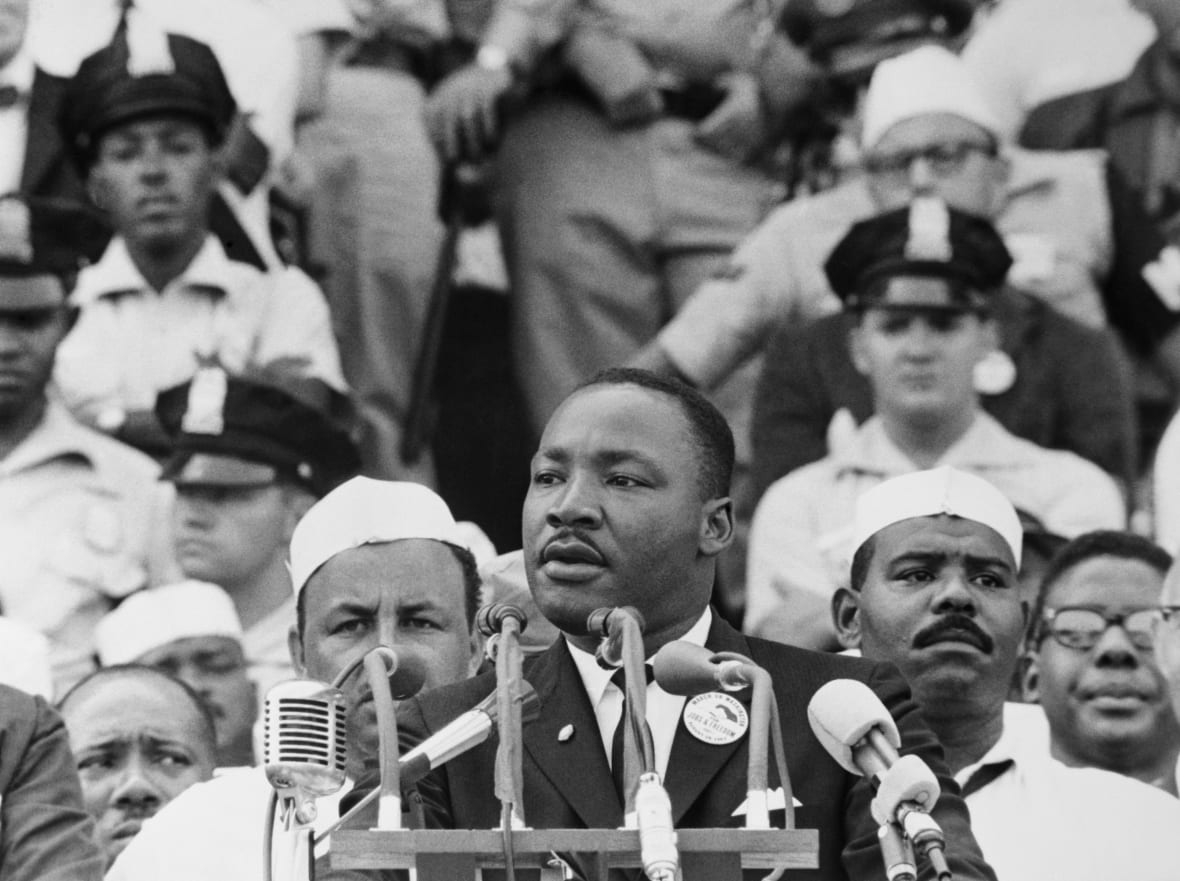

Stevie’s legendary song “Happy Birthday” was originally part of the long, hard battle to turn Dr. King’s birthday into a national holiday. When Dr. King was assassinated, his approval rating with white people was very low. At that point he was not beloved by them. It took a lot of careful, steady, thoughtful, diplomatic work by Coretta Scott King to change his image and win over politicians. Stevie Wonder was committed to that struggle and this song is just one of the things he did for Dr. King. In this ep we talk to King daughter Bernice as well as the engineers who worked with Stevie on the song. We talk about how they got us to having a King holiday and what that fight meant to Stevie. And why he usually records in the middle of the night.

READ FULL TRANSCRIPT BELOW:

Music: Happy Birthday by Stevie Wonder [00:00:06] Happy Birthday to ya! Happy Birthday to ya!

Toure [00:00:09] That is, of course, the proper way to sing Happy Birthday to anyone. And you’ll hear that version at any respectable Black birthday party. But Stevie Wonder‘s 1980 song is about a specific person’s birthday.

Chrissy Greer [00:00:22] But, you know, black people, we love a good song and we love some Stevie Wonder.

Toure [00:00:25] That’s Dr. Chrissy Greer.

Chrissy Greer [00:00:28] An associate professor of political science at Fordham University. I’m also a political analyst at theGrio. Unfortunately, so few Black people of say our generation know the origins of the song, right? The song is just now become at a birthday party. We sing the traditional Happy Birthday, then if you got some Black people at the party, we kick it into the Stevie Wonder version. But I don’t know if a lot of people below, say the Generation X age group know the origins of that song.

Toure [00:00:55] Stevie’s Happy Birthday was a critical part of the decades long battle to get Dr. King’s birthday enshrined as a national holiday. And the song made a difference.

Jelani Cobb [00:01:06] That song was absolutely integral to that holiday being established.

Toure [00:01:12] That’s Jelani Cobb, a writer for The New Yorker and a professor at Columbia.

Jelani Cobb [00:01:17] What happened what Stevie Wonder did, but that song was put him at the front of everyone’s mind. Not only is it a tribute to King, but it is infectous. It’s catchy. I really don’t think that there’s anybody on par. Who could have moved that song uh, moved that struggle for the holiday over the goalpost, over the goal line.

Toure [00:01:37] Stevie cared deeply about making the King holiday into a law. He was close with King’s widow, Coretta Scott King, and he was part of several marches on Washington, pressing the issue.

Stevie Wonder [00:01:48] A world that gives every man, woman and child a respectful job. Absolute peace and sincere and just freedom. I’d like for all you to please join me, urging the U.S. Senate and your senators in particular to vote yes on S100 a bill to make Dr. Martin Luther King Junior’s birthday a national holiday.

Toure [00:02:15] In the liner notes for the album, that Happy Birthday was on 1980s Hotter than July, Stevie wrote, “It is believed that for a man to lay down his life for the love of others is the supreme sacrifice. Jesus Christ, by his own example, showed us that there is no greater love. For nearly 2000 years now, we have been striving to have the strength to follow that example. Martin Luther King was a man who had that strength. I and a growing number of people believe that it is time for our country to adopt legislation that will make January 15th, Martin Luther King’s birthday a national holiday.”

Journalist [00:02:53] Why is this cause so important to you?

Stevie Wonder [00:02:56] In my in my thinking, outside of giving a day to a man who died for the principles of this country, it would be a day for us to reflect upon our responsibility as human beings, as recognizing all of those who have lived and died for the principles of peace and unity and Negro equality for our people.

Toure [00:03:15] Stevie was deeply invested in making Dr. King’s birthday a holiday, and he was an important part of why the years long movement to get the holiday enshrined worked out. Stevie made a nice, sweet pop song that fit with the image of King as the Prince of Peace. But the imperative to have a King holiday grew so deep that as the political battle lingered on, even after the president signed it into law, some people grew angry and offended. And an entirely different song about the King holiday emerged from Public Enemy and Chuck D.

Arsenio Hall [00:03:49] Everybody called Martin Luther King the Prince of Peace. If he saw that video, what do you think he would feel.

Chuck D [00:03:57] He’d a being upset at seeing himself get shot, first of all. And I think.

Toure [00:04:03] And really both Stevie Song and Public Enemies fit with the way we see King today. What corporations and many of our white friends align with is King as nonviolent no matter what. Even when King was physically attacked, he just turn the other cheek. To them, he represents the acceptable way of protesting against racism. This imaginary king is the zenith of the good Negroes. White people like Ronald Reagan capitulated to giving King a holiday almost as a way of saying this is the ideal sort of Black person. Be more like him, nonviolent, colorblind, not scaring us, not making us feel guilty. But if that’s who you think King really is, then you aren’t interacting with the real king. The real king was anti-capitalist, deeply critical of America and extremely pro-Black.

Dr. Martin Luther KIng Jr. [00:05:04] Now, we are dealing with issues that cannot be solved without the nation spending billions of dollars and undergoing a radical redistribution of economic power. Yeah.

Dr. Martin Luther KIng Jr. [00:05:17] That we spend $322,000 for each enemy we kill in Vietnam while we spend in the so-called War on poverty in America. Only about $53 for each person classified as poor. Somebody told a lie One day they couched it in language, they made everything Black, ugly and evil. Look in your Dictionary and see the synonyms of the word black. It’s always something degrading and low and sinister. Look at the word white. It’s always something pure high.

Dr. Martin Luther KIng Jr. [00:06:11] But I want to get the language right tonight. I want to get the language so right that everybody here will cry out “Yes, I’m back. I’m proud of it. I’m black and beautiful.”

Toure [00:06:32] The real King is much more complicated for white America to worship. Also, because of this, even though he was lionized after his life for being nonviolent during his life, his nonviolence was repeatedly met with violence. He was attacked, his supporters were attacked. The FBI spied on him and tried to pressure him. He was murdered. So if King is exemplified for being nonviolent, it’s easy to see. The real message is n*gga, even your nonviolent protests will be met with violence, with threats, with clubs, with wiretaps, with bullets. This is Being Black: The Eighties. I’m Toure. And this is a look at an epic decade through the lens of some of the great songs of the era. Not necessarily the best songs, but the songs that speak best to the issues that shaped the eighties. This time we dive into Dr. King and two very different songs inspired by the battle to make his birthday a national holiday. Stevie Wonder’s song about Dr. King is a lovely tribute that could be played at any family gathering.

Lon Neumann [00:07:40] I don’t have a clear memory of a lot of the details of like who was in the room and what was being said and stuff. But I do have a recollection of of how important it was to Steve.

Toure [00:07:53] That’s Lon Neumann.

Lon Neumann [00:07:55] I am honored to have been part of the team recording Happy Birthday on Hotter than July with Stevie Wonder. Martin Luther King was was gone at that point. And he really that really that was really disturbing for him for for all of us. Really. But him. But more to the point, to him. And so having a national holiday and celebration of Dr. King’s birthday was really important to him.

Gary Adante [00:08:24] I do remember it taking a long time because he wanted to get it perfect.

Toure [00:08:29] That’s Gary, Adante. He was the lead engineer on the song.

Gary Adante [00:08:33] I engineered Stevie Wonder and Happy Birthday. And the whole album Hotter than July, It wasn’t like one session. We recorded it several times in several keys as I remember speeds. We would finish whole tracks sometimes, but then he would ask some random person, you know, What do you think of it? What do you think of the speed? And even if it was somebody who had just walked in and somebody said, you know, I think it could be a little slower or a little faster. We would rerecord it not for the that song, but any song.

Toure [00:09:08] But Gary said with this song, Stevie came into the studio with a clear image of what it should sound like.

Gary Adante [00:09:14] To be fun and obviously happy to sing along and to make it sort of a joyous thing. I knew that he had a vision and you told me that about that Martin Luther King Day would be a holiday and he was going to make it happen. He had this inner vision happening. He saw it as a holiday and that he was driven by that.

Toure [00:09:43] The song is one of the key salvos in trying to make King’s birthday into a holiday.

Lon Neumann [00:09:48] There’s not a lot that an entertainer can do to change the course of history, but this was something that he could do, was to champion the birthday as a holiday. So it was important to him to be able to do that because he can really organize rallies and galvanize people and movements. But he did, I mean, in his own way and he does in his own way, But that was his way of doing it.

Toure [00:10:16] The chorus is easily transportable to any party, but the verses are Stevie making the case for the King holiday.

Music: Happy Birthday by Stevie Wonder [00:10:24] I just never understood, how a man who died for good, could not have a day that would, be set aside for his recognition.

Gary Adante [00:10:41] He lays it out in lyrics. He says, I can understand why this doesn’t exist. Then what? What’s what’s wrong with people? Why? Why doesn’t it already exist? So he doesn’t really pull punches in the lyrics. He just really lays it out.

Toure [00:10:55] Stevie’s syrupy sweet song struck the right political tone to help the King holiday bill get over the hump. Sometimes in the struggle for black justice, people feel like they have to ask nicely. The song fits that vibe and helped the cause. But it was quite a battle to make the holiday a law. It took over a decade of perseverance to get the King holiday through Congress and to the president’s desk. It was first proposed in the late sixties. It was championed in the seventies by Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm and pushed even more in the early eighties.

Jelani Cobb [00:11:29] John Conyers introduced the bill to make King’s birthday a holiday the week that he was assassinated. And so that started from 1968. So by the time we got to the 1980s, you know, there were people who had been in the trenches for a dozen years trying to get this law passed and ratify and, you know, to ratchet up the pressure on the Reagan administration. And so I think that the dynamic that went into King getting a holiday, partly social and cultural in terms of, you know, white people finding him palatable, finding King palatable. But also, you know, because of the extraordinary effort that had been put into it for such a long time.

Toure [00:12:14] President Ronald Reagan initially opposed a King holiday, but then Congressman Harold Washington, who would later become the mayor of Chicago, led Illinois to adopt a King holiday.

Harold Washington [00:12:25] In recognizing Dr. King, this country would do itself honor both here at home and abroad by telling everyone that black people have been an integral part of this country and world. We’ve made our contribution, notwithstanding adverse circumstances. And symbolic of that great people we want to recognize in a national holiday. The one and only the late Dr. Martin Luther King Junior. Nothing short of that will do.

Toure [00:12:54] After Illinois adopted it, many other states passed legislation to recognize it. Thanks to an increase in Black political power in the eighties.

Jelani Cobb [00:13:03] There was this wave of Black mayors who were coming into power, coming into office.

Toure [00:13:09] In the eighties, you had Black mayors in Camden, Little Rock, Chicago, Memphis, Flint, Philadelphia, Baltimore, New York City.

Jelani Cobb [00:13:17] And these largely Black city councils. And so as we’ve built this movement for a King holiday was picking up momentum was the exact point where there were figures who were sympathetic to it, who were increasingly taking the helm of these cities, and certainly in Democratic controlled states, it came to be seen as the moderate, modern kind of thing to do. But, you know. KING If anybody deserved the holiday, King did. And, you know, that was, I think, the way that it developed and grew and generated momentum.

Toure [00:13:50] And we can’t tell the story of how the King holiday came to be without the incredible decades long efforts of his widow, Coretta Scott King.

Dr. Bernice King [00:14:01] Making of this holiday ad It really was when my mother focused her attention around it that things started to kind of take off a little bit more.

Toure [00:14:10] That’s Dr. Bernice King, daughter of Coretta and Martin.

Dr. Bernice King [00:14:14] CEO of the King Center and a legacy bearer for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. And Mrs. Coretta Scott King. She spent the majority of the time from 68 to about 79, really trying to put in the necessary work of getting the King Center off the ground and the headquarters built. And so in 79, when she really turned all of her attention towards the King holiday and did lobbying in 79, she went and testified before Congress in 1980. She also was sending out letters to state legislators and governors and mayors asking them to recognize and celebrate the birthday. The most important part is she built a groundswell from the local and state level to the federal level.

Toure [00:14:59] It was a bottom up movement that got the King holiday recognized and celebrated in cities and states across the country before the federal government officially recognized it, because that put pressure on the federal government.

Dr. Bernice King [00:15:12] It’s a strategy that my mother understood. Let me get the buy in of the local and the state. So we literally have ordinances and proclamations from cities and states across the nation. Because she wrote letters in the seventies to all of the states and cities to recognize Dr. King’s birthday, to celebrate it as a birthday.

Toure [00:15:39] She knew just how to speak to legislators to get her message across.

Dr. Bernice King [00:15:43] She worked in back rooms. I mean, my mother knew how to work alone. She knew how to work people she knew across aisles. She knew how to speak in such a way to people, to get them to listen, at least say with the hard change, but at least listen. And I think she was able to convince people, you know, that is okay, is saying this is going to benefit the nation. You know, I think the way it was presented to her from her angle, it wasn’t about a black holiday. It was about a holiday of a man who represented so much to what we are as citizens of the world first and as as citizens of the United States of America and our democracy. And what all of our founding documents at least met on paper. And so she knew what language to use with them. My mother was determined she was going to stop, period. And she believed that she had the ability to win people over.

Reverend Dr. Barbara Reynolds [00:16:36] Well, let’s put it that way. If we rule her out, there, probably would not be a King holiday.

Toure [00:16:43] That’s Reverend Dr. Barbara Reynolds, who worked with Mrs. King on her memoir, Coretta My Life, My Love, My Legacy.

Reverend Dr. Barbara Reynolds [00:16:50] She had to personally call on every Senator in the Senate personally. At least tried to all who would receive her. She had to get people like Stevie Wonder. What she had to do was formalize it. And this was something they said was unheard of.

Toure [00:17:09] She did the grassroots work and played the D.C. game and helped reshape King’s image so that white lawmakers could feel comfortable voting for a King holiday. It’s hard to imagine it now, but toward the end of King’s life, the vast majority of white Americans disliked him. A 1968 opinion poll found King had a 75% disapproval rating. They thought he was dangerous and divisive. Coretta helped change how people saw King as part of her lifelong commitment to him and to the movement.

Reverend Dr. Barbara Reynolds [00:17:44] In the middle of the Montgomery bus boycott, she was in the room with a shuttle and the bottom of the front of the porch. And that X that Dr. King’s father came and said, to her “You going to have to leave Montgomery because it’s too dangerous” and she said, “You just think I’m married to Martin But I’m married to the movement.”

Toure [00:18:12] With Coretta applying delicate pressure and Stevie’s song galvanizing interest and the Republican Party not wanting to appear racist. Imagine that Reagan felt boxed into a political corner as lots of cities and states adopted the King holiday.

Jelani Cobb [00:18:28] If it was one thing to oppose the law, it’s another thing to be willing to veto it. And given Reagan’s already tepid position on South Africa and the fact that the Republican Party had been tainted with these allegations of racism back in the time when they actually cared about that, that the party had been tainted with these allegations of racism. They were not going to stop the bill if it got to the president’s desk. And once it had generated that much momentum, literally coming up from grassroots movements and statewide movements across the country. It was very much difficult to stop.

Toure [00:19:02] Reagan signed it into law in 1983, but at a press conference that year, he showed how shallow his support for the holiday really was.

Journalist [00:19:11] President Senator Helms has been saying on the Senate floor that Martin Luther King Jr had communist associations, was a communist sympathizer. Do you agree?

President Ronald Reagan [00:19:22] We’ll know in about 35 years, won’t we?

Toure [00:19:25] He’s referring to sealed records about King that would not be open for 35 years. But is this what a president should be saying about King right after turning his birthday into a holiday? Maybe he was a communist. We can’t be sure. Wink, wink. This is what people used to call dog whistling. You’d say something that was semi vague, that signaled something to your political side without overtly saying it. So people of your political mindset heard what you really meant, but you hadn’t really said anything. So if someone tried to call you out, there was plausible deniability. I mean, Reagan didn’t say King was a communist. He said he didn’t know if he was a communist. But all that ain’t even necessary when it’s clear that King was an anti-capitalist who was in favor of reparations.

Dr. Martin Luther KIng Jr. [00:20:15] Through an act of Congress, our government was giving away millions of acres of land and the West and the Midwest. Which meant that it was willing to undergird its white peasants from Europe with an economic flaw. But not only did they give the land. They built land grant colleges with government money to teach them how to farm. Not only that, they provided county agents to further their expertise in farming. Not only that, they provided low interest rates in order that they could mechanize our farm. Not only that. Today, many of these people are receiving millions of dollars in federal subsidies not too farm. And they are the very people telling the Black man that he ought to lift himself by his own bootstraps. This is what we are faced with and this is the reality now when we come to Washington in this campaign. We are coming to get our check.

Toure [00:21:22] Amen.

Jelani Cobb [00:21:23] King points out in more than one speech, actually, in the aftermath of slavery, when the Homestead Act is passed and all of that land is given to American families, Black people are, by and large, excluded. And so not only does the former slave population have to deal with the exploitation that happened during the years of bondage, they miss out on the economic boom in which the federal government is literally giving away land. And so he talks about the context of reparations. And the other thing that he talks about is the universal basic income. Saying, that we have the means to eradicate poverty in the United States. And we should have a universal basic income, a point that no one will fall beneath on the economic ladder. And so all these positive emerging tools that, you know, are not consistent with the very narrow way that we understand him. King, I think was very much aware of the shortcomings of capitalism and the connections between capitalism and the exploitation of Black people and the exploitation of poor people more broadly. And so that was in the course of the Cold War. That was enough. Anything short of absolute fanatical of flag waving adherence to capitalism was enough to get you declared to be, you know, a socialist.

Toure [00:22:50] This is not the King we’re talking about each January. Just like Christmas is about presence and materialism and not about Jesus. The January King holiday is about America’s Gandhi colorblindness and having a dream about a post racism society. It’s not about King’s ideas, about a society that’s more just for poor people.

Jelani Cobb [00:23:13] King critiques capitalism and what capitalism has done and the materialism that capitalism is, and the vast disparities between the wealthy and the poor, which go straight to the core of the social structure of the United States. You know that King is not the one that we see most of the time talked about in January, not the one that we see, you know, corporations endorsing and trying to position themselves as being part of his vision.

Toure [00:23:41] And yes, we got a King holiday in the eighties as a powerful step forward, acknowledging the importance of a Black man and his values. But the nation did nothing to address his values. Did Reagan attack poverty as King would have wanted?

Toure [00:23:56] Not at all.

Toure [00:23:57] Black poverty expanded in the eighties. A major step back. Again, black history is one step forward, one step back. And the step forward of getting the King holiday enshrined in law was deeply important to a lot of people. It was like a victory for all of us. But that victory was also undercut because a few states dragged their heels like petulant children. The biggest offender was Arizona. Now a word from our sponsors.

Toure [00:24:27] First, the Governor Dean, recognized the holiday in the state. I didn’t even know that was a thing. Then there was considerable back and forth in the state legislature. Many supported re recognizing the holiday and they tried to get it passed, but nothing could get the legislation over the hump. As Arizona dithered, the state lost millions and millions in dollars from tourists. And yet, when two referendums were put to Arizona voters in 1990, giving them two options of making the King holiday a law, the voters rejected both. This infuriated a lot of Black people. We had finally gotten the day for our king, and Arizona was like, Fuck him.

Chuck D [00:25:11] You know, because right now I looked at it as being a slap in the face.

Toure [00:25:14] That’s Chuck D.

Chuck D [00:25:15] You got one state that says, you know, forget Martin Luther King, I don’t care how you’re feeling. And to me, you know, like people will wise, intelligent people, and we should be given credit where credit is due.

Hank Shocklee [00:25:28] It was like, wait a minute, hold up.

Toure [00:25:31] That’s Hank Shocklee, the lead producer for Public Enemy.

Hank Shocklee [00:25:35] This is a holiday and it’s not national and so the idea was to agitate that process and bring an awareness to it, because you have to remember back then it was no Black news.

Toure [00:25:49] Chuck D loved to say rap was Black America’s CNN but really, Public Enemy itself fulfilled the mission of publicizing political issues in the community.

Hank Shocklee [00:25:59] And the idea of Public Enemy was to want to bridge the gap between what we see and what we hear in the community and what we was putting out to the rest of society so that they can feel the same energy that we was feeling.

Toure [00:26:13] That’s when Public Enemy entered the chat with all the subtlety of a Mack Truck.

Music: By the Time I Get to Arizona by Public Enemy [00:26:20] This is Sista Souljah. Public Enemy, security of the First World and all allied forces are traveling west to head off a white supremacist scheme to destroy the national celebration of Dr. Martin Luther King’s birthday. Public Enemy believes that the powers that be in the state of New Hampshire and Arizona have found psychological discomfort in paying tribute to a Black man who tried to teach white people the meaning of civilization. Good luck, brothers. Show em what you got.

Toure [00:26:49] PE’s Song about the King holiday starts with abrasive, aggressive, bad ass noise.

Hank Shocklee [00:26:55] PE was all about pushing you.

Hank Shocklee [00:26:57] It was all about agitating. It wasn’t about making you feel comfortable, making you feel good in your own space about issues, because I don’t think that that was that’s productive. I think what was productive is something that that physically move you. And so the sound to me has to represent that vibration.

Toure [00:27:17] It’s white noise from a synthesizer that recalls the sound of chaos. They were one of the first mainstream artists who played with noise in that way. They wanted you to be able to see the music.

Hank Shocklee [00:27:30] You think about all the Public Enemy records. The idea is to create a visual context for you because, you know, I’m from the School of Visual Art, and everything to me has to have some sort of visual approach to it. Chuck is the same way. Chuck is a graphic artist and a mechanical drawer. So we kind of like that’s how we click. And so when you think about the sound, it’s all about what the sound makes you feel like, as opposed to what the sound actually is. The sound is not going to give you what the idea in the sense of the song is about. It’s going to give you the feeling and the emotion of what the song is about. And that’s the idea that when we go in, so that when you’re listening to it, you’re not listening to it on a point of one or two dimensional plane, you’re listening to it on a three dimensional plane.

Toure [00:28:22] And then the song adds a church choir ooing.

Music: By the Time I Get to Arizona by Public Enemy [00:28:27] Pray. I pray to I do and praise Jah the maker, Lookin for culture I got but not here from Jamaica, Pushin and shakin’ a structure, bring it down to Babylon Hearin the sucker that make it hard for the Brown.

Toure [00:28:38] It’s like let the church say amen to this preacher who’s about to rock the mic. Or it’s like there’s this Greek chorus standing by watching this madness that Chuck is about to go in on, Shocklee said, it’s a reference to how during the Civil Rights Movement, the church had been part of planning and organizing the movement.

Hank Shocklee [00:28:58] The church was was not just a place where we go in worship. It was a battle station. It was a place that we formulate ideas. We, we, we we strategize on what our next mission was going to be.

Toure [00:29:13] When Chuck comes into the song, you know, he’s angry as hell, but he’s much more in control than angry, Ice Cube on Dope Man. Chuck isn’t a young man who’s warring at the world. He’s a political thinker who’s fed up with the political system, rejecting both the Dems and the Republicans.

Music: By the Time I Get to Arizona by Public Enemy [00:29:31] Neither party is mine not the Jackass or the Elephant.

Toure [00:29:35] Which is why he’s taken matters into his own hands. And he says all of Arizona deserves his ire.

Music: By the Time I Get to Arizona by Public Enemy [00:29:42] What’s a smiley face when the whole state’s racist?

Toure [00:29:45] He’s saying racism isn’t about interpersonal relations. It’s not about being nice to people smiling at people. It’s about systems of injustice. So you can smile and be nice to me while perpetuating racism. That’s what Chuck’s seeing. And after two votes rejecting the King holiday he’s done with Arizona.

Music: By the Time I Get to Arizona by Public Enemy [00:30:07] I urinated on the state, while I was kickin’ this song.

Toure [00:30:11] It all goes to another level with the music video. It aired on MTV like twice because it was so controversial. But now you can youtube it any time you want. It’s scenes of a King character leading nonviolent marches in sit ins and being attacked by restaurant workers and ultimately being dropped by an assassin’s bullet. This narrative is intercut with scenes of Chuck and his crew, the S1 Ws planning and then carrying out a violent attack on the leadership of Arizona. Some politicians get shot. One gets poisoned and one gets blown up by a bomb while sitting in his limo after Chuck pushes the button to detonate it. Chuck called the video a revenge fantasy.

Chuck D [00:30:55] And basically the violence was a was a a slap in the face of the American system that’s been violent to us for, what, four hundred, five hundred years?

Toure [00:31:04] Shocklee said they always wanted their videos to be so powerful they could end up getting banned.

Hank Shocklee [00:31:10] The first video, which The Black Steel. It started there.

Toure [00:31:13] Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos.

Hank Shocklee [00:31:16] And since we got banned from there, the whole idea of, okay, well then fuck it, let’s just make more, more, more videos that get banned because, you know, there’s a there’s a certain emotion that happens when people dislike something, because I believe that hate is just as strong as emotion of love. So if you don’t like something, you’re going to speak strongly about it. And if you love something, you’ve got to speak strongly about it. So now the idea is how can you create all those emotions converging at the same time? And that’s the that to me is the idea of what to do.

Toure [00:31:54] A lot of white people got mad about it, but they didn’t deal with the fact that PE was pointing out how the nonviolence of King was met with violence. So a white critique of black political violence rings hollow. They didn’t deal with the idea that if nonviolence means being attacked and murdered and not getting political success, then why be nonviolent? Chuck D went on Nightline in 1992 when it was one of the most watched shows in the country, and his video was one of the most controversial pieces of art in the country. And, well, this happened.

Chuck D [00:32:30] The purpose of rap music or any kind of music, I feel, is to raise dialog. And the reason I raise dialog on this particular issue, because me as a Black person has been tired of being dissed, disrespected, especially last year when the Bush administration kind of like went into the Persian Gulf on January 15th. That’s when they encouraged me to write the song.

Journalist [00:32:53] Wait wait you’re getting awful far along for me here. I thought you wrote the song because you were upset about Arizona not making the Martin Luther King birthday a holiday, and you thought you’d make a very strong point.

Chuck D [00:33:03] Well it was acombination. I mean, not having a King holiday in Arizona. And at the same time, going into the Persian Gulf, going into a war, a nonviolent person at the same time, Arizona not having this holiday spurred me to write that song.

Journalist [00:33:18] Well, it would seem in the minds of a lot of people, a bit of a stretch to go from there to to blowing away the governor of Arizona and some state officials.

Chuck D [00:33:26] Well, basically, I think this would be a fair place in America. But, you know, you have to realize in the video, we set a scenario which can happen in the next two or three years of a David Duke type character going to win the governorship or all of the fictional characters in Arizona, corrupt officials, part of other organizations saying, no, we will not have a King holiday. Basically also pointing out that there has been so much hypocrisy and a big conspiracy against every single Black leader that has come out violent or nonviolent or whatever they want to call it. Matter of fact, in the video, I’m making the statement against various things. The holiday that we celebrate in America, the 500 years of genocide on Columbus Day, and yet still we got to have a state that’s not going to have a King holiday. That’s ridiculous.

Toure [00:34:16] At their heyday in the eighties. Chuck was the political activist that hip hop needed. There was no one in popular music better than PE at making powerful, in-your-face political songs, the sort of music Malcolm X would have made if he were alive in the eighties, where Stevie was like the son of the civil rights movement with an insistence on acceptance and nonviolence. Public Enemy was the son of the Black Power movement. They were going to get it done by any means necessary. In these two songs, Happy Birthday, and By the Time I Get to Arizona, Stevie and Chuck D represent two sides of the Black liberation struggle. The supposedly good nonviolent protester who’s politely asking for justice based on a moral appeal and the aggressive, unapologetic protester demanding Black rights right now, who’s willing to be violent if that’s what’s needed?

Malcolm X [00:35:10] Historically, revolutions are bloody.

Toure [00:35:13] That’s Malcolm X.

Malcolm X [00:35:15] Oh, yes, they are. They have never had a bloodless revolution. Or a nonviolent revolution. It don’t happen even in Hollywood. You don’t have a revolution in which you love your enemy and you don’t have a revolution in which you are begging the system of exploitation to integrate you into it. Revolutions overturn systems. Revolutions destroy systems. A revolution is bloody. But America is in a unique position. She’s the only country in history in a position actually, to become involved in a bloodless revolution. All, she’s got to do is give the Black man in this country everything that’s due him. Everything.

Toure [00:36:10] Can the Black protester who’s willing to be violent, truly be said to be violent. If someone is beating you up and you fight back. Are you being violent? No. You’re defending yourself. Well, after centuries of violence being visited on Black America is violence in the name of the fight to get justice for Black people. Is that actually violence or is it self-defense? We’ve had centuries of slavery and domestic terrorism by white civilians like lynchings and white mobs burning Black towns like Tulsa and Rosewood, and political assassinations and state sanctioned violence by police and the economic violence? And how many times do Black people have to be punched in the face before fighting back is considered self-defense in a world where violence upon Black people is constant. And nonviolence may not work to demand that we be nonviolent when we protest is offensive. And is it effective? Will white supremacy lift its boot from our neck? If we ask nicely and say please and don’t raise our voice? No, it won’t. As Frederick Douglass said, “Power concedes nothing without a demand. Find out just what any people will quietly submit to. And you have found out the exact measure of injustice and wrong which will be imposed upon them. And these will continue until they are resisted with either words or blows.” Wow. For a revolution to truly change society. It often requires violence because a real revolution needs the power system to be afraid of continuing the status quo. The dichotomy of nonviolent versus violent is a false one. When getting real change requires both methods. The eighties stands out for an absence of towering black leaders fighting on behalf of the community. Where the Sixties had King and Malcolm X and the Black Panthers. And recent years saw the rise of Black Lives Matter. The Eighties lacks those epic prophetic activists, kings and queens. As we continued to combat some of the same issues that King and Malcolm spoke about. We look to them as models of how to fight, which is part of why the image of King was so important. The enshrinement of the King Holiday confirmed that he was a crucial American and in a way, having a holiday celebrating the birthday of a Black hero signaled that we were crucial Americans, which is why it was so important to win that political battle and why it was so infuriating when some refused to recognize King. Well, long before the King holiday, we already had a holiday celebrating the birthday of a global Black hero. But some people still don’t realize that Jesus was Black.

The Brady Bunch [00:39:02] Sure, Jan.

Toure [00:39:03] While eighties Black America luxuriated in the glory of a King holiday. We also battled a monsoon of trauma because black history, as we’ve said before, is always one step forward, one step back. In the eighties, the war on drugs was launched and that led to a steep rise in the number of Black people who were incarcerated. And that had a devastating impact on Black America.

[00:39:36] I’m Toure and this was Being Black: The Eighties. The next episode of this show is already available and soon we’ll be back with Being Black: The Seventies. This podcast was produced by me, Toure and Jesse Cannon and scored by Will Brooks with additional production by Brian de Meglio and executive production from Regina Griffin. Thank you for listening to this podcast from theGrio Black Podcast Network. Please tell a friend and check out the other shows on theGrio Black Podcast Network, including Blackest Questions with Chrissy Grier, Dear Culture with Panama Jackson, The Grio Daily with Michael Harriot and Writing Black with Maiysha Kai.