When four gunshots rang out one summer in Brownsville, a group of people ran toward the sound to prevent any bloodshed — but they weren’t police officers.

This group, known as violence interrupters, is part of an experiment designed to place community members on the front lines, deescalating situations that law enforcement would typically respond to first.

They are the focus of “Policing Our Own,” a forthcoming documentary by screenwriter and filmmaker Dante DeBlasio. DeBlasio, 26, says he wanted to shine a light on these violence interrupters to showcase the power of alternative approaches to reaching the community.

“It’s not just about community members responding to calls for help; it’s about offering on-the-ground resources too — everything from access to therapy to helping people register to vote,” DeBlasio says in an interview with theGrio.

In the 18-minute documentary, DeBlasio highlights how NYPD officer Terrell Anderson developed the Brownsville Safety Alliance (BSA) program, which allows violence interrupters to take over certain police calls.

“A police officer came up with what most people would consider a very radical public safety experiment,” DeBlasio tells theGrio.

The film primarily follows Dushoun “Bigga” Almond, a violence interrupter who turned his life around after serving time for armed robbery. Almond uses the credibility he earned on the streets to become a trusted figure in the community, defusing conflicts with his larger-than-life personality and genuine concern for others.

In the film’s most moving scenes, Almond leverages his charisma to deescalate tense situations, showing empathy and understanding.

“Violence interrupters are often people who were formerly incarcerated or gang members who may not have access to the traditionally ‘desirable’ jobs in society,” says DeBlasio. “Many don’t have college degrees, but if you can provide them with jobs that allow them to positively impact their communities, it’s a win-win.”

DeBlasio believes that these nontraditional methods can prevent deadly encounters with police officers who may not yet have earned the trust of community members or who might be interacting with individuals experiencing a mental health crisis.

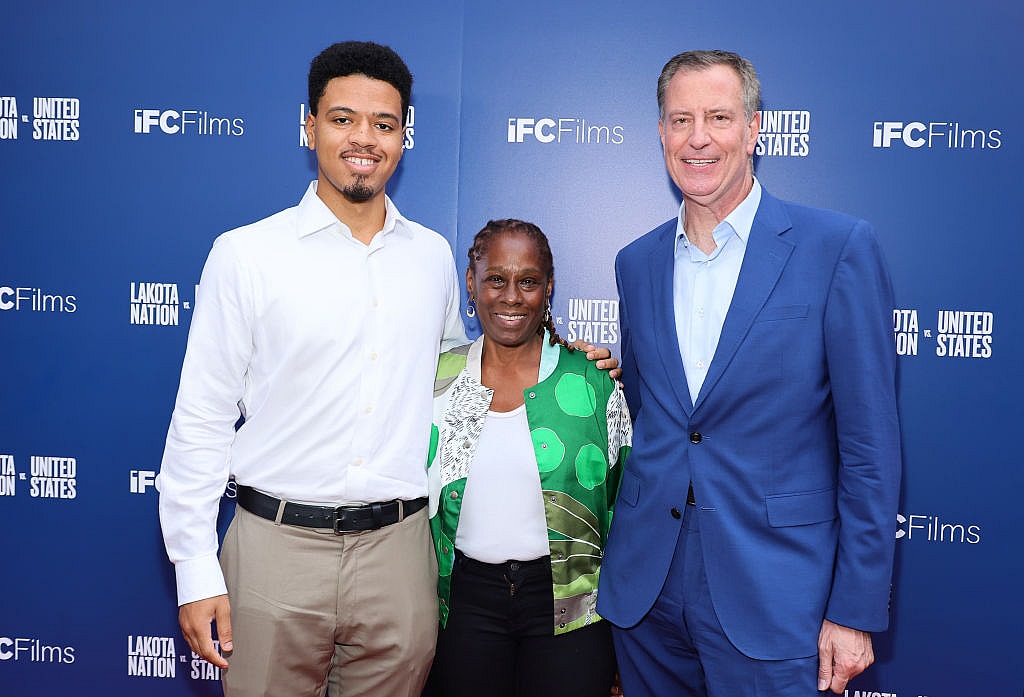

As the son of former New York City Mayor Bill DeBlasio and activist Chirlane McCray, Dante says his personal political experiences have shaped his views on public safety.

“You could argue that the defining issue of my dad’s first mayoral campaign in 2013 was ‘stop and frisk,’” DeBlasio recalls. “I was in his commercials, speaking out against that policy… Growing up in the political world, I spent a lot of time talking to figures in policing and public safety. It gave me an appreciation of what all sides are trying to accomplish, their successes, and the challenges they face.”

Other cities have documented success with violence interrupter programs. In Chicago, for instance, it’s estimated that for every dollar invested in these programs, the city saved $3 to $5, according to the Giffords Center for Violence Intervention. These savings are crucial when considering that gun violence is estimated to cost the U.S. around $280 billion annually.

In 2022, the Biden-Harris administration called for increased investment in community violence intervention, and Congress made history by earmarking $50 million to fund programs focused on violence interruption.

Through public education on the impact of violence interrupters, DeBlasio hopes to inspire greater investment in similar initiatives. “Policing Our Own” is expected to make its public debut through a film festival, and DeBlasio is looking to partner with organizations that are willing to amplify the project.

“I’m not suggesting that violence interrupters should replace the police or that law enforcement doesn’t play a critical role in society,” DeBlasio tells theGrio.

“The name of the game has to be cooperation, and it has to be empowering organizations like these that want to make a difference in the communities, that do make a difference in their communities.”