Editor’s note: The following article is an op-ed and the views expressed are the author’s own. Read more opinions on theGrio.

“How come ain’t no Black people performing in this hotel,” Chris Tucker asked in 2001’s “Rush Hour 2.” When the casino manager told him Lionel Richie was performing that evening, Tucker loudly replied, “Lionel Richie ain’t been Black since the Commodores, man!”

While the scene was for laughs, as always, there’s truth in jest. This joke about Richie leaving the Black, funky confines of his hitmaking band from Tuskegee, Ala., to entertain the masses with the pop sound of his solo work has circulated in Black households for decades. It’s a microcosm of the ideal that when Black artists go pop, they are sellouts.

It’s understandable and justifiable why fans and critics often malign Black artist participation in pop music and, in some cases, other artists. In 2021, R&B and Broadway legend Stephanie Mills cautioned young R&B singers that they could face irreversible banishment from the Black community if they chose to record pop music.

“I just want our young entertainers to stay Black, stay who you are. Don’t want to go over there and be pop,” Mills told theGrio. “Stay true to your music. That’s very important. Don’t sell out. Don’t sell out because we don’t want you when you sell out. You keep your ass over there. Don’t come back over here.”

Mills’ sentiment echoes many others. Pop music has a history of sanitizing Black genres for the consumption of white consumers for centuries. However, what complicates things is that contemporary pop music sounds the way it does because of the innovation of Black artists.

When a Black artist makes pop music, are they selling out or reappropriating something taken from them?

The Black community’s resentment of pop music stems from various reasons. Pop music, or popular music, in and out itself, exists because of minstrelsy. White singers and performers would dress up in Blackface, performing as extreme caricatures of Black Americans and enslaved people during the 1800s. Jim Crow, the shorthand for the systematically racist laws in the nation, was a creation of Thomas Dartmouth Rice, a white actor who crafted him in minstrel performance as a stereotypical depiction of a poor Black man.

From there, songs written and performed during minstrelsy became among the first “pop songs,” like “Turkey in the Straw” (used as ice cream truck jingles), “Dixie Land,” and later, “Oh Suzanna.” Following the end of the Civil War, minstrelsy got so popular that Black performers joined in, like the Georgia Minstrels.

The idea of Black Americans performing as lowly caricatures of themselves for the appeasement of white Americans is a traumatic reaction to the indoctrination and psychological terrorism inflicted on Black Americans that traveled across generations. One could argue that the stigmatized imagery of the toxically masculine rapper — today’s pop music — who glorifies violence, materialism and aggressive promiscuity is an example of modern-day minstrelsy, as it plays into the stereotype of the contemporary Black urbanized man.

Throughout history, white record label owners, producers and gatekeepers have engaged in a cycle when it comes to Black music genres. In order, they condemn it, co-opt it, homogenize it, commodify it, then mass produce it until the genre becomes the property of the white performers. This is true with rock, jazz, disco and others.

With this knowledge, it’s no wonder why so many Black people denounce pop music when it comes from one of their own. Black genres like gospel, blues, dancehall, bebop, boogie-woogie and so on possess a spirit of longing, poignancy and exuberance that distinguish the lyrics and the vocal and instrumental attack from any other music. The problem is that over time, white artists either see this pure Black expression and recreate it as a farce or fascination.

Women like Big Mama Thornton, Hazel Scott and Sister Rosetta Tharpe were the pacesetters for white artists who recorded rock and roll and popularized it for a mass audience. Sam Phillips, Sun Records founder, infamously said, “If I could find a white man who had the Negro sound and the Negro feel, I could make a billion dollars!” He produced artists like Elvis Presley and Jerry Lewis, who reinterpreted jump blues to make the kind of rock and roll they were associated with. (Sam Phillips biographer Peter Guralnick wrote that his quote was taken out of context, but the biography is titled “The Man Who Invented Rock & Roll,” so … )

But this is where the complexities come into play.

Like rock and roll, pop music is often used as a catch-all term to describe the most famous music at the time. It doesn’t necessarily mean it’s pop. In the 1990s, numerous R&B artists could crossover into the pop charts without diminishing the essence of their Blackness or sound.

For instance, Keith Sweat achieved two top-five singles on the Billboard Hot 100, “Twisted” and “Nobody” in 1996. It’s fair to say that neither of these songs sacrificed the Black elements that Sweat employed in his music since 1987, yet it still found an audience with white listeners.

On the flip side, you have The Weeknd. He emerged in 2011 as a mysterious singer-songwriter whose ominous, atmospheric sound was dripping with R&B trademarks. However, by 2015, he began collaborating with Max Martin, the Swedish songwriter behind pop hits like Backstreet Boys’ “I Want It That Way” and Britney Spears’ “…Baby One More Time.”

Some could argue that for The Weeknd, who was already making Black music, to team up with a man who made songs that were sanitized versions of Black music, it had to be only to gain favor with white consumers. Indeed, The Weeknd earned his greatest success with Martin on songs like “Can’t Feel My Face” and “Blinding Lights,” but his muse was actually a Black man named Michael Jackson.

The Weeknd has always been upfront about Jackson being an inspiring agent for him, from covering his hit “Dirty Diana” to giving homage to “Billie Jean” in his video for “Sacrifice” and recording much of his latest album, “Dawn FM,” at Westlake Audio, the studio where Jackson and producer Quincy Jones recorded landmark pop albums “Off the Wall,” “Thriller” and “Bad.”

Jackson, who is known as the King of Pop, achieved this reputation because he and Jones were able to organically synthesize various Black genres and present them in a way that was both authentic to Blacks and digestible for whites. This illustrates that much of the Black troupes found in pop music are innovations of Black artists.

Much of what makes pop music so infectious to so many are elements that stem from Black things: swing, syncopation and improvisation. Ragtime godfather Scott Joplin, jump blues icon Louis Jordan and trumpeter Louis Armstrong were among those who introduced the elements mentioned above that were incorporated into popular music practiced by whites.

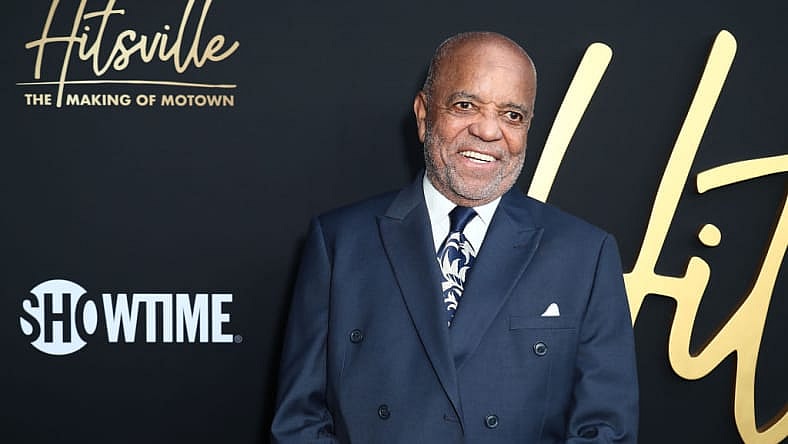

Later on, Black labels like Chess Records and Motown began to define the prototype of current pop. Berry Gordy’s stable of Motown songwriting teams like Holland-Dozier-Holland took the swing, syncopation, call-and-response, and improvisation and applied to it savant-level songcraft and arranging, with agile house musicians the Funk Brothers, who fluently understood the sonic dialects of blues, R&B and jazz that made the label’s catalog the new American Songbook.

Pop music is both a catch-all for any popular music to the masses and a stand-alone genre with sonic signatures. Those signatures incorporate Black innovations of swing, syncopation and improvisation; another signature also removes much of the depth and spirit in the Black genres it borrowed from.

The ultimate irony is that the Black community gets angry when Black artists like Tharpe, Thornton, and Jordan don’t reap the economic benefits for innovating a sound that white artists do after they co-opt it, but the community gets skeptical anytime a Black artist like Richie or Whitney Houston is loved so hard by a white audience.

If a Black artist is making that kind of music to gain a white audience, it’s understandable that they would be deemed a sellout. But considering everything that whites have taken from Blacks, aren’t we due to claim something of theirs for our own?

Matthew Allen is an entertainment writer of music and culture for theGrio. He is an award-winning music journalist, TV producer and director based in Brooklyn, NY. He’s interviewed the likes of Quincy Jones, Jill Scott, Smokey Robinson and more for publications such as Ebony, Jet, The Root, Village Voice, Wax Poetics, Revive Music, Okayplayer, and Soulhead. His video work can be seen on PBS/All Arts, Brooklyn Free Speech TV and BRIC TV.

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku, and Android TV. Please download theGrio mobile apps today!