You should visit South Carolina’s new International African American Museum before it’s illegal

OPINION: Charleston’s new International African American Museum showcases the “woke” CRT history that white people feared would make them feel bad.

Editor’s note: The following article is an op-ed, and the views expressed are the author’s own. Read more opinions on theGrio.

“We acknowledge the history of genocide and forced removal that enables us to occupy this space,” said 9-year-old Paige Berry from atop the stage. A few eyes immediately glanced toward the floor. Some attendees shifted in their seats as if the truth made them feel uncomfortable. In front of me, an elder muttered a traditional phrase of affirmation in her native Gullah language.

“Amin,” she whispered as Berry continued:

We acknowledge that we are gathered here within spaces created through the labor and ingenuity of the Africans who were enslaved to build Charleston and the Lowcountry, its lands and its institutions. We acknowledge that, on this site, Africans and African-descended people were bought and sold and stripped of their autonomy. As we attempt to honor the skill of their labor, the beauty of their artisanship and the relentless perseverance of their identity that has impacted and still impacts our culture today, we acknowledge that these lives and these cultures have always mattered.

Thus began Saturday’s dedication of the International African American Museum (IAAM), the brand new, 22,280 square-foot museum that chronicles the impact and history of Black Americans.

Located at Gadsen’s Wharf in Charleston, S.C., where an estimated 90% of the Americans who descended from enslaved Africans can trace their origin story on this nation’s stolen soil, the IAAM’s Saturday ceremony was 20 years in the making. While I prefer to use the statistic that 40% of enslaved Africans actually disembarked in Charleston, two of the museum’s invited dignitaries used the 90% number in their speech, which includes temporary stops, familial connections and the entire human trafficking network connected to the port called the “capital of the slave trade.” Anyway, I’m sure the couple knew what they were talking about …

Some folks named Barack and Michelle Obama.

In many ways, this new institution serves as a prequel to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture and a starting point for all Black history museums. Although the IAAM is colloquially known as the “slavery museum,” it celebrates the international roots that extend beyond this country’s unique race-based, constitutionally enforced human chattel system. It chronicles the African, Caribbean and worldwide influences that built American history — from the first cash crops to the building of a global superpower. And it does it by correctly centering South Carolina as the unofficial capital of African America.

For three and a half centuries, without fanfare or credit, Black South Carolinians and Black Americans everywhere tried to tutor this country on building a true democracy. If you understand that protests are a form of free speech, thank Edwards v. South Carolina, (If you wanna do it personally, I can give you my aunt Nell’s phone number, the youngest protester in that landmark Supreme Court case). Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott is a great American story, but the legal case for the boycott never reached the Supreme Court. Instead, the justices essentially said: “We decided this issue two years ago when Sarah Mae Fleming did it in S.C.” America’s first free, compulsory public education system? Black South Carolinians did that first. Who filed the first case that ultimately desegregated public schools? You’re welcome.

My paternal grandmother was an African-American museum.

Inez Williams was geechier than the Charleston Geechees. Before she moved to the area and gave birth to children who fought in America’s great war — the Civil Rights Movement — she lived in Colleton County, S.C., less than three miles from where every previous generation of her Geechee Gullah ancestors was enslaved. Her forefathers and mothers were forced through violence and the threat of violence to engineer the Carolina Gold mines that gave free, white South Carolinians the English colonies’ highest per capita income. Needless to say, she did not suffer fools and liars.

I’d never seen her without an apron, and she was the prototype for “I said what I said.” Her Geechee accent was as hard, fast and unforgiving as her demeanor and her technique for combing my childhood afro. She refused to even repeat herself to the uncultured souls who couldn’t understand the history hidden in her tongue. Whenever I asked her to translate, she’d do this thing where, instead of facing me, she’d pull me to her side, burying my face into her hips, and say: “Oohnuh yerrih fuss’im, wuh tank yerrih Iffin messeyuh gehn?” (If you didn’t understand it the first time, what makes you think you’ll understand it if I say it again?)

My cousin Kim, who lived in New Jersey and was less familiar with the accent than I was, finally explained that I was doing it wrong. She advised me to just shake my head and pretend to understand when my grandmother spoke in cursive. (No seriously, I thought … never mind). But when I employed Kim’s strategy, I could tell by the force of her apron tug that she was furious. “Yeen finnuh siddehn jiss sturreh bwoh,” Grandma said through clenched teeth. “Chews’un. Eevah beah Liemout uh foolup buhnah boffum.” Miraculously, I instantly understood her advice: Never pretend to understand something you didn’t. As she put it: “You can choose to either be a liar or a fool; never be both.”

The International African American Museum comes into existence at a time when people across the country, and the Palmetto State in particular, have chosen to live simultaneously as liars and fools. While Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis has built his brand around eliminating “wokeness,” South Carolina’s “Don’t Say Gay” law is 35 years old. South Carolina legislators introduced an anti-critical race theory bill seven months before Florida lawmakers filed theirs. For five years, former S.C. governor Nikki Haley dismissed calls to stop flying the confederate flag at the capital. It took a racist massacre to make her change her mind. Now that she’s running for president, Haley has called on governors to ban uncomfortable parts of Black history because it tells white kids they’re bad and makes victims out of Black children. Her fellow South Carolinian presidential contender, Sen. Tim Scott, once told me that he doesn’t think systemic racism exists. I know he would understand my grandmother if she called him “ol limmout innee foolup” and told him to “chews’un.”

Tim Scott is from North Charleston, S.C.

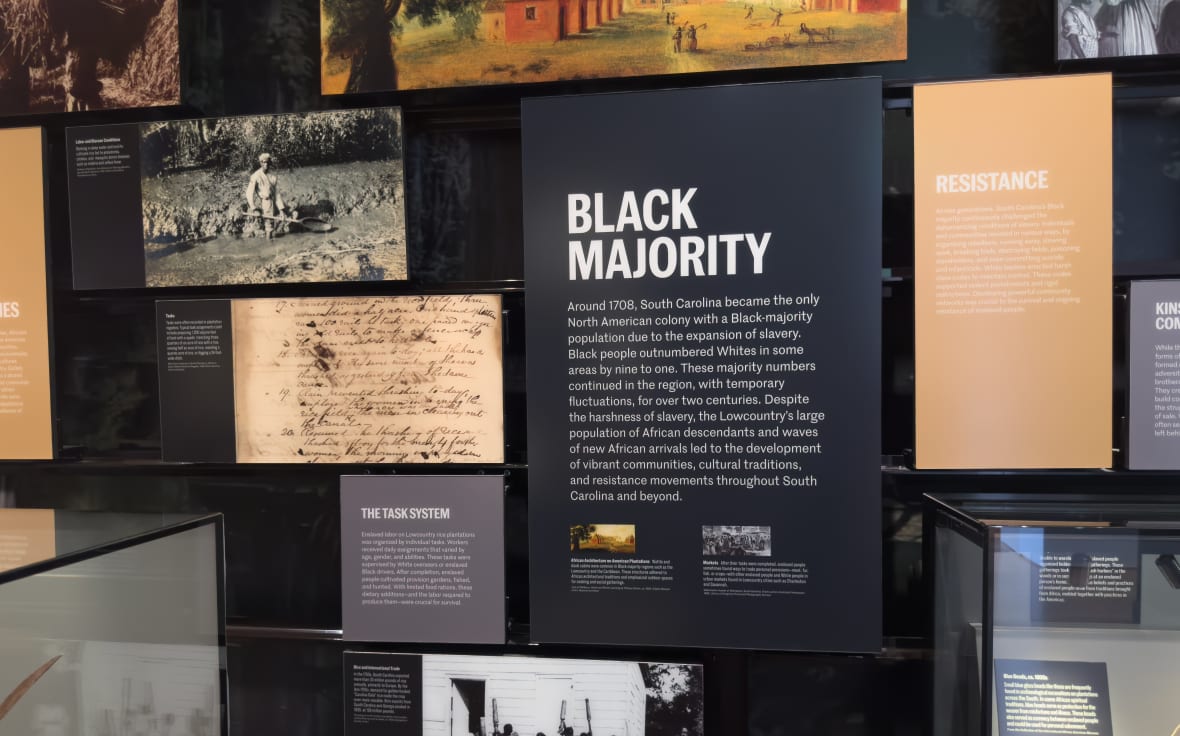

What does this have to do with a slavery museum? Well, Tim Scott says educating kids on systemic racism is “a dangerous, offensive, disgusting message to send to our young people today.” He might be offended by the IAAM exhibit that shows how Black freedmen built and funded their own schools because of a racist system that stole Black taxpayers’ wealth for the use of whites-only schools. Haley might ban the museum’s “Black Majority” exhibit. How could she explain flying a white supremacist symbol in a state that was majority Black for most of its existence? Would Ron DeSantis convict Paige Berry of first-degree wokeness? How could anyone — Black or white — witness what white supremacy has wrought and not feel uncomfortable?

Perhaps the greatest entitlement that whiteness affords is the comfort of being unaffected by ignorance. Learning, growth and progress are supposed to be uncomfortable. It’s why teachers assign difficult math problems and medical residents sacrifice sleep. It’s why weightlifters grunt and marathon runners don’t have nipples. And yes, this museum and its depiction of the bloody, beautiful, interminably long Black struggle is supposed to make people feel uncomfortable.

Black children have to pretend to be amazed by the triumphs of obscure white people like Paul Revere who changed history with his ability to ride a horse and yell at the same time. They are never asked to consider if Bostonians were “playing the victim” when they looted and rioted during the Tea Prices Matter protests in 1773. I’m uncomfortable with Abraham Lincoln’s declaration that he was “ as much as any other man … in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race.” But there is a more important part of the historical narrative that this museum confronts head-on.

My maternal grandmother was an African-American museum.

Every Sunday, my aunts, sisters, cousins and my grandmother Marvell Bradley Harriot and I climbed into a stereo-less station wagon for our weekly trip to visit our family in “the country.” Many of our “kinfolk” still live in Lee County, S.C., where our ancestors toiled to build the wealth of James Bradley, a wealthy planter who never planted a seed in his life. From her honored position in the front passenger seat, my grandmother would play a cassette tape player that was physically incapable of playing anything other than church songs and sermons. Years before white people discovered the phrase “stay woke,” I got my grandmother a recording of Martin Luther King Jr.’s second-to-last speech “Remaining Awake Through a Great Revolution” for her birthday. (I was 12, OK?) She later revealed that she didn’t even like the sermon (“He doesn’t quote enough scripture for my taste,” she explained). But because it was a gift from her grandchild, the cassette became the default selection during our weekly trips.

One Sunday, as King reached the crescendo of the “stay woke” speech, my cousins and I began reciting it from memory along with King. “We’re going to win our freedom because both the sacred heritage of our nation and the eternal will of the almighty God are embodied in our echoing demands,” we screeched in King’s same regal sing-song tone. “We shall overcome because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice. We shall overcome because Carlyle is right — no lie can live forever. We shall overcome because Bryant is right — truth, crushed to earth, will rise again.”

I still don’t know who Carlyle and Bryant are (Rick and Kobe, maybe?) but as my grandmother rewound the tape for another round, my cousin elbowed me and whispered a question for which I had no answer, so I asked my grandmother. From my position in the cargo part of the station wagon (which we called the “way-way back”), I yelled to the front: “Aye grandma, what exactly are we gon’ overcome?” The tape whirred. The cabin waited. My grandmother contemplated. Then she twirled both her hands in a flourish that ended in a gesture towards the windshield, saying:

“You know … this.”

Everyone in the car looked out of the window. The land watered with six generations of our family sweat whizzed by. No one said anything, as if every passenger understood her answer. My cousin elbowed me again, but I answered before he could even ask his follow-up question. “I don’t know, either,” I shrugged, twirling my hands as my grandmother did, gesturing like Vannah White at a wheel, a fortune, an entire nation.

“This.”

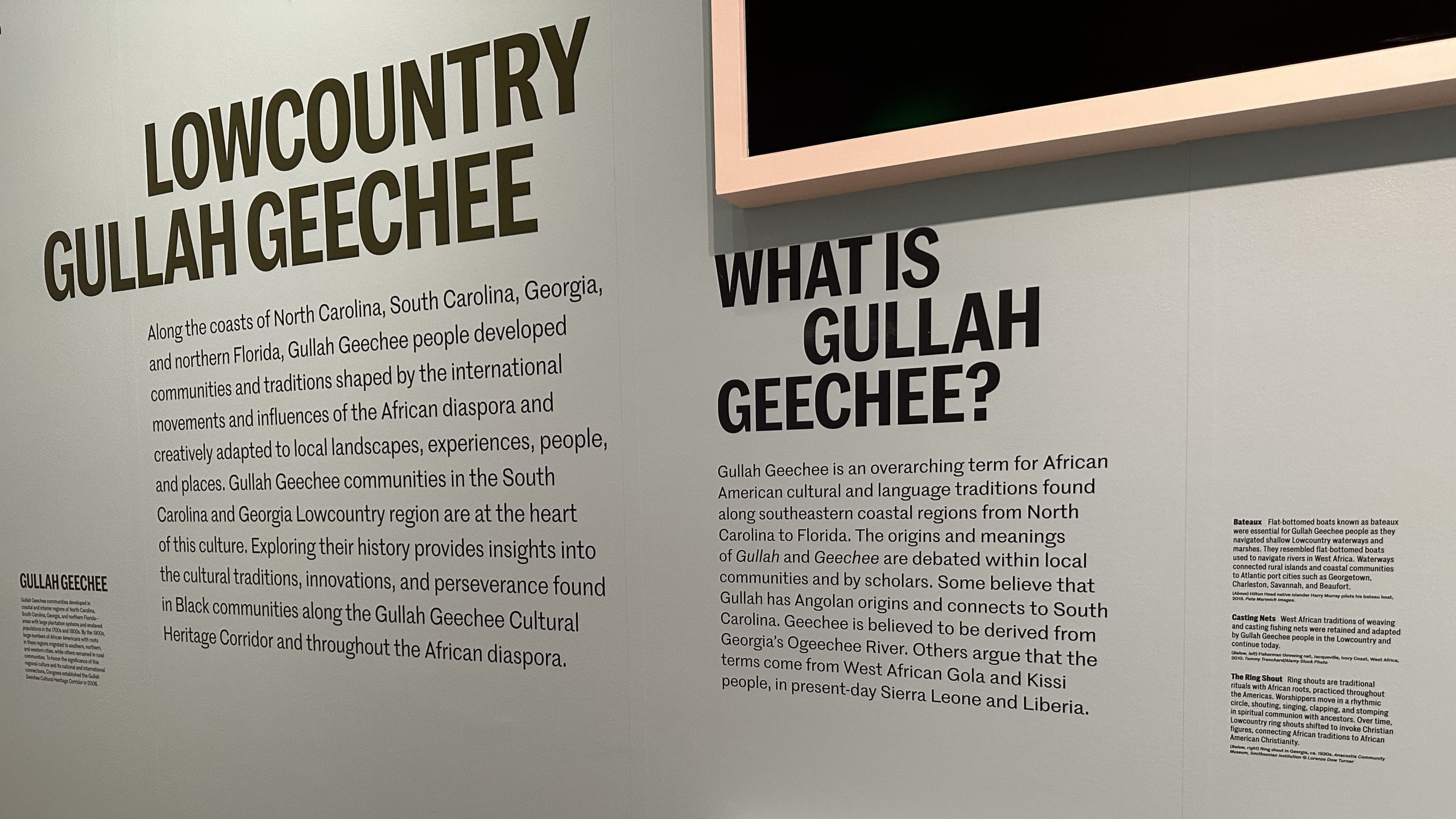

It is important to know what “this” is so the IAAM doesn’t just tell the story of the people who overcame. In lieu of perpetuating a whitewashed, inglorious bastardization of what Black America overcame, it seeks an accurate accounting of a people who resisted, survived and eventually dismantled an international human trafficking system that stole their intellectual labor, work and wealth. You can learn about slaves who came from Africa and the Caribbean in a sixth-grade social studies class. The museum’s Gullah Geechee exhibit tells the Yoruba, Mande, Fula and Bajan origins of one of the world’s rare non-native indigenous cultures. Whitewashed slaves picked cotton but the Carolina Gold exhibit details how African engineers, horticulturalists and inventors — not “slaves” — built an agricultural empire … for free. The IAAM has gathered records from colonial slave ports in Africa and the Americas to house and give visitors access to the largest collection of genealogy records for enslaved people. It is proof that our story was never truly lost to history; it was always intentionally hidden and ignored by … you know … this.

The obstacles that Black America overcame were not random events created by a million monkey gods typing out reality on a million typewriters. Explaining the terrors, theft and violence that America has used against Black people is as historically important as the stories of resistance and survival within its walls. We have to say exactly what we resisted. We must name the things we survived.

To be clear, I am not talking about white people.

There’s a reason why there is no International White American Museum filled with scones, charred crosses and great polka musicians of the past. White museums are just called “museums.” Whiteness is not even a social construct. It is a placeholder for the people who came from a make-believe continent that is, itself, a geographical and social construct. It is a vacuum so empty and devoid of meaning that it is only defined by the absence of the pseudoscientific tropes that it uses as a stepladder. If one drop of not-whiteness can turn a person into something else, then whiteness is nothing. We are something.

Think of all the civilizations, languages and cultures that colonization, empire-building and pure greed have wiped off the face of the earth. With all the privilege with which whiteness has bestowed upon itself, with all of the gold it stole to purchase people it pilfered from the continents it colonized; with all the histories and cultures and people and places and things that whiteness has plundered, erased and genocided into the eternal ether of nevermore, it could not un-Africa the Americas. Not in Ghana or Angola or Jamaica or Haiti or Belize or Barbados or the Bahamas or Brazil or Cuba or Colombia or Costa Rica or the country we watched whiz by us while we sat in the way-way-back.

And for every nanosecond since our toes touched this poached piece of land, they have tried to eliminate what we constructed. But, because they are woefully incapable of doing so, they had to slap together a shoddy, improvised system to reinforce the fragile premise of their supremacy. They made themselves 40% more human in their Constitution and declared our liberty-seekers to be fugitives. They made slave codes and vagrancy laws and one-drop rules and Jim Crow and poll taxes and grandfather clauses and literacy tests and lynch mobs and Klans and slavecatchers and sovereignty commissions and massive resistance and white citizens councils and boys in blue and red lines and white covenants and wars on drugs and segregation academies and lost causes and CRT laws and anti-woke agendas and … you know …

This did not work.

The highlight of the weekend was the invitation-only gala to which I was not invited.

To be fair, it is more correct to say that I was one of many people who were not invited to the official dress-up party for donors, dignitaries and white people. Seriously, nearly every non-Black person I saw during the weekend fell into one of those three categories. So, on the night of the white party for the Black museum, a crew of not-invited guests gathered in a Black-owned restaurant and made our own gala.

Our list of dignitaries included Bakari Sellers, whose father, Cleveland Sellers, was shot by police and imprisoned for leading a civil rights protest and KJ Kearney, the Charleston writer who created the Black Food Fridays food blog celebrating Black cuisine. Also on the not-invited list was the family of Alfred Oko Vanderpuije, who served as principal of a majority-Black high school in Columbia, S.C., before being elected mayor of Accra, Ghana, and eventually representing the region in Ghana’s parliament. Dr. Moses Barrow, the leader of the Belize House of Representative’s opposition party was also there, but you probably know him as Grammy-Award-winning rapper Shyne. My aunt Jannie Harriot founded the state’s Black history apparatus, the African American Heritage Commission, before being booted off to please anti-diversity activists. Of course, she was not invited.

I’d almost forgotten about the white gala until one of the outcasts brought up the letter that another not-invited guest jokingly called “hate mail.” When I realized that we had all received the same disinvitation letter, I offered my services. “Allow me to translate,” I said, surrounded by family members, friends and members of a literal diaspora who shared the same tongue. “Dear negro … Don’tchoo bring yo’ black ass to dese white folks’ gala.”

As everyone laughed, someone behind me tagged the joke. I don’t know who said it, but from my rear, I heard a fellow outcast add: “At least they didn’t use the hard R. See? Progress!”

This is what progress looks like. It is dirty and uncomfortable and funny and maddening and always unfinished. To fully understand the road we’ve traveled, we can’t just pat ourselves for the progress we made. A full understanding of any journey requires knowing where you started from, the route you traveled and why you left in the first place.

The International African American Museum is important precisely because America did not want it to exist. The system they built would not allow it. Whiteness would not let it be. Even if the hands who once held whips were willing and capable, they could not possibly preserve a past they did not respect or know. It showcases a history that we kept alive. When they tried to silence us, we created a language so beautiful that they are still trying to fit it in their mouths. For them, it is a haunted house. Our triumph is that we survived, thrived and built a brand new unkillable culture while we collectively experienced the most intentional system of human subjugation ever manifested into a reality. Not only did we build an African America from scratch, but we did it without human theft or genocide or forced labor or a flag stitched with hate.

But museums are just sheetrock and cement and stories. They are inanimate storytellers. They cannot differentiate between liars and fools. They just warehouse things that already exist. The International African American Museum is a building for the people who were disinvited from the American gala. It is an acknowledgment, not a victory. After all, no lie can live forever. Truth, crushed to the ground, will rise again.

We are the truth.

We are an international African-American museum.

Michael Harriot is a writer, cultural critic and championship-level Spades player. His book, Black AF History: The Unwhitewashed Story of America, will be released in September.

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku, and Android TV. Please download theGrio mobile apps today!