In a few weeks, the D.C. Council will undertake a final vote on legislation that would establish new laws and policies intended to address the rise of homicides and other violent crimes in the nation’s capital.

The Secure D.C. Act, which was unanimously supported by the council in a preliminary vote, seeks to address public safety concerns in Washington, D.C. However, the provisions in the anti-crime bill raise concerns about adverse effects on the sizeable Black population in the district.

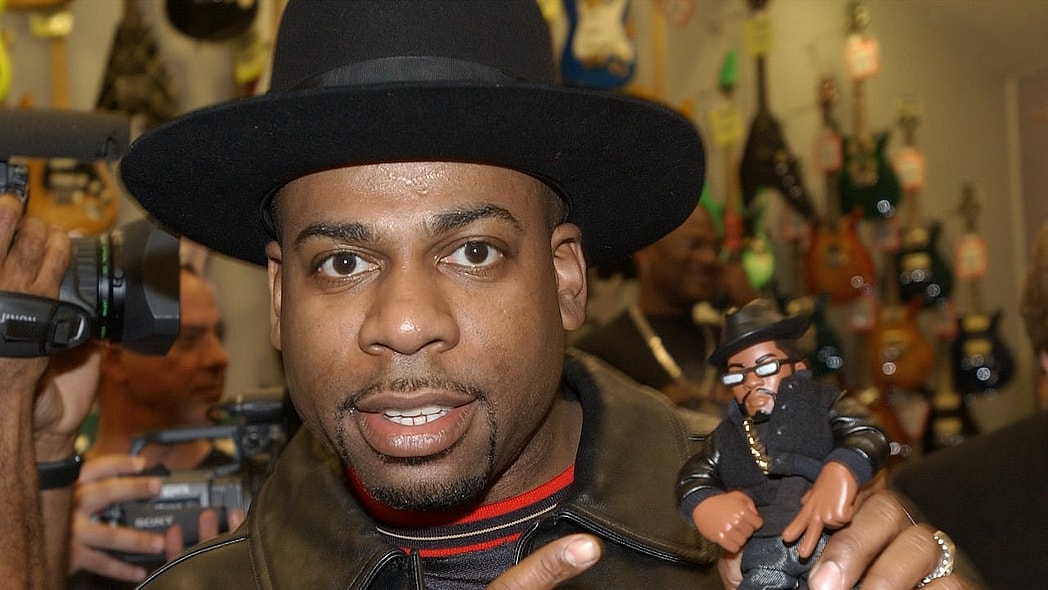

“The Secure D.C. Act, to a very minor degree, makes some investments and adjustments that make it easier for us locally to meet some of the government’s responsibilities, in terms of public safety,” said Markus Batchelor, national political director at People For the American Way and a candidate for the D.C. Council seat representing Ward 8.

He added: “I don’t think overall the Secure D.C. Act is what it’s being billed as.”

The comprehensive public safety omnibus bill contains 100 measures, including provisions that would give the police chief authority to declare “drug-free zones” prohibiting the congregation of two or more people on public property, extend pretrial detention for adults and youth accused of violent crimes, and fine transit passengers who fail to provide their real name and address to issue a notice of infraction.

The legislation also would ban the wearing of face masks to commit a crime or threaten another person, enhance sentencing for crimes committed against elderly and other vulnerable adults, plus expand law enforcement’s ability to engage in vehicle pursuits of a suspect who poses an “imminent threat” to safety.

“I don’t think it effectively addresses the need to hold the guilty accountable,” Batchelor said of the crime bill. “It’s full of pretty dangerous proposals that threaten our civil liberties that unnecessarily put the innocent at risk.”

Washington, D.C., elected leaders, however, have championed the Secure D.C. Act as vital to keeping streets safe.

Mayor Muriel Bowser, who has taken political hits for the district’s crime, urged the 13-member council to “act swiftly” and hold its needed second vote this month.

“We must work with urgency to implement commonsense legislation that will rebalance our public safety ecosystem [and] make our communities safer,” Bowser said in a statement on X.

D.C. Council member Brooke Pinto, who introduced the Secure D.C. Act, said she believes the bill “will help turn the tide on the crime trends that have overwhelmed our communities.”

Pinto said the council is scheduled to vote on the Secure D.C. Act on March 5. However, the bill approved during the first vote may not be the final legislation, as the council could still make additional amendments before passing it into law.

Advocates are hoping there’s enough time to persuade council members to make needed adjustments to avoid causing greater harm to Black residents, who have historically been overpoliced and over-incarcerated.

The Council Office of Racial Equity, an office within the D.C. Council, explained in a report last month that several provisions of the crime bill — such as expanding minimum sentencing for organized retail theft and theft of a car key to steal a nearby vehicle — would “exacerbate” racial inequities for Black residents. The office also said several provisions are “not substantiated by evidence-based research.”

“Further, research shows that several of these provisions are especially harmful to Black residents who are involved, or likely to be involved, with the criminal legal system,” the report reads.

Batchelor, who expressed concerns about the provision to establish drug-free zones, said, “The danger that it poses is that it does really provide a slippery slope for these abuses that we see in these policies all the time when we talk about issues like stop and frisk, when we talk about issues of over-policing in communities of color and communities that are poor.”

The D.C. Council hopeful said the district already has existing laws that allow the police chief and mayor to combat illegal drug activity.

“If we want to enforce the drug laws in our city, we have every capability to do that,” Batchelor contended. “But we don’t need to create new laws to do that.”

The city’s crime issues, he said, are a result of insufficient investments in communities that are driving “the largest gaps in income and wealth, in health outcomes, in life expectancy [and] in joblessness.”

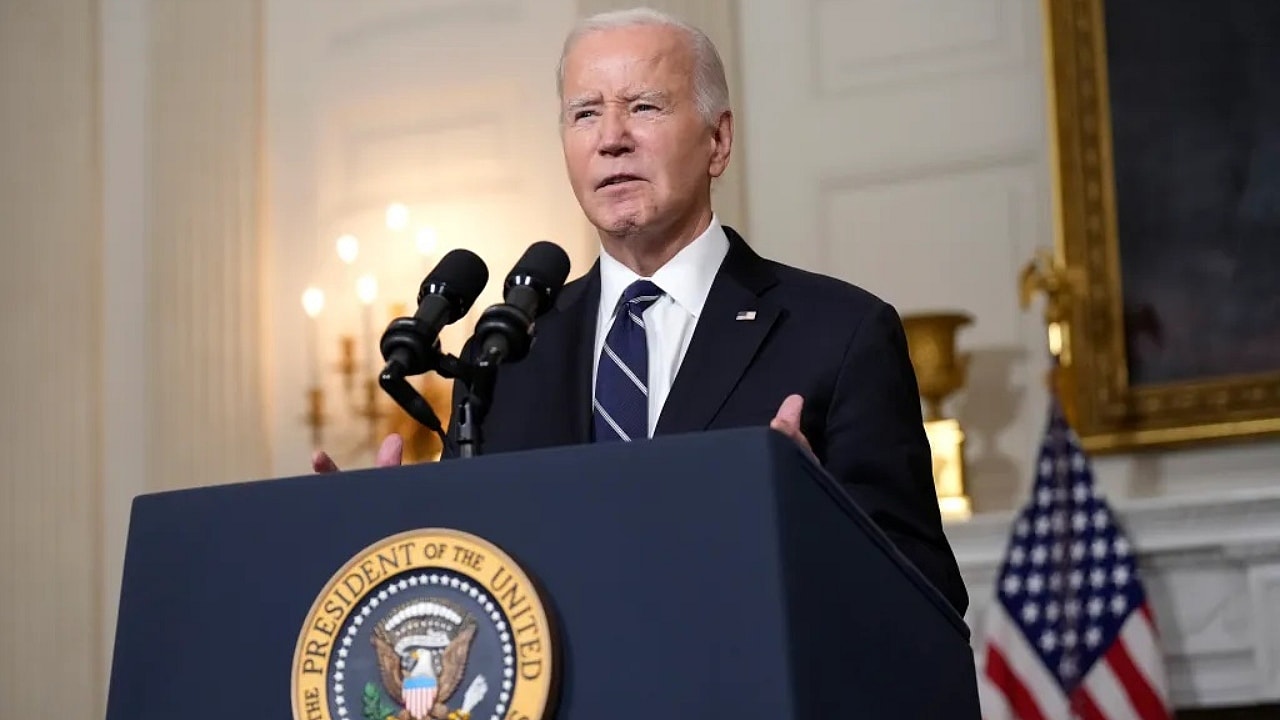

Crime is also a hot-button political issue nationally. As President Joe Biden and national Democrats seek reelection to office this November, they are fighting against accusations from Republicans that their policies are leading to more violence and criminal activity.

Last year, Biden signed a bill pushed by Republicans and supported by some Democrats overturning reforms to the district’s criminal code established by the council – like lowering penalties for carjackings – to the ire of district residents and advocates for statehood.

When asked if the White House had a position on the Secure D.C. Act, press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre told theGrio that while the administration would not comment directly on the proposed legislation, the president “respects D.C.’s right to pass measures that strengthen both public safety and public trust.”

“We’re going to let D.C. go through their process … And we’re going to do everything that we can to continue to lower crime here in the U.S.,” Jean-Pierre noted.

How certain criminal laws intended to end crime and their potentially harmful impacts on Black and brown communities in Washington and elsewhere has been a growing concern for area advocates and progressive policymakers, who have long argued that data shows increased policing and sentencing do not end the existence of crime.

Candice C. Jones, a violence intervention expert who serves as president and CEO of the Public Welfare Foundation, told theGrio that lawmakers should learn from the controversial Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 — best known as the 1994 crime bill — which was signed into law by President Bill Clinton.

“What we see in research is that we are literally still paying, pun intended, for the choices that we make,” said Jones, “and they didn’t make us safer.”

Recommended Stories

The legislation, which was passed 30 years ago, was the largest crime bill enacted in U.S. history, authorizing funding for 100,000 new police officers, $9.7 billion in funding for prisons, and mandated life imprisonment for a third violent felony, also known as the three-strikes rule. Ironically, Biden, then a senator from Delaware, drafted the Senate version of the 1994 crime bill.

“On the basis of that federal legislation, many state and local jurisdictions replicated the things proposed,” said Jones, who said the wave of laws came with a “tenor of getting tougher on crime, increasing penalties [and] increasing incarceration.”

While the criminal measures were intended to end crime, she maintained, “when you look historically, that is not what it has yielded.”

In order for lawmakers and policymakers to truly make a difference in public safety, according to Jones, leaders have to “target communities and people at the highest risk” by offering them something “tangible,” like cognitive behavioral therapy, access to jobs, “deep investments” in education, “supportive services” for youth and young adults and access to small business loans.

“Something that feels like a real incentive to make different life choices than they had,” she explained. “The kinds of investments that we know we put into affluent communities every day to ensure those communities thrive.”

“For a long time,” said Jones, “policymakers haven’t done it in communities of color in a meaningful way.”

Gerren Keith Gaynor is a White House Correspondent and the Managing Editor of Politics at theGrio. He is based in Washington, D.C.

Never miss a beat: Get our daily stories straight to your inbox with theGrio’s newsletter.