbing: Residents have gotten used to the stench.

“You don’t smell it when you’re here all the time, but when you leave and you come back, you smell it,” Johnson said. “Come into the neighborhood and you get a whiff of – something unpleasant. “It’s distinctive.”

The odor gets worse in the summer because the trash from the waste plants begins to fester in the New York heat. That brings a fly infestation, Johnson said.

“The everyday occurrence of that smell goes without notice because they’re normalized, just like the noise,” Johnson said.

“Not as concerned about the environment…”

(Source: Dave Brenner at the University of Michigan School for Environment and Sustainability)

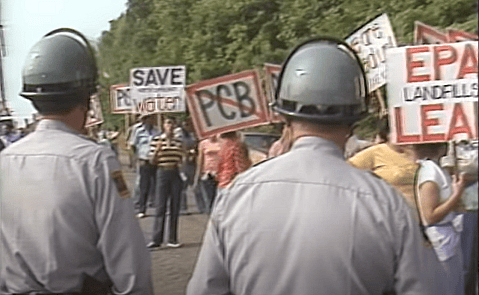

In 1982, the state of North Carolina needed a place to put PCB-contaminated soil that had been illegally dumped along the roadways. The state selected Warren County – a small and mostly Black community – for the toxic waste landfill and people were upset.

The NAACP coordinated a massive protest in which 500 people were arrested. And while the protest didn’t stop the landfill, it started a movement that surprised a number of people.

“I think there’s still some segments of our society that believe African Americans and other people of color are not as concerned about the environment as their white counterparts, that jobs and economic growth are (a) higher priority,” Mohai, an environmental justice professor at the University of Michigan, said.

“And so I think this is one thing that kind of surprised the dominant culture, if you will, back then, that here you had an African American community very concerned about the environmental impacts of this waste landfill and were willing to go to lengths.”

In the years since, evidence of the disregard for Black health mounted.

In 1983, the study “Solid Waste Sites and the Houston Black Community” showed Houston leaders targeted Black communities to house garbage dumps.

In 1987, the United Church of Christ released Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States, a groundbreaking study that used data to show the disproportionate effects pollution had on communities of color.

In 1990, Mohai and Bunyan Bryant organized the Michigan Conference on Race and the Incidence of Environmental Hazards at the University of Michigan. The event was one of two credited with surfacing environmental justice as a concern of the EPA.

Bryant is renowned as a pioneer for his environmental justice work. He was the first African American member of the School of Natural Resources and Environment faculty at the University of Michigan, which is where he and Mohai met.

During the next several years after that conference, study after study noted pollution’s disproportionate impact on Black people and communities of color.

The thread that runs through all of the initiatives, conferences, and research indicates lots of action by community groups desperate for change but little action on the state and federal levels.

Mohai called President Bill Clinton’s 1994 executive order that mandated the EPA to implement environmental justice policies the “high-water mark on environmental justice policy in the U.S. for a very long time. There’s never been any national legislation on environmental justice that’s passed. But like I said, there are bills introduced in Congress, and there have been hearings but no, nothing is ever passed,” said Mohai, who has been involved in environmental justice issues for more than 30 years.

Mychal Johnson of South Bronx Unite said he believes he knows why nothing ever seems to happen.

“You have … polluting industries paying lobbyists very handsomely to keep legislation from being too burdensome for them,” Johnson said. “The industry is supposed to provide services to the public, but you’re hurting the public with the industry. The evidence is clear, the science is clear, that we have to do something different.”

But the question is, what?

“The biggest disappointment, really, is not having any national legislation on this issue, not having… policies that have any teeth in them,” said Mohai, who testified before the U.S. House in 1993 and 1999 and the Senate in 2007.

“Sure, the federal government has all sorts of agencies and will point to their environmental justice policies,” he said. “A lot of state governments will also point to what they’re doing. But nobody’s shown any evidence that any of that has made any difference on the ground.”

“The odor was horrendous.”

Ruth Ballard remembers Africatown before it was Africatown, back when the poor Mobile-area community was called the Plateau.

She grew up there in the shadows of the International Paper Co., Bemis Bag Meal, and the Scott Paper Co.

She remembered neighbors would sometimes have to rewash clothes because the emissions from nearby smokestacks covered them in brown and white specs. She said both paper companies had car washes available so anyone, employees and community members alike, could wash their cars day or night.

“It was just very difficult at that time growing up in the area. We did not know the implications of what was going on at that time,” she said.

And the stench?

“The odor was horrendous.”

Bemis Bag Meal closed in 1972 and International Paper in 2020. The Kimberly-Clark Corp. bought Scott in 1995. The company still operates in Mobile.

The companies may be gone or in different hands, but the scars remain.

Ballard said five of her siblings have cancer and three died. She said she’s beat cancer twice, as has a surviving brother. She has another sister who died of heart disease. “I did research and could not find any linkage where there were cancer genes in our family,” Ballard said.

Some 32 West Africans, the descendants of slaves, founded the town in 1872. They had been smuggled over in 1860 on the Clotilda, a boat burned and sunk to hide the criminal activity. In 2018, researchers recovered a portion of the ship, which will be part of an Africatown museum scheduled to open in May 2022.

Africatown should be known for that history. Instead, it’s known for a history of racism that led to crippling pollution.

In Africatown, “There’s a number of refineries. There’s paper mills. There’s existing sites that are rigorous reporting sites,” Ramsey Sprague of the action coalition said.

“There are lumber companies, lumber treatment companies. There’s a lot of warehousing,” he said. “There’s two interstate highways, two state highways and four major rail lines that all go through what is known as Africatown.”

Sprague, Ballard and others have been fighting for better air quality for years. The action coalition and other local groups, in February, asked Mobile city officials to strengthen zoning laws to keep heavy industry out of or near Africatown. Those efforts are still ongoing, Prague said.

Founded in 2013, the action coalition, with its partner organizations, keeps residents in Africatown and beyond informed on clean air, water, soil and other issues.

The coalition focuses on zoning issues, including rezoning applications and strengthening zoning protections for future development in Africatown. The group challenges state environmental authorities who the group says don’t always perform environmental justice reviews of permitted projects.

They do all of this with a group of volunteers and no paid staff. If that wasn’t enough, Sprague said Africatown faces a different problem – no research to back up what its residents report.

“There’s a dearth of published academic research to deal with what is, anecdotally, common in households in these areas,” Sprague said. “Where cancer is rife. Where there’s kidney disease, heart disease, hypertension, neurological disorders and a lot of respiratory distress. A variety of asthma, COPD, etc.”

He said the action coalition’s surveys show the extent of the health issues, but those findings “are not reflected in any public health initiatives by any local public health agency whatsoever.”

The Grio reached out to the Alabama Department of Public Health and the Alabama Department of Environmental Management. Neither responded.

That lack of data frustrates Ballard. “That’s my belief, that it was the environment that I grew up in that caused my health issues,” Ballard said.

The EPA does report a lot of top-line data, but it’s complicated to use. The EPA offers a environmental justice and screening tool. Use the menu bars at the top left to enter an address and generate a report about pollutants. The EPA also offers a search by zip code option that shows any number of pollution sources. It produces a map that looks like this:

The map shows the 36601 zip code. The red indicates the area sits in the 95 to 100 percentile for particulate matter 2.5, the tiny particles that can cause a myriad of health problems, including premature death for those with heart and lung issues. (The Grio, in researching zip codes on the EPA site, experienced intermittent issues with maps not showing information).

But the EPA, like any federal agency, is limited in its scope. To its credit, the EPA, under new administrator Michael S. Regan, has shown it’s paying attention to environmental justice issues. Regan, the first Black man to lead the EPA, went on a listening tour through Louisiana, Mississippi and Texas to highlight environmental justice concerns in marginalized neighborhoods.

Following that tour, he announced the EPA would take a number of steps, including investing in community air monitoring, holding companies accountable with increased oversight, and “aggressively” conducting unannounced inspections.

Despite its best efforts, any substantive change must come through ordinance or legislation. There simply hasn’t been anything meaningful.

“Enough of this”

The White House has already pledged efforts to help Black communities that are suffering from environmental injustice, but with a catch. They’re making the system race neutral in hopes it would survive any potential court actions claiming the program shows preferential treatment and holds biases against whites.

Looking at the zip codes most affected by pollution, though, shows the vast majority are in poor communities dotted with Black and brown faces. They are communities with small, underfunded groups trying to reverse decades of systemic racist practices on the environment that are, at best, making communities sick and at worst, killing people.

These are the communities in which Daniel Chervoni struggles to breathe; where Ruth Ballard wonders if industrial pollution caused her cancer; where Ramsey Sprague, William Barber, and Mychal Johnson see every cough, wheeze and death as a reminder of a past that environmentally targeted people who look like them.

“The land is cheap,” Johnson said, “and because low-income people of color don’t get proper representation, the cycle continues. Enough of this. Our children are suffering.”

ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE GROUPS AND AIR QUALITY

Here are a few organizations that fight for environmental justice as well as tools to use to see the air quality in your zip code.

You can measure air quality by zip code at Airnow.gov.

For the Planet has a lengthy list of environmental justice groups around the country.

The World Air Quality Index has an easy-to-use map that provides real-time air quality information.

ProPublica, the nonprofit journalism site, has an easy-to-use map that shows cancer-causing industrial air.

You can reach the organizations mentioned in this story at the Mobile Environmental Justice Action Coalition. South Bronx Unite, and The Climate Reality Project.

The EPA has an environmental justice timeline that looks at some of the watershed moments since 1968. Among them: the Memphis sanitation workers’ strike, the Warren County, North Carolina, protests; and the Flint, Michigan, water crisis.

TheGrio is now on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku, and Android TV. Also, please download theGrio mobile apps today!