VIDEO: Five Mualimm-ak on incarceration with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder

On the new theGrio series, "Unheard," Mualimm-ak, executive director of Incarcerated Nation Network, talks about his time confined.

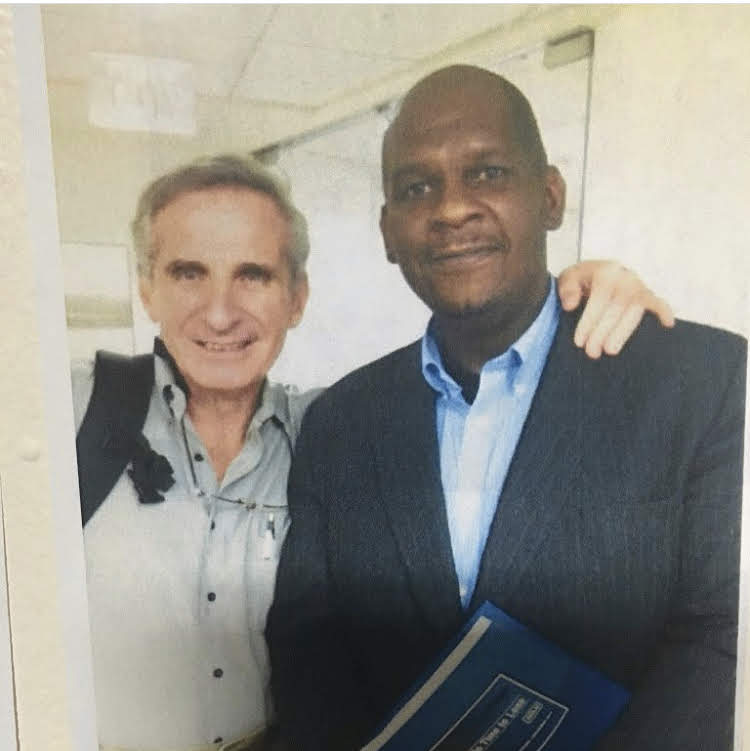

Activist, mental health advocate and executive director of Incarcerated Nation Network, Five Mualimm-ak, lives with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. He was incarcerated across New York City jails, county facilities and upstate, serving a total of 12 years, including time in solitary confinement.

In an interview for theGrio’s new series, “Unheard,” Mualimm-ak opens up about his time incarcerated and the treatment of people in prisons and jails with mental health conditions.

“I don’t think that there’s a functional space for people with mental health inside of correctional systems,” says Mualimm-ak. “The sort of confinement, it’s all triggering. It’s all hard to survive.”

“Prisons can adversely impact those with mental health disorders from the very ideology in that our current prison systems were not built to serve people that do have mental health,” Dr. Ulrick Vieux, a board-certified psychiatrist, told theGrio.

“What happened is the unintended consequences of policies that were enacted in the ’60s, ’70s and ‘80s,” he said. “The unintended consequences were what happens if you close asylums, if you deinstitutionalize mental health treatment facilities? What are you going to do with this population? And unfortunately, a lot of this population is actually being treated within the jail and prison system.”

Vieux also shared how the modalities that are utilized in prison can be problematic.

“The concept of isolation, solitary confinement,” he said, “a person that’s suffering from a disorder such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, [isolation and solitary confinement] can make this worse.”

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, “about three in five people (63%) with a history of mental illness do not receive mental health treatment while incarcerated in state and federal prisons. It is also challenging for people to remain on treatment regimens once incarcerated. In fact, more than 50% of individuals who were taking medication for mental health conditions at admission did not continue to receive their medication once in prison.”

Inside of prison, Mualimm-ak revealed, there isn’t any connection to treatments someone may have had before incarceration, nor is there a mental health assessment. He opened up about his experience with lithium, a medication known as a mood stabilizer.

“With bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, they gave me lithium,” says Mualimm-ak, “which of course, was a bad medication, gave me a rash. You react to that rash. It’s like, ‘Hey, I don’t want to take this because it’s causing me physical harm.’ They’re saying, ‘Well, you obviously don’t have a mental harm if you don’t want to take this medication.’

“It becomes this sort of state where people inside end up having to prove that they have a problem just to be sort of treated for that problem,” he maintains. “The treatment is minimal, and it’s the only medication they prescribe or the generic version of that.”

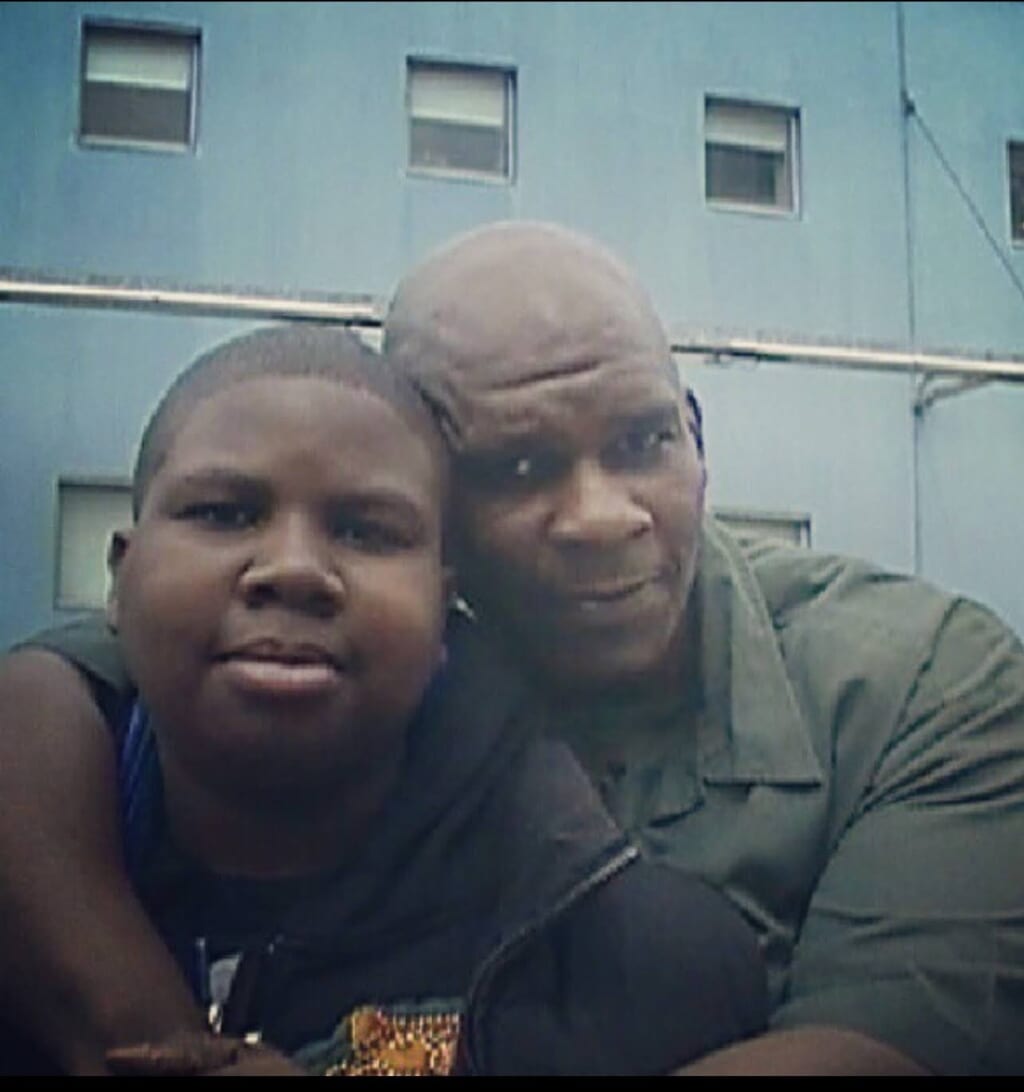

(Photo: Courtesy of Five Mualimm-ak)

Talk therapy, emotional support and speaking with a psychiatrist who can properly diagnose the delusions are ways Mualimm-ak shared could help keep him grounded in reality.

“I think the strongest point is family,” he says. “So that exclusion from my kids, from people who understand me, from people who know what you’re going through, that type of support is a void in prison.”

“You end up decompensating by yourself. You end up having this sort of personality shift by yourself. And this is on top of the many mood disorders and mental conditions that prisons and jails cause on a normal basis,” he shares. “For me, it was hard to thrive without those supports, so I just kept spiraling down, talking to myself, writing on the walls and drawing because it was like my only outlet. And even all of that is punishable.”

When asked what he feels needs to be done to help those who have mental health conditions and are incarcerated, he says, “they shouldn’t be there in the first place.”

“When you look at a person’s diagnosis and their conditions, and if their crime associates with their conditions, they shouldn’t be incarcerated in the first place,” opines Mualimm-ak. “I think that besides adequate mental health care, there’s not enough treatment that goes on in facilities.”

The activist believes prison and solitary confinement is a mental-health-producing system. With Incarcerated Nation Network, he is doing the work, helping those formerly incarcerated of all ages integrate back into society and demanding an end to the inhumane treatment that takes place in the prison and jail system.

“[Solitary confinement] actually causes anti-social personality disorder, diseases, you’re going to have arthritis,” he says. “You may have type 2 diabetes just from being in that compressed environment.”

“People leave out there with all kinds of triggers and traumas, and I’ll never be the same,” Mualimm-ak maintains. “They say, ‘Oh, you are a solitary survivor,’ but nobody survives. It’s really asking you, ‘How damaged are you or how much damage have you received?'”

Check out the full episode above.

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku and Android TV. Also, please download theGrio mobile apps today!