Editor’s note: The following article is an op-ed, and the views expressed are the author’s own. Read more opinions on theGrio.

Read part one of the series here.

The so-called modern education, with all its defects, however, does others so much more good than it does the Negro because it has been worked out in conformity to the needs of those who have enslaved and oppressed weaker peoples.

— Carter Godwin Woodson, “The Mis-Education of the Negro,” 1933

Fourscore and seven years before George Floyd’s murder, nearly a century before white conservatives declared they had no interest in learning how to be an antiracist, a scant 50 years before scholars coined a phrase to describe Derrick Bell’s legal theories, Carter G. Woodson penned the definitive critique of the eurocentric model of education, “The Mis-Education of the Negro.”

“The thought of the inferiority of the Negro is drilled into him in almost every class he enters and in almost every book he studies,” wrote Woodson. “It is strange, then, that the friends of truth and the promoters of freedom have not risen up against the present propaganda and crushed it.”

When Woodson wrote that Black people were “studied only as a problem or dismissed as of little consequence,” he was not criticizing the white education system; he was criticizing Black educators and Black institutions. As Woodson saw it, Black children were fundamentally harmed by being subjected to a whitewashed education that gerrymandered out anything that didn’t affirm the supremacy of whiteness. “The Mis-Education of the Negro” was based on an inescapable, fundamental truth:

The American education system was created for white people.

Long before Nikole Hannah-Jones imagined “The 1619 Project,” Malcolm X wrote that history had been “so ‘whitened’ by the white man that even the Black professors have known little more than the most ignorant Black man.”

By the time Woodson published his treatise on undoing the miseducation of the negro, South Carolina’s Black citizens had already been doing it for more than a century. Even Martin Luther King Jr. said: “The resistance to the Negroes’ aspirations does not only express itself in obvious method of defiance, but in the subtle and skillful method of truth distortion.” The whitewashing and obfuscation of Black America’s past was so uncontroversial, Woodson wrote an entire book about the subject two decades before white America allowed Black children into its halls of learning.

The Re-education of the Negro

If the miseducation of Black children is an illness, then Dr. Gloria Swindler Boutte has the antidote.

Way back in 2008, the Journal of Negro Education published “Making African American Culture and History Central to Early Childhood Teaching and Learning.” Co-written by Jennifer Strickland, a white graduate student who spent nine years as a preschool and kindergarten teacher in majority Black schools, the article recounts how Professor Boutte changed Strickland’s entire view on educating Black students. Under Boutte’s mentorship, Strickland became one of the thousands of educators using Boutte’s techniques and training to equalize public education. At the heart of the 15-year-old article is the concept of “culturally relevant teaching” or “culturally responsive teaching,” an academic pedagogy Boutte had been pushing in South Carolina’s public schools 50 years after Woodson raised the subject.

As one of the OGs of education equity, Boutte’s curriculum vitae reads like the resume of an education all-star. She is a Fulbright scholar and author of four books on educating Black students. She is also the founder and executive director of the program where Strickland studied, the University of South Carolina’s Center for the Education and Equity of African American Students (CEEAAS). Located at the Palmetto State’s largest institution of higher education, CEEAAS produces “cutting-edge research on teaching effectiveness for African American students by advancing the educational and social welfare of Black students, families and communities.” Boutte also worked on every continent except Antarctica coaching educators around the world on how to smuggle equal education into K-12 classrooms. (Spoiler alert: Strickland went on to teach at historically Black Benedict College, where she taught future Black teachers.)

Boutte was at the center of South Carolina’s pivot toward education equity. School districts contracted CEEAAS and Boutte’s collective of antiracist educators to train teachers in this more effective approach to educating Black children. Individual teachers signed up for her seminars. She was Carter G Woodson’s dream.

“My center has a group of 15 teachers who have been successful using culturally relevant teaching with Black kids,” Boutte told theGrio. ”Cultural competence doesn’t only mean you honor and affirm the kids’ culture; they need to learn about other cultural groups as well. They need to have reflections of themselves, but they also need windows. There’s a whole body of research to show that when we teach kids in culturally loving ways, they achieve better.”

While culturally relevant teaching may seem progressive to some and “leftist” to others, it is not really controversial. Based on the research of Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings, the concept has been around for more than three decades. The Illinois Board of Education voted to train every teacher in the state in the academic principle. When theGrio examined the U.S. News’ 10 highest-ranked universities for education, we couldn’t find a single one that didn’t offer culturally responsive teaching as part of its core curriculum.

“It’s actually a pedagogy — an instructional approach, if you will — to build students’ sense of cultural competence, critical consciousness and … academic achievement,” Boutte told theGrio. “We basically show teachers how to use students’ cultures as a bridge to teach the content they need to teach.”

“A common question asked by practitioners is: ‘Isn’t what you described just good teaching?'” Ladson-Billings wrote in her groundbreaking 1995 article “Toward a Theory of Culturally Relevant Pedagogy” in the American Education Research Journal. “And while I do not deny that it is good teaching, I pose a counter question: Why does so little of it seem to occur in classrooms populated by African American students?”

In June 2021, Boutte was holding one of six virtual trainings for teachers in South Carolina’s Kershaw County School District (KCSD) after the district added courses in African-American history and literature. During the seminar, a parent asked for a copy of Boutte’s training materials. Boutte explained that the slides contained intellectual property, but the participant ignored Boutte and took screenshots. Within days, Boutte’s name popped up on a right-wing website among a list of educators “willing to violate the law to keep pushing CRT.” Within a month, the controversy had exploded into lawsuits, public brawls and an all-out culture war.

“They started filing complaints saying that I was teaching critical race theory,” Boutte told theGrio. “I don’t teach critical race theory; I was teaching them how to teach African-American history. But [a parent] called a meeting and just profiled me. She said that I was teaching critical race theory, that the district is requiring teachers to adopt my books, which is really not true, and basically that I was pretty much like the antichrist.”

To understand how this research-based effort to achieve educational equity for Black children was transformed into a conspiracy theory about a graduate-level legal theory, we must first examine the foundation of America’s education system.

The white education system’s origin story

When Horace Mann, the “father of American education,” began the public education crusade that reformed and reimagined the template for the institution that we know as the American education system, in most slaveholding states, it was illegal to teach enslaved Black people to read. White children in wealthy families had access to private education, while poor, rural and non-white children often reached adulthood without a formal education. Mann believed every child should have access to basic instruction and economic opportunity, without regard to race or class. To do this, Mann based his template on his study of “Prussian factory schools,” which trained unskilled laborers for jobs during the Industrial Revolution. It worked so well. states and local governments trained their teachers on this pedagogy and curriculum at “normal schools.”

It was a perfect system. Teachers only had to learn one method of teaching; students only had to learn one curriculum and wealthy, privileged children were still able to ascend to the station to which they were destined. By deprioritizing individual needs, abilities or background, Mann’s template consistently produced a “punctual, docile and sober” working class. Meanwhile, those who navigated this system could — for the first time in the history of this toddler country — ascend to stations beyond the station to which they were born.

And it worked!

… For white people.

Although there have been minor evolutions, most K-12 schools still use Mann’s two-centuries-old template. Students who thrive inside the cookie-cutter structure are deemed “gifted.” Those who don’t fit into this inflexible system are classified as “learning disabled” or relegated to a lower-tier version of the same-inflexible template. By sacrificing the individual needs of the minority for the economic advancement of the majority, the results reflect privilege and socioeconomic status more than ability or aptitude.

To be fair, it’s understandable why diversity, equity and inclusion evoke fear and concern in the hearts of white parents. The traditional method of schooling has largely worked for white children. If specialized courses in Black history and African-American literature can equalize education, what happens to the kids who prospered under the Eurocentric version of history and literature? They don’t want to upset the cart that gave white children a free ride to social and economic mobility.

The structure isn’t anti-Black as much as it is historically, fundamentally and functionally pro-white. The majority-focused opportunity engine that powers the American Dream was not just by white people for white people; every significant tweak and adjustment that has occurred since its founding was implemented to benefit the white majority.

How to destroy an anti-racist

“The same educational process which inspires and stimulates the oppressor with the thought that he is everything and has accomplished everything worthwhile, depresses and crushes at the same time the spark of genius in the Negro by making him feel that his race does not amount to much and never will measure up to the standards of other peoples.”

— Carter G. Woodson, “The Mis-Education of the Negro,” 1933

When Black people unenslaved themselves after the Civil War, one of their first actions was to lobby for a federal department that tracked education disparities. The U.S. Bureau of Education was created in 1867 but the prospect of equal schools was too much for a country that had just survived a race war. The Bureau of Education lost its independence due to “white resistance to black civil rights, and the waning of federal enforcement in the South.”

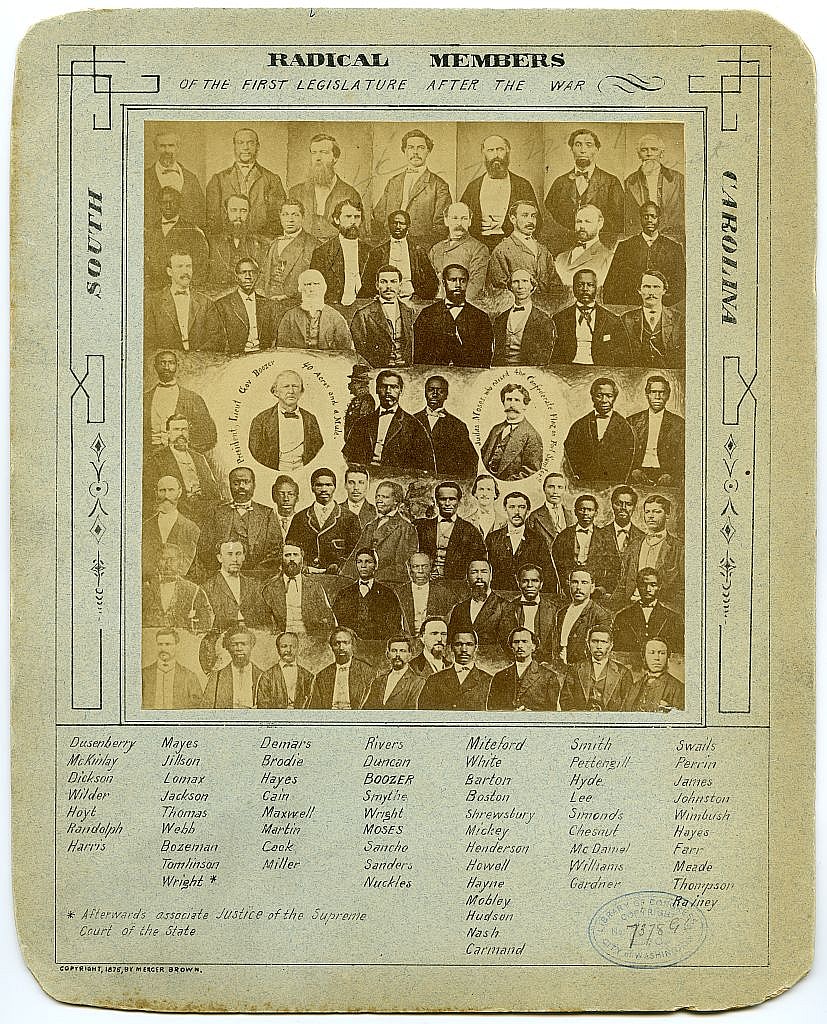

On Jan 14, 1868, 76 Black men and 48 white men gathered in a three-story house in Charleston, S.C. For 63 days, they would compose a state constitution that would get South Carolina readmitted into the United States. At the time, Black children were enrolling in school at higher rates than whites, thanks to the federally supported Freedmen’s Bureau. But the delegates were tasked with creating a system that met the needs of all the state’s citizens.

On March 17, 1868, they finally finished. Unlike the U.S. Constitution, South Carolina guaranteed every male citizen the right to vote “without distinction of race, color or former condition.” It taxed the wealthy, provided rights to women and outlawed debtors’ prisons. Though these ideas were progressive, they were not necessarily new. But when South Carolina’s majority-Black delegation affixed their signatures to this progressive document, they had created one thing that had never existed in America:

The “first free, compulsory, statewide public school system in America.”

The education committee was led by Black educator Francis Cardozo, who said South Carolina’s white leaders “will take precious good care that the colored people shall never be enlightened.” Because Cordoza was elected as secretary of state, the Black founding fathers of South Carolina 2.0 named Justus K. Jillson, a 19-year-old white “Yankee radical” who moved to South Carolina to teach Black children, as the first state superintendent of education.

For 10 years, Jillson fought for equal education. He integrated schools, trained Black teachers and convinced the federal government to invest in state schools. His vision was ultimately thwarted by whites’ fear of Black education. In Jillson’s first report, only one county commissioner supported interracial education. And when Jillson tried to create an integrated school for the deaf, every single teacher resigned. According to historian Ernest McPherson Lander: “Many whites disliked the whole educational program because it was begun by the [Radical Republicans], it implied racial equality, it might ‘spoil’ good Negro field hands, and it might improve the Negro’s political potential.”

After the 1876 election, whites regained control of the South Carolina government and Jillson was run out of the state. Jillson learned what Woodson meant when he wrote that Black children were “educated in a system which dismisses the Negro as a nonentity.” Jillson had failed to achieve true education equality, so he moved back to Horace Mann’s home state of Massachusetts. Overwhelmed by what the Boston Evening Transcript called a “despondency,” Jillson fired two bullets into his brain in 1881.

One hundred and forty years after Jillson’s death, South Carolina’s public educational broadcasting network invited Kershaw County’s superintendent, Dr. Shane Robbins, to talk about education equity. Like the post-Civil War white superintendent Jillson, Robbins was a “Yankee” with a vision for equal schools who moved to South Carolina to educate children.

Appearing on an episode of South Carolina Educational Television’s “Carolina Classrooms,” Robbins rejected Mann’s majority-focused idea of one-size-fits-all education, boldly stating KCSD’s goal of seeing “each individual child maximize their skills and abilities.” In doing so, Robbins also dismantled the conservative argument that striving for equity and inclusion is a Marxist attempt to achieve “equality of outcome.”

“We use the term education equity to identify fairness,” Robbins explained in the episode. “To provide equity in education, we have to put systems in place that are going to ensure that each individual child has an equal opportunity for success.”

Robbin’s next statement would raise eyebrows and push the concerned caretakers of Caucasian education into action:

We hired a coordinator of diversity, equity and inclusion in our district a couple of years ago, shortly after I got here … Her team is working with our teachers on a construct called “culturally responsive teaching.” And, if you dig into the research, you’ll see that many — not all — teachers come from middle-class families. Some of them are second and third-generation educators, so they don’t necessarily have the experience with the different populations or demographics because that’s just not where they come from.

We’re trying to be intentional about training our teachers about the importance of including students’ cultural backgrounds and using those references in all aspects of learning.

In the wake of the 2020 protests surrounding the murder of George Floyd, as school districts, pledged to create more inclusive curriculums, Kershaw County decided to add classes in African-American literature and African-American history to its curriculum. But who would train KCSD teachers on this more inclusive, more effective approach?

Well, appearing in that SCETV episode with Robbins was a world-renown leader who founded an institute for that specific purpose. She was also part of the Anti-Racist Collective, a group of equity-minded educators who contracted with school districts to train teachers in culturally relevant practices.

Her name was Dr. Gloria Swindler Boutte.

After Boutte’s first session, rumors began spreading that KCSD teachers were being forced to learn critical race theory. On July 12, 2021, a group of parents whose children were enrolled in Kershaw County schools met with Robbins to express their concerns. Nine days later, one of the concerned parents, Sheri Few, filed a Freedom of Information Act request for the materials. When the school district denied her request again, citing Boutte’s intellectual property rights, Few filed a lawsuit against the Kershaw County School District.

But the belligerent gang of outraged white women who showed up to object to Boutte’s training was not just a group of concerned moms who stumbled across a critical race theorist in their kids’ schools; they were the newest soldiers in South Carolina’s three-century-old culture war against Black education.

The Head Karen In Charge

If culturally responsive education and critical race theory are the work of Satan, then Sheri Few must be white Jesus.

For decades, the evangelical, gun-toting, pro-confederate, MAGA mom, who declined theGrio’s interview requests, has led the culture war against “anti-American and anti-Christian propaganda and other indoctrination in South Carolina schools.” As the founder of the U.S. Parents Involved in Education (USPIE) a conservative activist organization dedicated to eliminating “critical race theory, explicit sex education, revisionist history and gender confusion,” she helped nationalize the effort to destroy education.

That’s not hyperbole. During her first three unsuccessful runs for political office (S.C. superintendent of education, U.S. Congress and the S.C. legislature), Few campaigned on one goal: to “end the U.S. Department of Education.” Even her conservative backers noted that “Few’s state organization merged with like-minded parents in other states under the name U.S. Parents Involved in Education (USPIE), with the goal of abolishing the federal Department of Education and its education mandates.” The USPIE’s “blueprint” includes ending Pell Grants, privatizing student loans and eliminating Title I, the federal program that provides assistance to low-income schools.

But in South Carolina, Few’s ideas are not considered fringe. She is a mainstream conservative who chaired the Kershaw County Republican Party, served in three GOP governors’ administrations and sat on the South Carolina GOP executive committee. Political candidates seek her endorsement. During her failed 2014 run for S.C. superintendent of education, Few lost the Republican nomination by a scant three percentage points.

By the time Robbins had heard rumors he paid Boutte to infect Kershaw County’s innocent white children, Few had already organized a battalion of angry white ladies and summoned S.C. Rep. Bill Taylor, R-Aiken, who had just introduced an anti-critical race theory bill into the legislature. At the July 12, 2021 meeting, Few insisted that “culturally responsive teaching is the same as critical race theory.” When Robbins tried to explain the misinformation, Few “went back to the microphone and asked him to prove they were not the same.”

How can you prove that a banana is not a bomb?

You could, of course, simply unpeel the banana and show that it’s not a stick of dynamite. But because the training materials were Boutte’s intellectual property, Robbins couldn’t. It was too late, anyway. He had already uttered the dreaded words “diversity, equity and inclusion,” and Few had already branded Boutte as a “CRT teacher.”

Before the next school year began, Robbins was gone. He would leave Kershaw County to take another job in South Carolina. During the hiring process, Robbins was forced to address “concerns brought to the board” from Few’s acolytes. His new bosses assured parents that Robbins was not bringing CRT, diversity, equity or inclusion along with him.

And that’s how culturally responsive teaching became critical race theory.

“I lost the contract with the governor’s school along with other contracts,” Boutte said. “People perceive me as a big threat because they know the work I do statewide and nationally. And it’s not just with white administrators. One principal, who’s a Black man, said: ‘I can’t take this. They got your name all up in the General Assembly!’”

In April 2022, Few dropped out of the race for state superintendent of education, her fourth failed attempt at holding elected office, claiming “logistical” reasons. In reality, Few had no choice but to end her campaign because, according to the state laws she championed so often, Few was wholly unqualified to lead the state Department of Education. South Carolina requires that its superintendent hold a master’s degree and well…

Few does not have any credentials.

That’s right; the “get-rid-of-the-Department of Education” lady does not have an education in education. Even before she dropped out of college, she was studying German. While not having a degree doesn’t make her any less of a person, Few’s entire political movement is predicated on contradicting educational experts and their “workforce development” techniques.

But Sheri Few did not ride quietly into the good night. A few days after Few ended her candidacy, former Education Secretary Betsy DeVos joined the movement, declaring her support for abolishing the U.S. Department of Education. Like Few, DeVos had no previous experience in education. When Few dropped out, she gave a full-throated endorsement to Republican Ellen Weaver, who went on to become S.C. superintendent of education. USPIE has also repeatedly signaled its support for Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis. Meanwhile, Few is selling a documentary, “Truth & Lies in American Education,” for the low price of $19.95.

These are the two opposing factions in South Carolina and across the nation. One side has people with expertise, education and experience. In Dr. Boutte, they have a world-renown expert who has done the work. They have people who have dedicated their lives to eliminating racial disparities. One side has history and research and truth and three centuries of incessant longing for liberty.

The other side has whiteness.

They have a white man named Christopher Rufo. They have a white lady named Sheri Few and another named Betsy DeVos. They have Ron DeSantis and Donald Trump but they don’t have facts. They don’t have data or science or knowledge or truth or history or experience or anything that makes them qualified to lead a conversation about educating Black children.

“Of course, they reduce it to: ‘It makes kids feel bad.’” Boutte explained. “Well, when you say ‘kids,’ whose kids are you talking about? Which children are so uncomfortable? Black kids feel uncomfortable all the time in public schools. All kids do. Algebra is uncomfortable. Biology is uncomfortable. And, yes, history is uncomfortable. It’s supposed to be. That’s why we teach it; so we won’t keep making the same mistakes. And, maybe one day, Black kids won’t have to feel uncomfortable.”

On June 4, 1868, a newly formed white supremacist terrorist cell called the Ku Klux Klan burst into a South Carolina home and opened fire, killing two: Solomon George Washington Dill and Nestor Ellison. Dill, who the U.S. secretary of war described as a target of a “social and political warfare waged against him, bitter and unrelenting,” was assassinated because of his advocacy for equal rights for Black citizens. Apparently, he traveled around the state advocating for equal rights for the state’s Black majority.

But the racists who opposed equal education could not erase Dill from history any more than they could erase Justus K. Jillson’s name. Jillson’s legacy did not begin when he became South Carolina’s first superintendent of education; Dill’s legacy did not end when he became a county commissioner. Justus Kendall Jillson’s and Solomon George Washington Dill’s signatures are forever affixed to South Carolina’s great Black anti-racist constitution of 1868.

They represented Kershaw County, S.C.

One hundred fifty-five years later, the county’s Black children are still fighting for equal education.

In the next part three of our series, this war will claim a new victim.

Correction, May 24, 2023, 5:30 p.m.: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that Gloria Swindler Boutte was a MacArthur “genius” grant recipient. The story has been updated.

Michael Harriot is a writer, cultural critic and championship-level Spades player. His book, Black AF History: The Unwhitewashed Story of America, will be released in September.

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku, and Android TV. Please download theGrio mobile apps today!