Editor’s note: The following article is an op-ed, and the views expressed are the author’s own. Read more opinions on theGrio.

As monkeypox cases rise and growing concerns permeate the airwaves, it’s time to address the impact this virus is having on gay and bisexual men. New York City has already reported 639 cases as of July 19, with nearly all of them involving men who have sex with men, according to the city’s Department of Health. With many more cases likely undiagnosed as a result of systemic barriers to healthcare services combined with a vaccine shortage to combat the outbreak, it’s likely that this upsurge will get worse before it gets better.

New York City’s health department is one of many public health organizations that is struggling with its messaging. Monkeypox is ubiquitous in nature—it doesn’t care if you are white, black, yellow, or green; and it’s capable of infecting both men and women—but thus far men who have sex with men, particularly those with higher numbers of reported sexual partners, have been hit the hardest. The public health community is struggling to figure out why—thus far there is no evidence that points to monkeypox being a sexually transmitted disease—while also being careful not to label this viral outbreak as a “gay disease.”

The wounds of poor messaging during the HIV/AIDS epidemic are fresh and there’s a great need to gather more information and protect our most vulnerable populations from stigma, but let’s not ignore who is suffering the most. While everyone may be at risk, as is always the case with any infectious disease, the focus of public health efforts must be on unpacking the nuances that are contributing to this puzzling imbalance.

What is Monkeypox?

Monkeypox is a rare pox virus (the same family of the more well-known smallpox and cowpox viruses) that is transmitted from animals to humans. It was first identified in Africa, but its true country of origin is unknown. The virus causes an initial flu-like illness that is followed by a rash. It is spread primarily through skin-to-skin contact, especially when someone touches an infected sore. Less commonly, it can be spread through respiratory droplets (aerosols) in the air and contaminated surfaces (fomites) so the same COVID-19 precautions—mask wearing, isolation, handwashing, and prompt testing and treatment—should be enacted if there is any suspicion of monkeypox exposure.

Symptoms

According to the CDC, monkeypox begins with a constellation of symptoms that includes fever, headache, muscle aches, and fatigue. Some people experience all these symptoms while others experience one or none at all. Next, patients develop swollen lymph nodes followed by a localized rash that usually starts on the face and spreads to other parts of the body.

Despite the pictures of monkeypox welt-like rashes that have dominated the internet, monkeypox rashes are non-specific and may easily be confused with rashes that develop from other medical conditions. The typical monkeypox lesion progresses through four stages— macular, papular, vesicular, to pustular—that is, they begin as flat spots that quickly transform into raised pus-filled bumps. Eventually, these blisters resolve, crusting over and turning into scabs that fall off in two to four weeks.

Diagnosis

Monkeypox is a clinical diagnosis made in the presence of fever, lymphadenopathy, and rash that is not explained by other causes. The diagnosis is confirmed by PCR testing of a scraping from an open lesion that detects the presence of the virus.

How it spreads

Monkeypox is most commonly transmitted through skin-to-skin contact with open lesions and less so with contact with respiratory aerosols (small droplets that linger in the air after coughing or sneezing). It can also be spread through body fluids and contaminated surfaces (fomites) like kitchen countertops and bedding. Vertical transmission, which is transferring the disease from mother to infant during pregnancy, has been documented.

Monkeypox is not a sexually transmitted infection, although any close skin-to-skin contact with someone who is contagious with monkeypox can put you at higher risk of contracting the disease.

Who’s at risk?

Anyone who is in contact with someone who is infected with monkeypox is at risk of contracting the disease, regardless of how long you spent with the person. While monkeypox is less contagious than its cousin, smallpox, anyone who has been exposed to the virus should seek immediate medical attention.

Newborn infants, young children, pregnant women and people who have a weakened immune system (immunocompromised) are at the highest risk for severe disease or complications from monkeypox.

Currently, there is a debate about the claims that monkeypox is a sexually transmitted infection (STI) dominating male communities that engage in sex with other men (MSM). Currently, there is no evidence that supports the cause and effect of monkeypox and STIs.

The vast majority of the more than 1,900 cases of monkeypox documented in the United States report men having sex with other men. It is possible that MSM are more likely than heterosexual men to engage with healthcare providers, which means you would capture more cases in one group and less in the other, but it doesn’t explain the stark disparity. Without this context, it is easy for some—including medical professionals—to paint a picture that stigmatizes non-heterosexual people and behaviors.

Still, these results cannot be completely dismissed for fear of stigmatization, marginalization and discrimination. Medical knowledge and treatment must be administered to this vulnerable population and more research must be done to uncover if there is an STI-like biological component to disease transmission, like the presence of viral particles in semen or if the skin-to-skin contact within these smaller networks is enough to explain this disparity in infection rates amongst MSM communities.

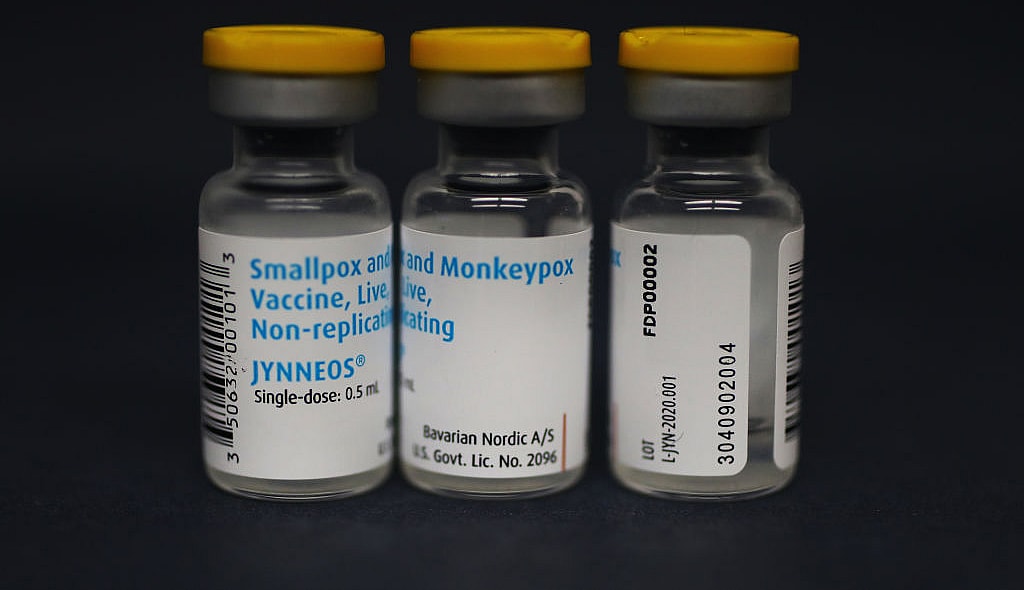

The Monkeypox vaccine

Jynneos is a Food and Drug Administration-approved vaccine that is about 85 percent effective at preventing monkeypox. This vaccine, which may be used for both monkeypox and smallpox, requires two injections four weeks apart for maximum effectiveness. Currently, Jynneos is approved for adults aged 18 and over. Of note, Jynneos is not only effective at preventing monkeypox but it may also be used as a treatment to stop the spread of the virus if given within four days of exposure.

Treatment

Monkeypox is a self-remitting condition that usually resolves on its own. Currently, there is no specific treatment for monkeypox, but symptomatic treatment such as the use of over-the-counter fever-reducers and anti-inflammatory medications for pain relief may be used. Tecorivimat (TPOXX) is an FDA-approved antiviral drug for smallpox that may be used off-label by healthcare providers in high-risk populations to reduce the likelihood of developing severe medical complications. As aforementioned, the vaccine, Jynneos, can also prevent sequelae of the virus if given early in the disease course.

Rumors vs. reality: Learning from HIV mistakes

The initial phases of the monkeypox and the HIV/AIDS epidemics are eerily similar—two mysterious conditions with a high prevalence in small network communities and the challenge of addressing the realities of the medical emergency with appropriate sensitivity and seriousness without alienating an already stigmatized community.

To combat these issues, the public health community has revisited strategies from the botched HIV/AIDS response in the 1980s. First, monkeypox has not been ignored or dismissed due to fear of stigmatization. Instead, increasing knowledge about the condition and ways to prevent it has been at the forefront. Second, the concerted effort of medical journalism to eliminate stigmatizing heads has resulted in few, if any, headlines that insinuate that monkeypox is a disease of gay or bisexual populations.

More needs to be done. Communicable diseases do not care about identities. Any message that fails to lead with science and present a balanced view on the biological and social impacts of the disease, presents a potential barrier to people accessing care. And we simply cannot allow misleading information to affect our quality of life or stifle what little progress we’ve made in public messaging.

Dr. Shamard Charles is the executive director of graduate studies in public health at St. Francis College and sits on the Medical Advisory Board of Verywell Health (Dot Dash-Meredith). He is also host of the health podcast, Heart Over Hype. He received his medical degree from the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University and his Masters of Public Health from Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Previously, he spent three years as senior health journalist for NBC News and served as a Global Press Fellow for the United Nations Foundation. You can follow him on Instagram @askdrcharles or Twitter @DrCharles_NBC.

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku, and Android TV. Please download theGrio mobile apps today!