Editor’s note: The following article is an op-ed, and the views expressed are the author’s own. Read more opinions on theGrio.

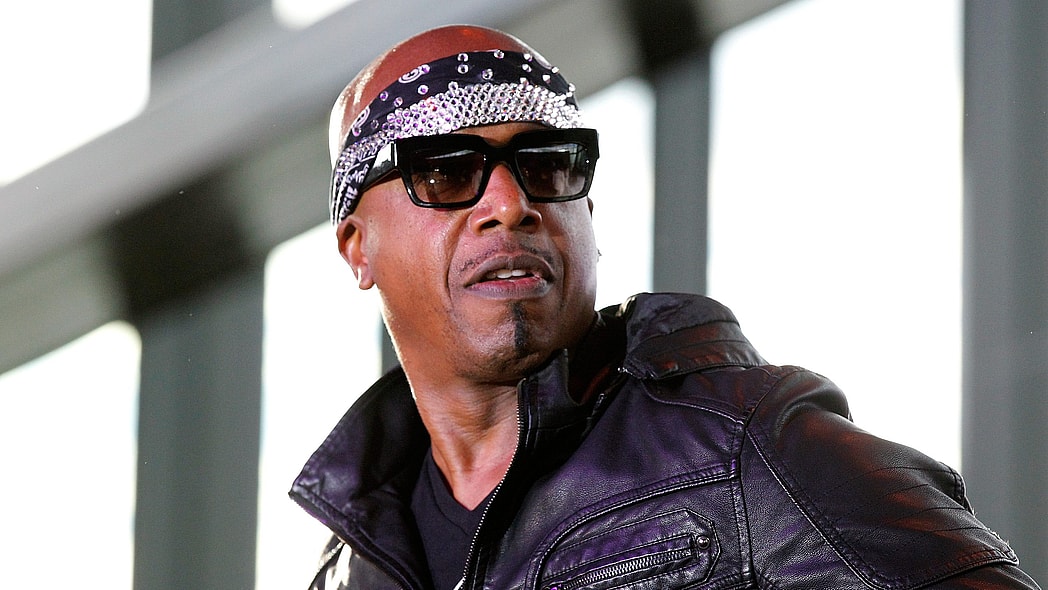

The MC Hammer really is one you had to experience in real time. It’s hard to explain to young people who haven’t heard of him, but Oakland, Calif.’s, MC Hammer (born Stanley Burrell) really was the biggest thing going in hip-hop in the late ’80s. He wasn’t as big as Michael Jackson — who was? — but say, Bobby Brown? Sure. And Bobby Brown was HUGE in the late ’80s but you know who had a Saturday morning cartoon series on a major network? MC Hammer. “Hammerman” may not have been a hit, but it existed.

You know what else was huge back then? “The Simpsons” and Bart Simpson in particular. It was common to find people rocking T-shirts with Bart Simpson doing any number of things from skateboarding to being dressed like Michael Jackson. You know what Bart Simpson T-shirt I had? I had the one with Bart Simpson saying “U Can’t Touch This,” the hook from MC Hammer’s most ubiquitous song, “U Can’t Touch This.” Everybody in 1990 through, hell, the mid-1990s would say, “U Can’t Touch This” as a joke and a nod to MC Hammer. How big of a deal was MC Hammer back then? His album, 1990’s “Please Hammer Don’t Hurt ‘Em” is still one of the best-selling albums in hip-hop history.

My point with all this is that MC Hammer was a thing. In 1990, when “Please Hammer Don’t Hurt ‘Em” came out, I was turning 11 and well, anything that exciting was totally captivating to an 11-year-old. Plus, he was rapping, dancing and looking cool. I had Hammer pants because we all had Hammer pants. When he dropped 1991’s “2 Legit 2 Quit” album (he also dropped the “MC” from his moniker), he was still the coolest dude out. While not as popular as the previous album, “2 Legit…” spawned the single “2 Legit 2 Quit” and had everybody doing this funny hand motion. Though Hammer was a super street dude whose street cred ran super deep in any circle, his musical direction was intended to both uplift and sell records at the same time, and he was very, very successful at it.

And then everything changed. In December 1992, Dr. Dre dropped “The Chronic,” an album that changed, well, everything in hip-hop. Dre. Dre and Death Row Records shifted the center of the hip-hop universe from New York City to Los Angeles, and the sound altered music and the music business for the next four years. While Hammer was a household name in the pop world, hip-hop shifted and the same cool Hammer represented faded as Dr. Dre’s version of gangsta rap — a continuation of the N.W.A. and Ice Cube’s brand of West Coast hip-hop — took hold of the nation. It didn’t help that Hammer took some years off to tend to business-developing groups like Oaktown 3.5.7. So when Hammer decided to release an album in 1994, he looked at the musical landscape and decided to go along to get along. That decision resulted in “The Funky Headhunter,” released on March 1, 1994, an album that sounded way more influenced by Dr. Dre’s G-funk sound than it ever seemed like Hammer would be. Now, the caveat to this is that Hammer was no stranger to Death Row (he eventually signed to the label briefly at the behest of his good friend Tupac). Hammer was friends with Suge Knight years before Death Row was a label. But Hammer’s sound and approach was not the Death Row sound or approach. Hammer’s sound was more unifying, uptempo and uplifting.

Sure, Hammer always talked about the rappers who didn’t want to see any parts of him or his success, but Hammer was pop, through and through. And that wasn’t a bad thing; Hammer was hip-hop the whole family could listen to. Until he both was and wasn’t at the same time.

Recommended Stories

“The Funky Headhunter” isn’t a very good album. The beats are fine, but they all feel like something’s missing, and they more or less highlight Hammer’s limitations as a rapper; when the beat is danceable and Hammer is giving you an anthem to recite, you don’t really care about the rest of the lyrics. When that’s not the case, the songs don’t sound as good. Plus, edgy Hammer felt … off. The entire album felt like he was trying too hard to be (as it turns out accurately perhaps) somebody other than the Hammer we all knew and loved. Perhaps it wouldn’t have mattered; when “The Funky Headhunter” came out, I was 15 and fully entrenched in the West Coast sound and aesthetic. If it didn’t sound “real,” I wasn’t messing with it no matter what coast it came from, especially if it came from the West. And Hammer, because of his previous work, didn’t seem like he was the guy who would rap over the beats talking about the stuff he was talking about. It just felt forced.

And then there was “Pumps and a Bump.” Hammer’s first single from the album (in retrospect, it is also the absolute best record on the album) had a video with Hammer in a leopard speedo, women in bikinis back when that was scandalous and sexually suggestive lyrics, which were a far departure from anything we’d ever heard. Video shows even banned the original video because of Hammer in his speedo, forcing the rapper to reshoot a “cleaner” version of the video. I love the song now more than I did then, though admittedly, without the video to make it a talking point, I think the song would just be another head-scratching song on an already head-scratching album. At least “Pumps and a Bump,” an ode to booty and fine footwear was fun.

I think most people were a bit confused as to what Hammer’s goal was with the album — why would a rapper known for making music that included songs like “Pray,” “Do Not Pass Me By” and “Have You Seen Her?” start trying to sound like a Death Row-extension rapper? Tha Dogg Pound’s Kurupt and Daz even appeared on the album. Fifteen-year-old me was confused and found it easy to move on from Hammer, especially when Snoop Dogg, Tupac and Warren G. were available.

Looking back, the album wasn’t even terrible, not by 1994 standards. It’s not great, and I’m sure even Hammer would do some things differently, but the way it changed the entire narrative of Hammer and rendered him almost obsolete seems a bit unfair. Music consumers are fickle, though, and there have been few artists whose sonic and aesthetic departures were well-received by fans. Hammer would make another 180 with 1995’s “Inside Out,” which took him back towards the sound we all knew and had more gospel-sounding records.

But by then, the Hammer experiment was largely over. He was more famous for his financial troubles; Hammer amassed a huge fortune to the tune of over $30 million a year but had to file for bankruptcy in 1996 due to a huge amount of debt to hundreds of debtors.

At this point, most folks who do remember Hammer relegate a lot of his rap career to some sort of joke, but that’s entirely unfair. Save for the most ardent hip-hop purists and rappers, the rest of us all loved Hammer and clearly we all were getting his albums and songs. Like so many of our landmark artists of the ’90s and 2000s whose falls were public and swift, the punchlines have overtaken the absolute comet-like qualities of their music and careers. I’ll tell you what, while “The Funky Headhunter” isn’t an album I see myself revisiting often, any greatest hits by Hammer is chock full of cookout jams and that is a legacy in and of itself.

And we will always have “Pumps and a Bump,” which will forever be too legit to quit.

Panama Jackson is a columnist at theGrio. He writes very Black things, drinks very brown liquors, and is pretty fly for a light guy. His biggest accomplishment to date coincides with his Blackest accomplishment to date in that he received a phone call from Oprah Winfrey after she read one of his pieces (biggest), but he didn’t answer the phone because the caller ID said: “Unknown” (Blackest).

Make sure you check out the Dear Culture podcast every Thursday on theGrio’s Black Podcast Network, where I’ll be hosting some of the Blackest conversations known to humankind. You might not leave the convo with an afro, but you’ll definitely be looking for your Afro Sheen! Listen to Dear Culture on TheGrio’s app; download it here.

Never miss a beat: Get our daily stories straight to your inbox with theGrio’s newsletter.