GREENSBORO, N.C. (AP) — Strewn across the coastal plains and backroads of North Carolina lie institutions that could be pivotal in the battleground state in Tuesday’s elections — 10 historically Black colleges and universities steeped in a history of activism.

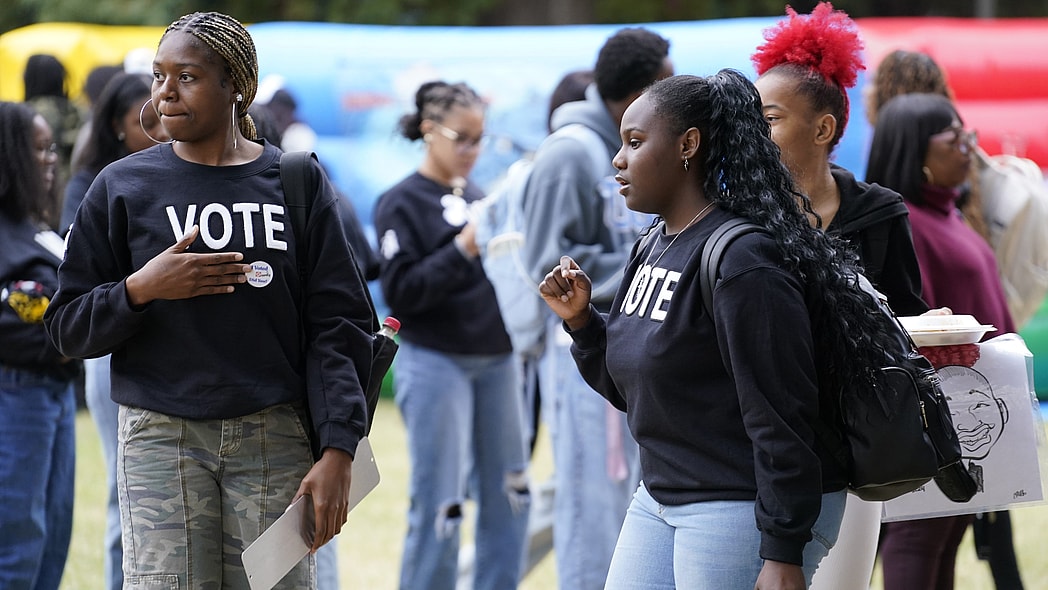

Now, local student government associations and other organizations at these schools have mobilized in a full-on effort to galvanize a nearly 40,000-student voting bloc. They’re doing so as an HBCU graduate — Vice President Kamala Harris — is running for president.

In the leadup to Election Day on Tuesday, the North Carolina Black Alliance has been working with each HBCU, and one predominately Black institution in the state, to mobilize and transport students to the polls throughout the early voting season.

The Votecoming tour is a play on HBCU homecoming season, a sacred tradition at the schools. The hope is to inform students of who and what is on the ballot from top to bottom and get students to vote early so they can avoid any voter ID or registration problems, said Gabrielle Martin, the alliance’s campus coordinator.

The effort is non-partisan. But there’s no question that the presidential candidacy of Harris, an HBCU graduate herself (from Howard University) is driving excitement.

Having Harris at the Democrats’ helm puts positive attention on HBCUs and gives them a seat at the table, said Justin Nixon, a senior and student government president at Johnson C. Smith University in Charlotte. “We’ve always said what we’re capable of, but now, especially, we can truly say that this is the clear representation what an HBCU can produce and has produced.”

Still, students say their effort is about civic engagement, not taking sides.

“It’s really crucial, especially during an election like this, for us students to actually be taking the reins on something so important,” said Kylie Rice, a senior and student government president at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University in Greensboro, the state’s largest HBCU.

Recommended Stories

“We stand on the shoulders of giants, and we realize the civic footprint that was left for us. Now, it’s up to us to actually fulfill and keep that same momentum going forward.”

North Carolina’s HBCU students have spearheaded civil rights movements for decades.

For example, students at Bennett College in Greensboro, one of two all-female HBCUs in the country, protested a local movie theater in the late 1930s because it would edit Black people out of films. In 1960, women from Bennett, known as Bennett Belles, were joined by North Carolina A&T students to protest at a local lunch counter.

“I feel like we’re making our past Belles, our big sisters, proud and happy because they were behind so many movements and now we’re here to make history ourselves,” said Lanell Jones-Huddleston, a junior at Bennett.

This spirit of activism hasn’t slowed.

In 2019, Black communities in North Carolina were gerrymandered, notably in Greensboro, Charlotte, and other cities, in a process that diluted their electoral power. North Carolina A&T students were impacted because the university was split in half and rallied against the maps in response.

North Carolina is also saddled with voter ID court battles and, now, Hurricane Helene destruction that residents worried could hamper voting.

“We want to hype up early voting so if there is a registration issue or an ID issue or a voting issue, period, the students will have time for recourse so that their vote can still count,” Martin said.

The tour kicked off Oct. 17, North Carolina’s first day of early voting, at Shaw University. It ends at Fayetteville University on Friday.

Local HBCUs have also hosted several other engagement events, including teacher-student voter information sessions at Bennett College, class wraps to explain the importance of voting at Elizabeth City State University, and various game nights with Black fraternities and sororities.

North Carolina is seemingly up for grabs since Republican Donald Trump ’s margin of victory here was just 74,481 votes in 2020, the tightest of any state he won over Democrat Joe Biden.

“That’s a razor-thin margin and North Carolina HBCUs alone are a significant voting bloc,” Nixon said. “So, we play a large role in shaping the dialogue around politics and around issues within the Black community.”

The Harris campaign is on an HBCU homecoming tour, which includes a stop at Shaw. The Trump campaign also plans to reach out to HBCU students directly, highlighting initiatives like the law he signed as president to establish permanent HBCU funding, said Janiyah Thomas, the Trump campaign’s Black media director.

The push to muster young voters makes North Carolina HBCU students a force in the campaign’s final days. “We’re Gen Z also and for us, it’s the first time we’ll have a say,” said Jazmin Rawls, 20, a Bennett sophomore who introduced Harris in Greensboro in September and will be voting for the first time.

Having a say in what may be the most consequential election to date prompted Shelby Fogan, a senior and student government president at Bennett, to change her voter registration from her home state in Ohio to North Carolina.

“I voted absentee in Ohio last year for local elections, but I had to ask myself for this election, where is my vote going to count the most?” Fogan said. “For me, it’s North Carolina. We really should consider where our votes will have the most impact.”

Students want to know which candidates locally and federally will fight best for HBCU funding. These schools historically struggle financially, despite recent influxes in money.

Bennett lost its accreditation in 2019 due to its financial standing. Without accreditation, colleges can’t participate in federal programs, like student aid. Bennett received its accreditation back in 2023.

HBCUs have lower tuition costs, giving Black students a greater opportunity to go to college, so the issue is important, said Aleah Crawford, a junior at Elizabeth City State University.

“Our funding is at stake,” Crawford said. If that’s lost, “people have to figure out how to pay out of pocket to go here and depending on your economic status, that basically chooses if you can go to college or not.”

Elizabeth City is in a rural area that can get overlooked by political candidates. With fewer than 2,200 students, the school is the only local four-year college and contributes heavily to its growth, but students don’t always feel considered, said Caszhmere Chaison, a junior and student government official at the university.

“We really have to focus in on us and our student body because we bring so much financial backing for this city,” Chaison said. “Not everybody looks at us as a part of the city. We have to make sure that we’re advocating for ourselves because if not us, then who?”

This sentiment ripples throughout the HBCU community nationwide.

What students have to do now is use their vote, said Bennett’s student government president, Suzanne Walsh.

“Our role,” Walsh said, “is to say, don’t overlook us.”